The French King Louis XI

Louis XI was King of France in the latter half of the 15th Century. He did much to restore prestige in the monarchy and solidify its control over the realm.

He was born on July 3, 1423, in Bourges. His father was Charles, whose father had been King Charles VI. Because of a treaty signed by that king in 1420, the king's son was not the Dauphin, or heir to the throne. Thus, when Charles VI died in 1422, his son Charles was not technically the King of France. The English king Henry V had died in that same year, and his infant son, also named Henry, was declared King of England and King of France. Because England controlled much of France at this point in the progress of the Hundred Years War, the claim of Charles to be King of France wasn't as strong as it otherwise have been. Nonetheless, Charles styled him King of France and set up a court at Bourges and a Parliament at Poitiers. It was at that royal court that Louis was born. English armies were still winning victories in France in Louis's early years, and so the boy grew up behind the walls of a fortress, at Loches. Isolated, he threw himself into his studies, mastering history, mathematics, rhetoric, and science on the academic side of things and also learning how to ride a horse and how to fight, using bow and arrow, lance, and sword. He wasn't surrounded by the trappings of royalty and so grew up having simple needs and enjoying simple pleasures. When Louis was 10, he went to Amboise to live with his mother, Marie. The older he grew and the more he saw of the country and the war, the more Louis became convinced that his father wasn't doing all that he could to help defend against the repeated English attacks. Despite the relatively recent French victory at Orléans, inspired by the young Joan of Arc, France still had a long way to go in terms of uniting against the common enemies. (France was also at war with Burgundy during this period.) For a handful of reasons, Louis's father, who had been crowned King Charles VII in 1429, had lost the support of several significant nobles. That group of disaffected nobles convinced Louis to join their cause, opposing his father's prosecution of the war. He joined them in open rebellion in 1440. (Charles had named Louis a commander of forces in the Languedoc and in Poitiers in 1439, but the Dauphin wanted more power and his father wouldn't agree.) Part of Louis's enmity toward his father stemmed from the latter's relative indifference to his son's happiness at his wedding, in 1436, to Margaret Stewart, daughter of King James I of Scotland. The king was publicly rude to his son at the royal wedding, opening a wound that son would never allow to heal fully.  French forces continued to advance, taking back Charles easily crushed the rebellion but forgave his son and gave him command of troops in the army and even gave him a seat on the royal council. Things for France were looking up by this time. In 1435, King Charles had convinced Philip III, duke of Burgundy, to switch sides, abandoning his attacks on France, ending an alliance that had held for more than two decades. England and France had achieved a brief truce in 1444, and Henry VI had married the French princess Margaret of Anjou on April 23, 1445, at Titchfield Abbey. England broke the fragile truce four years later by sacking lands in Brittany. France retook Rouen and consolidated its hold on Normandy. France besieged the Gascony capital, Bordeaux, on June 30, 1451, only to lose it the following October. Another French victory followed, at the Battle of Castillon, in July of 1453. That was officially the last battle of the war. England still controlled Calais, but that was the extent of its French possessions. Despite the end of the war, king and Dauphin were still at odds, mainly because Louis had declared his intention to marry again and Charles had refused to grant permission. Louis got married anyway, to Charlotte, the daughter of the Duc of Savoy. An angry Charles led an army to where Louis was staying, forcing his son to flee to Burgundy, where he stayed for the next several years. When Charles died, in July 1461, Louis returned and claimed the throne. King Louis XI presented a dichotomy in appearance and intrigue. He maintained his habit of dressing and traveling simply, yet he embarked on schemes of the highest political order, solidifying the monarchy at the top of the military and leadership order while all the time appearing to be a plain-clothed man of peace and good intent for all. Charles VII had built up a strong standing army, and Louis XI used that to his advantage. He beat back a repeated challenge from Charles, Count of Charolais and also turned back a rebellion attempt by the League of the Public Weal, a consortium of nobles who ended up seeing in their former friend Louis the same kind of enemy that they once saw in his father. Through various nonviolent schemes, Louis secured peace agreements with all of his opponents.

One of his opponents named Louis the "Universal Spider," in reference to the kind of web of intrigue that he also seemed to be spinning. One of those plots involved the overthrow of the King of England, Edward IV. In 1470, Edward was the king, having taken the throne from Henry VI during the Wars of the Roses. Louis joined hands and forces with the Earl of Warwick in handing the throne back to Henry VI. Seeing this, Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy accused Louis of reneging on their peace agreement and led an invasion force into France. The French standing army was more than enough to beat back Charles's attack force, and Charles and Louis again agreed to peace, in April 1473.

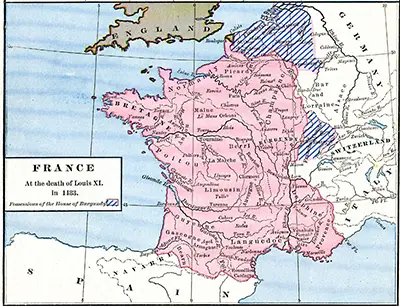

Two years later, England had again invaded France, as Edward IV was once again in charge of the royal army. The English force that landed at Calais was nowhere near enough to worry Louis, and Edward soon sued for peace. Charles the Bold had been harrying French possessions again, and later in 1475, he and Louis agreed to a long-term truce. Louis, at the head of his army, then went on a town-seizing spree, bringing more and more territory into the royal fold. The death of Charles in 1477 convinced Louis that the time was right to annex Burgundy, and a war ensued. The 1482 Treaty of Arras ended the War of the Burgundian Succession, with both Louis and Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I getting some of what they wanted. At the same time, Louis kept tabs on what was going on all around his kingdom. He traveled extensively and also instituted a set of horse couriers, who carried written messages from place to place, sending information back to the king so he could keep his finger on the pulse of his realm. Louis suffered from ill health on and off during the last decade of his life. He suffered two cerebral hemorrhages, once in 1481 and another two years later. The second one killed him, and he died on Aug. 30, 1483. Louis and Charlotte had had eight children, three of whom survived into adulthood; of those, one was a boy, Charles, and he became King Charles VIII. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White