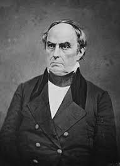

Daniel Webster: Famous American Lawyer, Orator, Politician

Part 2: Later Days

A supporter of a strong federal government, Webster favored the American System policies of the newly created Whig Party, of which he became a member. Webster also supported President Andrew Jackson's handling of the Nullification Crisis. However, Webster and Jackson were on opposite sides of the debate over the Second Bank of the United States. It was Webster, along with Henry Clay, who convinced then-Bank President Nicholas Biddle to apply for an early renewal of the Bank charter that ended up in Jackson's veto and the slow demise of the Bank. Webster also opposed Jackson's implementation of the "spoils system" and his harsh treatment of Native Americans; in particular, Webster opposed the Indian Removal Act of 1830. One of Webster's long-sought-after goals was becoming President. He ran for the office in 1836, as part of the Whig Party's regional strategy to defeat incumbent Martin van Buren; the strategy did not work, and van Buren was re-elected. Webster again sought the nomination in 1840; this time, the Whigs picked only one candidate, William Henry Harrison, who won the election. Harrison named Webster to be Secretary of State. When Harrison died just days after taking office, Vice-president John Tyler assumed the presidency. Webster did not agree with Tyler's actions at the time. Neither did the two men get along; Webster resigned as Secretary of State in 1843 and returned to the Senate two years later. One of his accomplishments while heading up the State Department was the negotiation of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, which eased tensions with Great Britain over the Maine-New Brunswick border. he also oversaw the writing of the first treaty between the U.S. and China. Continuing in his quest for the presidency, Webster again sought the Whig nomination, in 1844 and in 1848. The Whig standard-bearers in those elections were Clay, who lost to James K. Polk in 1844, and Zachary Taylor, who won in 1848. Webster had long opposed the spread of slavery that extended to opposition to the annexation of Texas and to war with Mexico. He supported Clay's Compromise of 1850, however, even though it included the Fugitive Slave Act that angered his constituent, because he thought the preservation of the Union of paramount importance. He reasserted his beliefs on the matter in a famous address known as the Seventh of March Speech. Also in 1850, President Millard Fillmore appointed Webster Secretary of State. Webster's last hurrah in politics was one more attempt to win the Whig presidential nomination. The party in 1852 chose Mexican American-War hero Winfield Scott instead, and Webster refused to work to help get Scott elected. (Elected president in that year was Franklin Pierce.) Webster died on Oct. 24, 1852. He is remembered for his oratory skills and for his legal acumen. He had married Grace Fletcher in 1808, and they had five children, two of whom died before reaching adulthood. Grace herself died in 1828. Webster married Caroline LeRoy in 1829; she survived him. Webster and his first wife and children lived in Portsmouth until 1816, then moved to Boston. Webster and his second wife moved to a large estate in Marshfield, Mass., in 1831. Some of Daniel Webster's famous sayings:

Next page > Later Days > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

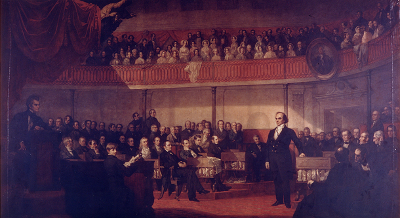

He engaged in a serious of high-profile debates on political matters, in and out of Congress. One such debate occurred in January 1830 on the floor of the Senate. Webster and South Carolina Robert Hayne and famously debated the supremacy of the federal government in relation to state governments. The most famous of these speeches, Webster's Second Reply to Hayne, contained a reminder that the ultimate power of the government was in the hands of the people, who had established the Constitution that formed the government and who had elected the members of that government. Strongly voicing his opposition to states' having more power than the federal government, he ended his speech with the famous words "Liberty and Union, now and for ever, one and inseparable!"

He engaged in a serious of high-profile debates on political matters, in and out of Congress. One such debate occurred in January 1830 on the floor of the Senate. Webster and South Carolina Robert Hayne and famously debated the supremacy of the federal government in relation to state governments. The most famous of these speeches, Webster's Second Reply to Hayne, contained a reminder that the ultimate power of the government was in the hands of the people, who had established the Constitution that formed the government and who had elected the members of that government. Strongly voicing his opposition to states' having more power than the federal government, he ended his speech with the famous words "Liberty and Union, now and for ever, one and inseparable!" "Every unpunished murder takes away something from the security of every man's life."

"Every unpunished murder takes away something from the security of every man's life."