The Dutch Tulip Bubble

The Dutch Tulip Bubble was an economic episode that bankrupted many individuals and cost many others their credibility but left the government and its treasury and reputation largely unscathed. Many people also refer to this episode as Tulip Mania.

Tulips came to Europe from the East Indies in the 16th Century. The Netherlands by this time had begun trade routes in that area of the world, and Dutch ships were bringing home vegetables and exotic spices to sell in their own markets, to domestic and international customers. In the 1600s, Dutch growers began to produce their own tulips, finding that the Low Countries conditions were amenable to tulip production. They discovered that flowers grown from seed took a long time, whereas flowers grown from bulbs took a much shorter time. People in the Dutch Republic considered tulips themselves to be exotic and paid high prices for them, especially with the idea of having a bulb that was its very own money-making device. The discovery of tulips that had multiple colors (the product of a virus) sent the price of such items skyrocketing. Some estimates had it that people were willing to pay six times the annual salary of a middle class worker for just one tulip. People of all economic classes waded into the fray, desperate to obtain something that they considered to give them status, even if it meant paying beyond their immediate means.

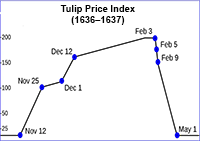

Because the tulips bloomed for only about a week, the people who sold them had a limited window of sale–that is, until growers began to sell their tulips before they were in bloom. Buyers agreed to pay a certain price for tulips and signed a contract to that effect; then, when the flowers bloomed, the growers would hand over their tulips and the buyers would hand over their money. Such practices are much more commonplace in modern times; in those days, such things were rare. As well, traders sold their purchases on to others, many times on the very same day. The known extreme is that some bulbs changed hands 10 times in one day. Demand for tulips came from all over Europe. In 1634, the call for tulips from France was overwhelming and prices spiked astronomically. Contract buying continued, and sales did not wane. Such was the case for two years running. Even "ordinary" tulips sold for large amounts of money at this time.

It all came crashing down in 1637, however. It began in February in Haarlem, when many buyers refused to show up, citing concerns over an outbreak of bubonic plague and, in some cases, a general distrust of the process. Other tulip growers experienced similar frustrations and were left with flowers they could not sell. Exacerbating the problem was the fact that many buyers had agreed to buy tulips on credit, anticipating repaying their loans when they turned around and sold their bulbs to someone else. Demand plummeted; so did prices. Some people swallowed their pride and sold what they could at rock-bottom rates. Others took to the courts, to try to enforce the terms of a contract that was, technically, legally binding. A great many growers stopped altogether, not wanting to repeat the frustrations of what later economists would call the Tulip Bubble.

The Dutch people (particularly Dutch Golden Age painters) held their fascination with tulips beyond the end of Tulip Mania. To this day, tulips are a big deal in the Netherlands. The price paid for such items is correspondingly much lower, however. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White