The American System: Blueprint for Expansion

The American System was a three-part development plan that emphasized the federal government's role in the economy. The plan had its zenith in the first part of the 19th Century.

The American System was the brainchild of noted lawmaker Henry Clay and was based on the ideas of Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and the architect of much of the country's economic system. Clay was the driving force behind the American System; other proponents were John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, and Daniel Webster. The three legs of the American System tripod were these:

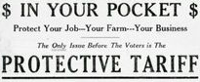

For the first few decades of the country's existence, the majority of its citizens were farmers. The 13 Colonies did have businesses, some of them big, but imports of manufactured goods still exceeded exports. Once the countryside was secure after the end of the War of 1812, Americans were free to continue pursuit of internal improvements. The lawmakers most wanting to implement the American System were members of the Whig Party. This party had a significant membership in Congress and was able to pass bills to address two parts of the three-pronged strategy: a tariff bill and a bank bill. Congress in 1816 created, and President James Madison signed, a bill creating the Second Bank of the United States and a bill creating the Tariff of 1816, which implemented a tariff of from 20 to 25 percent on all foreign goods. The idea behind a tariff on imports was to stimulate American manufacturing, so as to enable it to catch up to the outputs of other countries, such as Great Britain, still America's largest trading partner. Placing a tariff, or tax, on imported goods would make them more expensive and, so the theory went, less attractive to Americans looking to buy such things. As well, building up the industry within the country would help insulate the economy from difficulties abroad. Tariffs were a favored part of American economic policy for nearly two decades, until fierce opposition to the Tariff of 1828 caused its opponents to label it the Tariff of Abominations. Because of a post-War of 1812 economic downturn, several states, including South Carolina, were suffering. The new nation had suffered its first financial crisis, called the Panic of 1819; and South Carolina had not really recovered. Calhoun, an early proponent of the American System, had supported, then opposed a couple of earlier tariffs, passed in 1816 and 1824. (The first one placed a 25-percent tax on a host of goods; the 1824 tariff raised that figure to 35 percent. Among the goods heavily taxed were cotton, hemp, iron, and wool.) Neither tariff passed Congress with anything approaching The Second Bank of the United States helped fund these programs for a time but eventually fell victim to fierce opposition from Jackson, in particular, and many in Congress as well. Jackson's veto of the bill to renew the Bank's charter effectively neutered the bank. Congress did not have the votes to override, and the Bank expired when its charter ran out, in 1836.

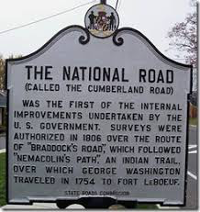

The focus on transportation infrastructure had perhaps the most success. Congress passed the General Survey of Act of 1824, providing for the Corps of Engineers to conduct periodic surveys of transportation routes of national importance. Congress also voted funding for transportation programs, including money for canals and roads. Canals and roads criss-crossed the country, enabling faster and more efficient transport of goods nationwide. Travel time to and from the West dropped dramatically, and trade and mail delivery between all sections of the country improved.One of the most well-known beneficiaries of the American System was the National Road, also known as the Cumberland Road and as the "Main Street of America." One of the most well-known canals built during this time was the Erie Canal, which linked the Great Lakes ports to the Atlantic Ocean via the Hudson River and the port of New York City. Not every proposal found support or funding. President Andrew Jackson in 1830 vetoed the Maysville Road proposal, which requested funding to construct a turnpike in Kentucky. Jackson, for the most part, was distrustful of federal power and was an opponent of much of the American System. Supporters of the American System could claim several successes for their programs. In the end, however, the Southern states never did support the plans and programs put forward by Clay, Webster, and others. The Nullification Crisis illustrated the uneasy tension between federal and state governments that was still prominent in Southern states. As well, these states had their own growing mercantile markets with plenty of domestic and overseas customers; these markets featured plenty of cotton and other agricultural products for which the supply, provided through the advent of cheap labor provided by enslaved workers, seemed endless. Clay and Webster died before the outbreak of the Civil War, and the ideas of the American System were put on hold for a time. As the nation attempted to heal itself after the war through various measures of Reconstruction, the pace of innovation in industry grew. As the 19th Century progressed, the United States took part more and more in the Industrial Revolution, building factories and railroads to keep pace with the expansion of the country's borders. The American System's ideas came back into focus during this time. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

an overwhelming majority. Both tariffs, and the 1828 one, did find a majority to approve it, along with a presidential signature, and so they became the law of the land. Virginia in 1826 passed a resolution in the state legislature, asserting that the tariffs were unconstitutional and using the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions as justification. Even though the 1828 tariff was an "abomination" in equal parts Northeast and South, depending on which state the poll would have been taking, it was the Southern states that were generally more seriously affected and one Southern state, South Carolina, that did something legislative about it. Disputes over such matters spilled over into the

an overwhelming majority. Both tariffs, and the 1828 one, did find a majority to approve it, along with a presidential signature, and so they became the law of the land. Virginia in 1826 passed a resolution in the state legislature, asserting that the tariffs were unconstitutional and using the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions as justification. Even though the 1828 tariff was an "abomination" in equal parts Northeast and South, depending on which state the poll would have been taking, it was the Southern states that were generally more seriously affected and one Southern state, South Carolina, that did something legislative about it. Disputes over such matters spilled over into the