The Bank of the United States

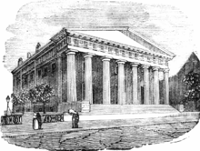

The Bank of the United States was the official bank of the U.S. Government for a number of years in the early history of the country. The Bank had two iterations, the first one beginning in 1791 and the second one ending in 1836.

The Government established the Bank in 1791, giving it a 20-year charter. The headquarters was in Philadelphia. Branches soon opened in Baltimore, Boston, Charleston, New Orleans, New York, Norfolk, Savannah, and Washington, D.C. A board of 25 directors oversaw the Bank's operations, which were essentially to act as the nation's central bank, including collecting tax revenues and making payments to foreign lenders. One main duty of the bank would be to regulate the practices of other banks, particularly those of the states. The Bank was the brainchild of Alexander Hamilton, the United States's first Secretary of the Treasury. Hamilton envisioned the Bank as a cornerstone of his overall fiscal policy for the nation, providing a stable national currency (something that the states, individually and collectively under the Articles of Confederation, had lacked). In particular, after the war, speculators bought up large amounts of land intended to be sold to settlers moving west. The speculators paid for that land by borrowing heavily from banks created just for that purpose. The so-called "wildcat" banks engaged in Hamilton also envisioned the Bank of the United States as a universal mechanism for paying off the debts incurred by the individual states during the Revolutionary War. Some states had racked up very high debts during the war; other states, by contrast, had next to none. By sharing the debt among all states, the thinking went, the national government could more quickly pay it off. To finance the bank, Hamilton envisioned the federal government putting up 20 percent of the money, in the form of government bonds; the rest would be supplied by private investors. This idea proved attractive to some people because it meant that the federal government wouldn't be funding the entirety of the bank's initial needs; however, other people found the idea problematic because of the preponderance of private money going in to public coffers. Thomas Jefferson and other Democratic-Republicans and agrarians led the opposition to the Bank, asserting that it would favor industrial interests in the northern part of the country over farm-based industry in the southern part of the country. The other main charge was that the Bank was unconstitutional because the Constitution didn't explicitly give Congress the power to establish such a federal financial institution. To this, Hamilton answered that the Constitution did, in fact, allow the federal government to set up a central bank. He cited Article I, Section VIII, paragraph 18, specifically that Congress had the power to pass any laws "necessary and proper for carrying into execution ... powers vested by the Constitution in the government of the United States." How could a federal government not have a federal bank, Hamilton argued? Financing was necessary to running a government, and paying an army, and funding government programs, and many other things. Opponents of the federal bank saw in that structure too much power in the hands of a central entity–an idea that most Americans had distrusted when that central entity was King George III and his Parliament. President George Washington agreed with Hamilton, Congress passed a bill allowing for the charter of the Bank of the United States, and Washington signed the bill into law. Twenty years later, when the charter was up for renewal, James Madison was President and his Democratic-Republican Party was distrustful of the central bank. Congress did not pass a bill for renewing the Bank's charter, and so the Bank charter expired in 1811. (The bill nearly passed. The House approved it, but the Senate vote was a tie, broken in the negative by Vice-President George Clinton, a Bank opponent.)

Without a central bank, the country ran into trouble procuring funding to finance the military effort during the War of 1812. Also during this time, state banks issued their own bank notes in growing numbers, increasing inflation and mistrust. Even though the Democratic-Republican Party was running the government, they decided to reinstate the Bank of the United States. An act of Congress established the Second Bank of the United States in 1816, again in Philadelphia. This Second Bank, which had 26 branches in 20 states and the District of Columbia, functioned more or less the same way that the First Bank did. The problem was that the country had grown even larger, with more speculators and settlers applying for more loans all of the time, and officers of the Bank issued too much credit. A decline in land values in 1819 exposed the large reliance on loans and credit. This was part of an overall harsh economic downturn that is now known as the Panic of 1819. Businesses failed, and many people struggled to make ends meet. The Bank still had its opponents, many of them vocal, and some filed a lawsuit questioning the Bank's legitimacy and power. The Supreme Court, in McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819, declared that the Constitution had granted Congress an implied power to create a central bank and that, further, the federal bank could not be constrained by a state government. (As one of the parties in the lawsuit suggests, that case involved a state bank could not legally tax the federal government.) One key difference between the First Bank of the United States and the Second Bank of the United States was that the former was owned by the federal government and the latter was a privately chartered institution. Technically, the federal government had no control over what the Bank did, anymore than it could control any other private company. The Second Bank of the United States operated in much the same way that the First Bank did, but that didn't stop opponents from pointing out the difference and the potential for unregulated malpractice. The other problem, according to Bank opponents, was that any profits made by the Bank went into the private coffers of the business, not into the federal treasury, as was the case with the First Bank. In effect, the federal government paid money in to the Bank but didn't get any money back out. One further difficulty with the Bank, according to its opponents, was that many of the investors who had put up the money to fund the bank lived in other countries and that made their motives suspect. Indeed, the U.S. Government had invested only 20 percent of the initial funds. By this time, the boundaries of the United States had moved further west, as more and more states were joining the Union. Western interests aligned with southern interests, and the Bank found more opponents. One Westerner who supported the Bank was Henry Clay of Kentucky, a member of the Whig Party. A cornerstone of the American System, a set of proposals for the federal government favored by Clay and his fellow Whigs, was a strong central bank. Clay was running for President in 1832 against the incumbent, Democrat Andrew Jackson, who distrusted the Bank. The charter of the Second Bank of the United States was due for renewal in 1836, as before. Clay, however, wanted the Bank to be a campaign issue, so he persuaded the Bank president, Nicholas Biddle, to make an early appeal for renewal of the charter. Congress approved the charter renewal in July 1832, but Jackson vetoed the bill. Congress did not have enough votes to override the veto, so the veto stood. All of this took place during the presidential campaign, and when Jackson won re-election, he took it as a sign that his position on the Bank was the correct one. He directed his Treasury Secretary, Roger Taney, to remove federal deposits from the Bank. Any federal funding earmarked for the Second Bank of the United States went instead to select state banks, which came to be known as "pet banks." Effectively neutered, the bank limped along until its charter expired in 1836. The following year, the country suffered through another economic downturn, known as the Panic of 1837. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

sometimes dubious loan practices, and confidence in the security of the overall money supply dropped as a result. If the national government had a national bank issuing a national currency, Hamilton reasoned, then that bank would have better control over such speculative loan practices because it could, with the authority of the federal government, regulate such activities.

sometimes dubious loan practices, and confidence in the security of the overall money supply dropped as a result. If the national government had a national bank issuing a national currency, Hamilton reasoned, then that bank would have better control over such speculative loan practices because it could, with the authority of the federal government, regulate such activities.