The Eighty Years War

Part 2: Struggle for Supremacy Spain was struggling with money problems at this time (and, indeed, throughout Philip's reign). At times, Spanish mercenaries went unpaid. One explosive reaction to this came in It turned out later that English ships had intercepted a large amount of money meant to pay the soldiers; but that made little difference to Philip, the soldiers themselves, or the aggrieved residents of Antwerp. The unity continued for a time. In 1579, three of the southern provinces signed the Union of Arras and agreed to ally with Philip. In response, William of Orange brought together five other provinces in the Union of Utrecht. As well, in 1581, the States General, a representative assembly originating with the creation of the Burgundian Netherlands a century before, formally ousted Philip II with the Act of Abjuration, replacing him as sovereign ruler with François, Duke of Anjou, whose older brother was France's Henry III. Even though Henry III was a Catholic monarch pursuing his own war against Protestants, the people of the northern Low Countries preferred an indirect link to Henry III to a direct link to Philip II. As it turned out, the trust given François was misplaced. He arrived in 1582, at the head of a small army, and within a few months tried to take Antwerp for himself. After revoking the offer of sovereignty, the States General tried to recruit Elizabeth I of England, but she demurred. The frustrated States General decided to do the governing themselves. Meanwhile, the Spanish forces had found rejuvenation under the Duke of Parma and reclaimed a large part of the Low Countries, including Breda, birthplace of William of Orange. A supporter of Philip II killed the popular resistance leader in 1584. The next year, Spanish troops took control of Antwerp. In desperation, the States General appointed Maurice of Orange (son of William) to be their leader.

As the 16th Century wound down and the fighting continued, the Dutch army more and more resembled the kind of hard fighters that Parma had brought with him from the beginning of the war. In just two decades, the Dutch army tripled in size. Dutch forces even took the offensive, in the 1590s taking the siege to several Spanish-controlled centers, including the well defended Coevorden. Spain was not focused exclusively on the war in the Low Countries for much of its early years. Spanish forces gained territory and rounded out resistance fighters in fits and starts. In 1588, however, Philip II turned his anger fully on England. The grand Spanish Armada aimed to turn its full firepower on English ships and shores but ended up retreating in failure. Spain had also become embroiled in the French Wars of Religion; and in 1579, Philip endeavored to prevent Henry of Navarre from taking over the French throne. Philip found himself again thwarted, as Henry became King Henry IV and then dealt Spanish forces a series of blows, in Burgundy and at Amiens. The Peace of Vervins, in 1598, ended the fighting between France and Spain.

In that same year, Philip II died. He had named his older daughter, Isabella–together with her husband, Albert–rulers of the Netherlands. In the Low Countries, Maurice of Orange continued to rally the troops and take back territory from the Spanish. Among the victories was a naval one, at Gibraltar in 1607. As the 17th Century began, Spain and the Low Countries were still at war, but the fighting was taking place mainly around the borders. In the main centers, trade and economy flourished. Dutch ships sailed far and wide, powering the enterprise of the Dutch East India Company, created in 1602. Dutch ships also attacked overseas colonies belonging to Portugal, which Philip had absorbed into his empire earlier in his reign. Spain was forced to spread its resources ever more thinly. By 1609, both sides realized that the borders were probably set: in the north were the Protestant Netherlands, and in the south were the Spanish (Catholic) Netherlands. By that time, Philip II had died and been replaced on the Spanish throne by his son, Philip III. Representatives of the two sides met at The Hague and hammered out a ceasefire, to last a decade and two years. This was the Twelve Years Truce.

The two lands consolidated their holdings and looked outward for nearly a decade. In 1618 began the Thirty Years War, which involved all the major powers of Europe eventually. The Dutch got involved early on because Maurice of Orange's nephew was Frederick V, Elector of the Palatinate, whose assuming the throne of Bohemia and public proclamation of his Protestant faith made him an enemy of Catholic entities like the Holy Roman Empire. When the Twelve Years Truce expired, Spain and the Low Countries went back on the attack against each other. That struggle dragged on, as did the wider war. In 1625, Spanish forces captured the strategic city of Breda and Maurice of Orange died, leaving the Low Countries in need of a new leader. Frederick Henry, half-brother to Maurice, took up the mantle and had great success, forcing the thought-to-be impregnable fortress of 's-Hertogenbosch to surrender in 1629 and, in the March along the Meuse a few years later, capturing Maastricht and other major cities.  At the same time, Dutch and Spanish ships were slugging it out on the high seas, economically and militarily. Dutch ships at times raided Spanish treasure fleets and had a go at conquering some Spanish possessions in the New World. The Dutch had far more success in setting up and protecting their trade routes in the East. Spain powered up for one last large attack in 1639. A fleet of ships carried 20,000 troops to the Flanders area, intending to bring the northern resistance down. The Low Countries forces were ready and successful, triumphing at the Battle of the Downs. As it turned out, this was the last Spanish attempt to impose its will on the north. The Netherlands allied with France, and Spain looked for peace. The 1648 Treaty of Münster ended the war between the Netherlands and Spain, as part of the Peace of Westphalia. As a result, the Dutch Republic became an independent entity, and the Spanish Netherlands remained Catholic. First page > European Intrigues > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

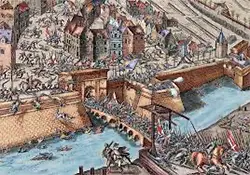

November of 1576, when a group of Spanish soldiers who were part of the Army of Flanders turned their full frustration with the war and with their inability to get support or money on the city of Antwerp. For three days (Nov. 4–6), the troops sacked the city, at once the Low Countries' center of culture and finance. Deaths exceeded 7,000. Looting and destruction ensued on a large scale.

November of 1576, when a group of Spanish soldiers who were part of the Army of Flanders turned their full frustration with the war and with their inability to get support or money on the city of Antwerp. For three days (Nov. 4–6), the troops sacked the city, at once the Low Countries' center of culture and finance. Deaths exceeded 7,000. Looting and destruction ensued on a large scale.