The Dutch East India Company (VOC)

The Dutch Republic formed the Dutch East India Company in 1602, primarily as a means to protect Dutch trading interests in Asian waters but also as a way to help the Dutch fight for independence from Spain. The name of the company in Dutch was Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie and is sometimes abbreviated as VOC; indeed, the company's logo was those initials and was recognized around the world for many years.

The company enjoyed a trade monopoly in a wide-ranging area of influence, from the Cape of Good Hope to the Straits of Magellan. Company officials had the power to make treaties, build forts, and otherwise protect their investments.

The Dutch had joined the pursuit of international trade mainly to obtain their own supplies of spices found in the Far East. A series of expeditions to Indonesia took place on either side of the turn of the 16th Century, with captains such as James Lancaster, Cornelis de Houtman, Jacob van Neck, and Frederick de Houtman leading the way. The VOC's main opposition in this area was Portugal, who had a centurieslong head start and, naturally, controlled most of the trade routes in the area. One exception to this was the Moluccas, also known as the Spice Islands, which Dutch ships under van Neck reached in 1598. Controlling that trade were native Java profiteers; violence between Dutch and Javanese ships ensued, and the Dutch prevailed. Dutch success also came at the hands of the Portuguese elsewhere in Indonesia, notably on Ambon Island, another of the Moluccas. The formation of the VOC was to protect this trade. Among the spices sent back to be sold in European markets were cinnamon, cloves, mace, nutmeg, and (especially) pepper. Like other companies and organizations of the time, the VOC relied on slave labor to power the enterprise and engaged in the slave trade, both for their own efforts and as a means of financing their profit-making. It wasn't long until VOC trading posts dotted the landscape: in India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Mauritius, South Africa, Thailand, and Vietnam. In the latter half of the 17th Century, the VOC became the richest private company in the world, boasting nearly 200 ships, 10,000 soldiers, and tens of thousands of employees staffing offices on multiple continents and around the world. Investment in the company proved very lucrative for its backers. The VOC headquarters was first in Ambon but later moved to Batavia. Running the VOC starting in 1610 with Pieter Both were a series of governors-general. Their terms of service varied, from one year to (in the case of Joan Maetsuycker) 25 years. Their administration produced a thriving enterprise in the islands of Indonesia, displacing or at least outdistancing English and Portuguese interests.

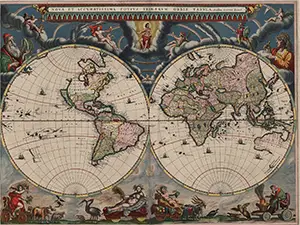

The VOC also sponsored voyages of discovery, including Henry Hudson's voyage in search of a northeast passage and the expeditions to the Southern Hemisphere of Willem Janszoon, Pieter Nuyts, Abel Tasman, and François Thijssen including sightings of what became Australia and New Zealand. Indeed, Dutch explorers gave names to these lands: New Holland (what is now Australia), New Zealand (still its name), and Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania). Mapping all of their achievements were the well-known cartographers Joan and William Blaeu. Not surprisingly, other European countries found Dutch expansion troublesome. England, in particular, was willing to respond militarily. The two countries fought three wars from 1652 to 1674. By and large, the Dutch emerged the stronger after these conflicts. England's Glorious Revolution, in 1688, which put a Dutchman on the English throne, cemented an alliance between the two states.

The VOC diversified in the 18th Century, pivoting to trade in coffee, cotton, sugar, tea, and textiles–all of which were in high demand in Europe. Dutch traders had stockpiled precious metals that they had received in exchange for spices in the previous few decades, enabling them to engage in new trade. Those new markets proved very lucrative but also involved new challenges, particularly since the VOC did not have a monopoly on those new goods, no matter how popular they were back home in Europe. In addition, goods such as sugar came from various places around the world and so buyers didn't have to obtain supply of such goods from the VOC. Dutch and English forces again went to war in 1780, nearly a century after the last conflict, just as the latter's war against its American colonies was winding down. Much had changed in the century since the last war. The Netherlands, in particular, was on the decline, even as the British star was on the rise. Dutch money and weapons helped to finance the American war effort, and it was the Dutch governor of St. Eustatius, Johannes de Graeff, who first saluted the flag of the United States, in 1776. The fledging United States established diplomatic relations with the Dutch Republic in 1782; this did not translate into a formal alliance, however. In the intervening years, Dutch ships and leaders engaged in actions that Britain thought increasingly hostile, and a declaration of war came in 1780. British ships commenced a blockade of the Dutch homeland that rendered that part of the conflict relatively tranquil. The one exception was the 1781 Battle of Dogger Bank, which was inconclusive. Britain also targeted Dutch ports and other colonial properties around the world. British troops took particular delight in capturing and then sacking the Dutch holdings on St. Eustatius, in 1781. The victors had similar successes elsewhere in the West Indies, although the Dutch held on to Suriname. The VOC had declined along with the Dutch navy during the latter half of the 18th Century, and the former had to request help from the latter in order to defend its positions in Asian waters. As elsewhere, British forces were victorious for the most part. Britain gained at Holland's expense, militarily and economically. The Batavian Revolution replaced the Dutch Republic with a new government, which took over the VOC in 1795. By then, the once proud, very lucrative company was a shadow of its former wealth. The government allowed the company charter to expire at the end of the century, and the VOC was no more. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White