The Indian Removal Act provided the mechanism for the forced relocation of more than 46,000 Native Americans to Indian Territory. Congress passed the act on May 26, 1830, and President Andrew Jackson signed it into law two days later. It was not the first such law, just the latest and most wide-reaching. In 1802, then-President Thomas Jefferson had an agreement with the state of Georgia, the Compact of 1802, that, in essence, ousted Native Americans from the land on which they had been living in what became the states of Alabama and Mississippi. Jefferson led the way to another forced removal the following year, in the form of the Louisiana Purchase, which transferred a very large amount of land from French hands to American. The eventual settlement of that territory by Americans led to many conflicts with Native Americans.

The Indian Removal Act began its life in the Senate in February 1830. A very close vote followed a contentious debate, punctuated by a six-hour speech against the measure, given by Theodore Frelinghuysen, a New Jersey Senator who was later twice a vice-presidential candidate. Also among the high-profile Senators who opposed the act were Henry Clay, Davy Crockett, and Daniel Webster. The Senate ultimately passed the bill after a vote of 28–19, on April 26. Exactly one month later, the House passed the bill, after a vote of 103–97. (One of those to speak out against the bill in the House was future President Abraham Lincoln). Two days later, Jackson signed the bill into law.

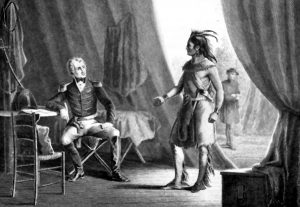

Jackson had a long history with the issue of battling with Native Americans over their homelands. As a military commander, he had faced off against Creek and Seminole forces; he had also benefited from a large contingent of Native American allies, Cherokee in particular, at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. On the other hand, he had played a part in negotiating a large handful of treaties with other tribes, the result of which was exactly what the federal Indian Removal Act did–provide for the relocation of thousands of people, some voluntary but a great many not. Among the states in which white settlers benefited from the removal of so many Native Americans were Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

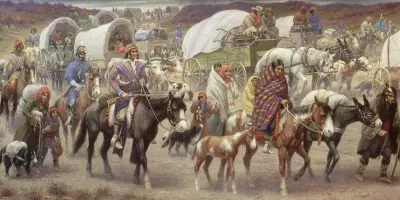

The first agreement between American and Native American authorities after the passage of the Indian Removal Act was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Under the terms of this agreement, the Choctaw in Mississippi gave up the right to live on land east of the Mississippi River. This was according to the wording of the law, which also nowhere included the word "mandatory" when describing the exodus. The idea was a land exchange: the lands that Native Americans were now living on, in exchange for lands otherwise designated for them, Indian Territory. Although many European settlers undoubtedly thought that what they were offering was one thing in exchange for another equal thing, in reality it was not at all the same: Native Americans were being asked (and, in many cases, told) to uproot themselves and their families–leaving behind generations of farming and neighborhoods and family history–and put down new roots hundreds and hundreds of miles away. Understandably, many Native Americans resisted, sometimes violently so. The five tribes most affected by the Indian Removal Act were the so-called Five Civilized Tribes–Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole. They were called that because they had already adapted somewhat to living within "civilized" borders.  The Cherokee, in particular, had several trappings of "civilization": They had their own written language, thanks in large part to Sequoyah, and they had their own newspaper. They had their own schools. And, providing framework for all of that was their own constitution and their own supreme court. They considered themselves very much a sovereign nation. Despite all of this, they found themselves on the wrong end of American intent and desire for land to settle. No matter how many Cherokee protested against the removal, more and more armed soldiers appeared, forcibly enforcing the emigration "agreement." The impact on Cherokee was especially harsh, as thousands and thousands were uprooted from their ancestral homes and forced to travel thousands of miles to a new "home." Nearly one-quarter of the Cherokee died on the journey, which was termed the Trail of Tears. One Native American people who forcefully resisted such removal were the Seminole. The result was the Second Seminole War, which lasted seven years, extending through the end of Jackson's second term (He had been re-elected in 1832.), the entirety of the presidency of Martin Van Buren, and half of the term of John Tyler. Seminole resisters finally surrendered, and most of them moved. (A few escaped into the surrounding swamps.) All of this happened after Seminole representatives signed the 1832 Treaty of Payne's Landing. In the same year, Creek representatives signed the Treaty of Cusseta and Chickasaw representatives signed the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek. Other tribes affected included the Kickapoo, Lenape, Potowatomi, Shawnee, and Wyandot. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White