The U.S. Government undertook a series of initiatives in the 19th Century to remove Native Americans from their ancestral homes, in order to make way for European settlers. The most devastating of these, the forced migration of tens of thousands, has been called the Trail of Tears.

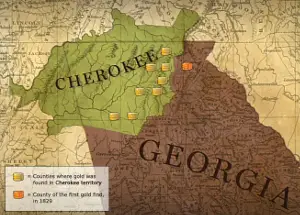

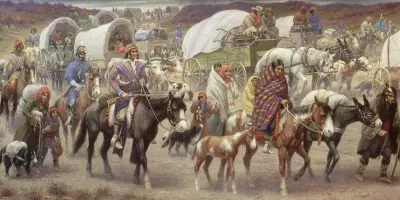

Especially contentious was the fight between Georgia European residents and Native Americans, particularly Cherokee, living within that state's borders. Tensions had grown since the founding of the Georgia colony in 1733 and then the State of Georgia in 1788 and had only worsened after the discovery of gold near Dahlonega in 1829, as gold-seekers trespassed on Cherokee land in search of a quick fortune. The Georgia legislature, in the late 1820s and early 1830s, passed laws that abolished the Cherokee government and laws that voided their right to any sort of land ownership, setting up a lottery system for dividing up lands to be seized among the European settlers. In response, Cherokee filed suit in federal court, citing what they believed was a solid case: That because the U.S. Government had signed treaties with them, such as the 1785 Treaty of Hopewell, as equals, then that meant that they were a nation unto themselves. The final arbiter of American law, the Supreme Court, handed down its decision in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia. Chief Justice John Marshall, writing for the Court, said that the Cherokee were not a sovereign nation but that they, and other Native American tribes, were "domestic dependent nations" and that the relationship between them and the U.S. Government was akin to that of a ward and a guardian. Marshall drew a clear distinction with regard to state law, however: The relationship was with the federal government, not with state governments. As such, Cherokee living in Georgia were not subject to Georgia state laws that required their ouster. A follow-up case made it to the Supreme Court, and Marshall, again writing for the Court, delivered a similar decision, writing in Worcester v. Georgia that all of Georgia's state laws having anything to do with Cherokee living within Georgia state borders were null and void. This should have been the end of things as far as the State of Georgia's being able to force Cherokee living within Georgia's borders to leave their lands. However, Georgia state officials chose to ignore the Supreme Court decision, as did President Jackson. A quote often attributed to him that historians don't think he said in so many words was "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" Jackson did write something similar in a letter to John Coffee, one of his negotiators with Native American tribes. Cherokee officials, among them the Principal Chief, John Ross, met with Jackson several times in order to find some common ground, but Jackson would not budge. His position was that Native Americans should make way for Europeans. He had held that position since his earliest interactions with Native Americans in his days as a young soldier in the Old Northwest, and he wasn't about to change his mind. What this meant in practice was that federal officials, notably members of the military, would not prevent Georgia officials from enforcing the laws that they had passed with an eye toward disenfranchising Cherokee and removing them from state borders. In effect, this was a form of nullification, in that Georgia was allowed to ignore a Supreme Court decision that should have invalidated a series of state laws. (It was not the same form of nullification as the one attempted by South Carolina, which created the 1833 Nullification Crisis.) Also at this time, a number of Cherokee wanted to find a peaceful solution and were open to picking up and moving if the U.S. Government was willing to abide by what they seemed to have promised with the words that formed the Indian Removal Act, an 1830 federal law that provided the legal basis for forced emigration and the mechanisms to enforce that emigration. It was at the insistence of these "Treaty People" that a large number of Cherokee (including the influential Elias Boudinot, publisher of the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper, and John Ridge) eventually supported the 1835 Treaty of New Echota, out of which Cherokee gave up all rights to lands east of the Mississippi River and got in return a sum of $5 million, payment in yearly installments; $500,000 for education; full compensation for all property left behind; and, echoing the language of the Indian Removal Act, the promise that the lands in their new "homes," for which they had left behind their ancestral homes, would be theirs to own in the future, without restriction. The idea of approving the emigration divided the Cherokee nation. John Ross opposed the treaty and submitted a petition to the U.S. Government protesting the treaty; more than 15,000 other Cherokee signed the petition. The Senate approved the treaty, by one vote.  The Treaty of New Echota resulted in a large-scale forced emigration of Cherokee in 1838 and 1839 because the treaty also allowed the U.S. Government to call in armed soldiers to enforce the migration. By 1838, only about 2,000 Cherokee had left Georgia. As a result, about 7,000 members of the U.S. Army, some militia groups, and a few volunteer groups, commanded by future Mexican-American War hero Winfield Scott, rounded up twice their number of Cherokee and installed them in holding camps near Cleveland, Tenn., until they were allowed to begin their journey westward.  More than 5,000 of these people died on the way, forced as they were to travel with the barest of necessities through harsh terrain in unforgiving winter weather. Clothing was scarce, as was food and shelter. Most walked, many without anything on their feet. Some went by water, traversing various rivers along the way; for these migrants, being in boats was the only upgrade. Causes of death included cholera, dysentery, typhus, and whooping cough, not to mention starvation. The Cherokee words for this mass exodus are Nunna daul Isunyi; the English translation is "The trail where they cried." From this comes the term the Trail of Tears. It was used to describe the wider diaspora than just the Cherokee exodus. Choctaw and Creek in similar numbers both emigrated and died along their own Trail of Tears. Many high-profile Native American leaders who agreed to treaties or were not seen to be resisting enough were killed; among these were the Cherokee Boudinot and Ridge and the Creek William McIntosh.

Members of the Chickasaw tribes fared slightly better, making the same journey but surviving in greater numbers. Once in Indian Territory, Chickasaw joined with Choctaw in great numbers. Many Cherokee and members of other tribes made it to their destination, reaching at first the settlement of Tahlequah, where many stayed. Others moved further within what was then called Indian Territory. The U.S. Government later reneged on its promise of land ownership in perpetuity, first with the Oklahoma Land Rush, in 1889, and then, nine years later, dissolved the political systems under which the tribes had been governing themselves as dependent nations. In 1907, Indian Territory and Oklahoma Territory dissolved into the State of Oklahoma.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White