The Eighty Years War

Part 1: European Intrigues The Eighty Years War was a struggle between Spain and the Low Countries for supremacy in the 16th and 17th Centuries.

In the 15th Century, a number of Dukes of Burgundy had expanded their borders northward, absorbing more and more of what is now the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands). France's King Louis XI took over the Duchy of Burgundy in 1477, leaving what came to be known as the Burgundian Netherlands under the sovereignty of Mary, last of the Valois-Burgundy line; five years later, Mary died and the rule of the Burgundian Netherlands nominally passed to her son, then Philip I of Castile, in Spain. In 1500, Philip and his wife, Joanna, had a son, named Charles.

When the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (left) was born in Ghent, in 1500, he was heir to the Burgundian Netherlands through his heritage in the powerful Habsburg family. When his father died, in 1506, Charles was nominally in charge of the Netherlands. He expanded his realm a decade later when he became co-ruler of Spain. Three years after that, he succeeded his grandfather as ruler of Austria. Finally, in 1530, Charles won selection as head of the Holy Roman Empire. The following year, Charles introduced three councils into the Burgundian Netherlands: the Council of Finances, the Council of State, and the Privy Council. Filling these councils were Low Countries nobles, who served as advisors to Mary of Hungary, Charles's regent in the Netherlands.

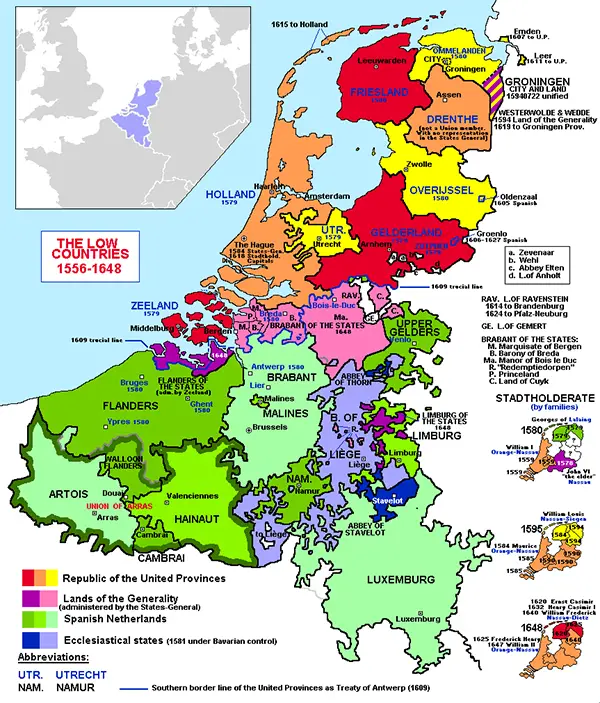

The Seventeen Provinces of the Low Countries were these:

Emperor Charles V alienated many in the Low Countries in two fundamental ways: by increasing their taxes without extending them any kind of consequent benefit and by challenging the rise of Protestantism. Each had its own set of difficulties.

The taxes imposed on the Low Countries–and those taxes were imposed on other parts of the Holy Roman Empire as well–helped to finance wars against France and intrigues in Italy and to contain an uprising in Spain. Nominally, trade flowed between the Low Countries and all of the Empire's antagonists. The war over which monarch ruled the Kingdom of Naples, say, didn't so much protect the people in Flanders or Guelders from attack; rather, it kept them from doing business in Naples. As well, people in the Low Countries chafed under the Habsburg yoke, and having to pay for a faraway war would have exacerbated those ill feelings. At the same time, the Low Countries were a haven for Protestant thought and activity. John Calvin, primarily, but also other leaders of the movement against or away from Catholicism found safe havens in the Low Countries, particularly the northern provinces. Charles tried to suppress Protestant activity and even thought in the Low Countries by reinstating the Inquisition; it didn't last long. Charles V abdicated his thrones in 1556. Taking over as King of Spain was his son and heir, Philip II. Eventually named as Holy Roman Emperor was Ferdinand I, Charles's younger brother.

Philip II carried on his father's proposals of taxation and suppression of Protestantism but with a heavier hand. Further, to protect against subsequent incursions from France, Philip ordered troops to remain in the Low Countries. Residents there who already felt themselves overtaxed now had to pay for this "protection force" as well, in both money and exasperation. Resentment grew. Charles had been born in the Low Countries and had identified with the feelings of the people there, to an extent. Philip, born in Spain, had none of those sympathies and displayed little empathy toward the people's concerns. In protest, some nobles resigned from the Council of State. Among those were three very prominent men: Lamoral, Philip de Montmorency, and William the Silent, more well-known as the first William of Orange. One way in which the residents of the Low Countries expressed their displeasure with such measures of repression as the return of the Inquisition was to practice iconoclasm, the damaging or destruction of monasteries and their contents, such as statues and other art works depicting Catholic religious figures. This violent form of expressing anti-Catholic sentiment had proponents in other Protestant areas as well. In all, the 10 southernmost provinces were generally controlled by Spanish Catholics. The seven provinces in the north were the hotbed of Protestant resistance. Philip sent the dedicated Duke of Alba, at the head of 10,000 soldiers, to enact measures of repression in the Low Countries. Among his measures was to bypass Margaret of Parma, half-sister to King Philip II and the intended governor, and act as his own ruler, ordering reprisals and executions, including of powerful nobles, of anyone who opposed Philip and Catholicism. Among those executed were Lamoral and Montmorency.

William of Orange (right) was one of those who organized the resistance. He and many others had signed petitions to Margaret and Philip, imploring them to find peaceful resolutions to the disputes; their pleas went unheard. As stadtholder of Holland, Utrecht, and Zeeland, William had a powerful position and powerful friends. He also had allies elsewhere.  Protestant armies from both France and Germany invaded the Low Countries in 1568, in support of the resistance. William's forces, after suffering a defeat at Rheindalen in April of that year, enjoyed a significant victory at the Battle of Heiligerlee, in May, but the defenders found themselves outclassed and certainly outfunded by Philip and Alba. William of Orange left the country, and the repression continued. Historians generally regard that battle, Heiligerlee, as the start of what was later called the Eighty Years War. After a four-year period out of the sights of Alba and the Spanish, William of Orange was once more in the Low Countries, in Delft, directing the resistance. William had also pursued other alliances, including with both England's Queen Elizabeth I and the Ottoman Empire's Suleiman the Magnificent, the latter already fighting Philip for supremacy in the Mediterranean. When William returned to his homeland, he won ascension to the position of Governor-General and was regarded as the overall leader of the resistance. In 1573, Philip became convinced that neither the man, Alba, nor the policy, repression, was to be continued so vigorously. Luis de Requesens became Philip's representative in the Low Countries and found himself tasked with trying to pursue a policy of moderation. His attempts before he died, after just three years, had not succeeded. Meanwhile, the Low Countries had united behind William of Orange and agreed to their own arrangement, the Pacification of Ghent. This was significant because it included the provinces that were Catholic. The newly expended resistance continued. The conflicts had been fierce and, in some cases, long-lasting. Spanish forces had taken Haarlem in 1573 after a protracted siege but had, the following year, failed to take Leiden. Other cities changed hands, sometimes again and again. Next page > Struggle for Supremacy > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White