The Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age was a period of about a century in which the Netherlands ruled supreme in commerce, culture, and learning. Historians differ on the exact beginning and end point of the Dutch Golden Age Many tie the beginning to the formation of the Dutch Republic, in the late 16th Century, and the end to the Third Anglo-Dutch War, which ended in 1674. Others date the beginning to the early 17th Century and the end to the resolution of the War of the Spanish Succession, in the early 18th Century. What historians generally agree on is that during all of these years, the Dutch were leading the way in several significant areas.

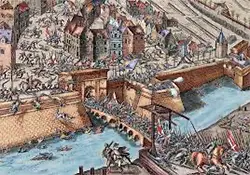

The Dutch Republic began in the shadow of the Eighty Years War, a struggle against the forces of the Holy Roman Empire and, specifically, Spain's King Philip II, who had inherited rule of the Low Countries from his father, Charles V, when the latter abdicated in 1556. The seven provinces in the north of the Low Countries at that time were a hotbed of Protestantism activism, with the various authorities encouraging toleration of religious practice in a way that the Catholic Holy Roman Empire did not. Those seven provinces, in the face of armed incursions aimed at bringing them into line religiously, banded together and formed the Dutch Republic, as embodied in the Union of Utrecht, in 1579. The largest city in the Low Countries at that time was Antwerp. Spanish troops there had gone on a rampage in 1576, burning a significant part of the city; in response, the people in the city threw in their lot even more with the seven provinces and Antwerp, after joining the Union of Utrecht, became the capital of the Dutch Revolt. Spanish forces were fighting in various places during this time; in 1584, they pooled their efforts and made Antwerp the target. Spanish troops besieged Antwerp, cutting off access via the vital River Scheldt; to counter this, Dutch forces flooded the surrounding lands, in an attempt to prevent the effectiveness of Spanish troops to move from nearby forts into the Antwerp area. Further Dutch efforts included an attempt to break the Spanish blockade, spearheaded by a giant ship named, in English, the End of War. The Spanish forces held, and the siege continued. Out of options and low on food and medicine, the people in Antwerp surrendered, on August 17, 1585. Rather than sack the city, the Spanish stationed troops there but otherwise left it to recover. By this time, more than half of the population had migrated north. This included many captains of industry and major players in the financial sector; their ending up in Amsterdam swelled that city's pride and potential, and it became the economic center of the Dutch Republic. (The migrations also swelled that city's population, which doubled between 1570 and 1600.)

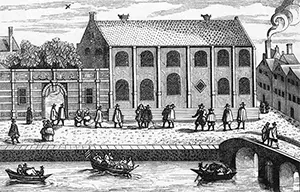

In the first decade of the new century came the Amsterdam Exchange (following the model of the Rotterdam bourse) and the Exchange Bank. Dutch trade, powered primarily by a very large merchant navy, brought large amounts of money into the republic's coffers, the result of trading in new and exotic materials like coffee, silk, sugar, and (above all) spices. Dutch banking became a model for other European countries to follow. Internally, industries such as shipbuilding prospered considerably, filling a growing demand for means of exploration and goods shipment from the Republic's increasingly far-flung trade network. Coordinating all of that trade were two economic entities, the East India Company and the West India Company. The former, known as the VOC, came first, in 1602, and was by far the more dominant of the two, presiding over an exponential increase in trade in the Eastern Hemisphere. In 1621 came the West India Company, known as the GWC and having a focus on Western Hemisphere interests. Bringing spices and vegetables back from overseas and selling them for high prices became the norm, and Dutch coffers overflowed with foreign capital. As well, the geographical location of the Republic–in the center of Europe and so at the nexus of much east-west travel and trade–served to benefit Dutch success. For several years, the Dutch navy was the largest in the world. For several years, the Dutch trade network and consequent income were the largest in the world. Infrastructure improvements included the building of canals, to link the various cities and towns, improving the efficiency of travel of both goods and people. Powering an increase in agricultural production were a number of new mills, generating power through wind (thus the enduring symbol of the Dutch windmill), and the use of peat as a fuel. In the same vein, Dutch engineers embarked on endeavors of land reclamation through the use of polders, made possible through the draining of some waterways and flood-prone areas and used on the guidance of famed hydraulic engineer Jan Leeghwater. All of this made the Republic thrive. Also powering the Dutch economy was the practice of slavery. Much of the labor employed by Dutch interests overseas was enslaved. The GWC had jumped into the slave trade during the war with Portugal, and this was the most lucrative commodity remaining when the GWC ended, in 1674. Slavery, however, did not end in Dutch colonies, for many decades.

The Dutch tolerance for religious practice extended to the pursuit of knowledge in other areas. Officials encouraged active study and education. William the Silent had founded the University of Leiden in 1575, and this institution became a haven for learning. The university encouraged active study, particularly in the sciences. The Dutch Republic became quite a haven for thinkers from other countries as well. The famous French philosopher Rene Descartes lived in the Republic for more than two decades. Well-known English philosophers Thomas Hobbes and John Locke both spent considerable time in Dutch lands. Another famous Frenchman to reside in the Republic was Pierre Bayle, who fled religious persecution in his home country and served as a professor in Rotterdam, later publishing his famous Historical and Critical Dictionary. He, along with Hobbes, benefited from the Republic's tolerance policies, succeeding in publishing books that they could not have in their homelands. Other authors enjoyed similar success, and the Dutch publishing business thrived. Perhaps the two most famous Dutch scientists of the period were Christiaan Huygens and Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who excelled in the fields of astrophysics and biology, respectively. Leeuwenhoek was the first known scientist to describe bacteria, an outgrowth of his pioneering work in microbiology. Among the accomplishments of Huygens were the invention of the pendulum clock and a description of the workings of the rings of the planet Saturn. Also living in the Dutch Republic during the Golden Age was Hans Lippershey, the inventor of the telescope, which he called "Dutch perspective glass"; he demonstrated his invention for the first time in 1608.

Also flourishing during the Dutch Golden Age were a large handful of artists, primarily painters, some of whom became world-famous. The most well-known was Rembrandt van Rijn, whose The Night Watch (left) was emblematic of the large group portrait style favored by Dutch painters of the period. His countryman Johannes Vermeer excelled at many elements of painting but particularly at portraits, as exemplified in Girl with a Pearl Earring (right). Other genres of painting emblematic of the period were still life settings and landscape settings, epitomized by the works of Jan Brueghel and Jacob van Ruisdael, respectively. Dutch painters added their own element of abundance to the still life, creating a style known by its Dutch name, pronkstilleven (Ostentatious Still Life). Dozens of Dutch painters excelled in other genres, particularly historical settings. The influence of all of these artists extended well beyond the borders of the Republic and on into subsequent generations. The Dutch Republic far outlived the Dutch Golden Age. Tulip Mania might have been an isolated incident, but Dutch fortunes did decline as the 17th Century advanced. Other European nations gained at the expense of the East India Companies, taking away not only trade but also territories. The sprawling nature of trade was increasingly too much of a drain on the central economy. Although Dutch sailors could rightly claim victory over England in the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the fighting had so exhausted both countries' resources that the Dutch Republic scored very few real gains as a result. By the time that yet another William of Orange became England's King William III, the Dutch Republic was mired in struggle. Dutch troops fought alongside British troops in the War of the Spanish Succession, during the first quarter of the 18th Century. The war ended the way that the Dutch wanted it to, but the war had also drained the republic's coffers and much of the financial reserves. Things were so bad that the Republic struggled for a time to pay interest on its national debt. The Golden Age was but a memory. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White