The Cumberland (National) Road

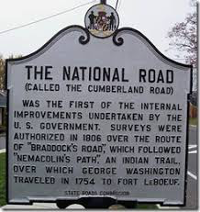

As the United States expanded in the early 19th Century by moving west, settlers found the need to build roads to help facilitate travel of more and more people. One of the first well-known federal roads was the Cumberland Road, also known as the National Road. In fact, it was the country's first federal highway, early in the century termed the "Main Street of America."

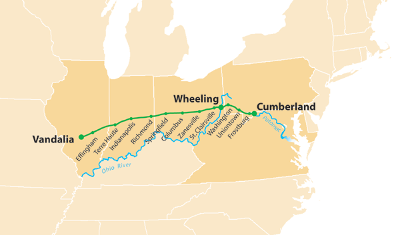

As its name suggests, the Cumberland Road had its eastern beginnings in Cumberland, Maryland. When the highway, begun in 1811, was completed in 1837, it stretched 600 miles to Vandalia, Illinois, in the new settlement hotspot the Northwest Territory (which contained what is now Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota). In 1802–1803, Ohio was in the final stages of becoming a state, yet no easy way existed for settlers to get there. Those who had explored the area and paved the way for settlement had improved on existing military trails (such as the Braddock Road, named for French and Indian War General Edward Braddock) and Native American pathways; if Ohio wanted to attract large numbers of settlers, however, the state would need a proper road leading to it. Congress passed and President Thomas Jefferson signed into law on March 29, 1806, a bill allocating resources to survey area for and then produce the Road. Then-Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin was a strong supporter of the project, and he is sometimes known as the "Father of the National Road." The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers surveyed the route and then facilitated the building of the National Road. It wasn't until 1811 that construction began. Because many of the intended users of the Road were settlers who would no doubt be bringing lots of things with them, the builders of the Road had to account for the possibility of heavily laden wagons. Dirt roads would be insufficient, for the most part, especially when turned to mud by rains. The builders employed a method of construction pioneered by John Loudon MacAdam, a Scottish engineer. The width of the road was 80 feet, wide enough to enable two wagons to pass each other without leaving the road. The roads, made of heavy gravel that at times were 18 inches deep, came to be called "macadam." The route had crossed the Appalachian Mountains and reached Wheeling, Va., by 1818. Stone mile markers placed each mile helped travelers monitor their progress. Typical travelers could go up to 15 miles a day. As well, some travelers stopped along the way, for good, setting up inns and taverns and goods stores, to help other travelers making their way west. The National Road proved more popular than Congress had envisioned, and Army Engineers had to repair parts of the Road before the entire route had been completed. The federal and state governments also connected other roads, such as the National Pike, to the National Road, creating a road network.

The Road had reached Columbus by 1833 and Vandalia, Ill., in 1837. A depression in that year, which prompted the Panic of 1837, resulted in the cessation of further federal funding. States took over the responsibility; each state was responsible for the part of the highway within that state's borders, and the states imposed tolls in order to pay for this. States built toll houses every 20 miles or so in order to collect these tolls. Another part of the Federal Government's handing over responsibility to the states was a change in focus to canals (like the Erie Canal), part of Henry Clay's American System. States began to spend money on other, non-road methods of travel as well. Construction of railroads gave settlers and other travelers yet another method of travel and transportation. The National Road continued to be a prime conduit for travel well into the 19th Century. Some of the Road and many of the bridges along the route are still in use today. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White