Confederate General Robert E. Lee

Mere days after that victory, Lee, having won Davis's support for an invasion of the North, led his men across the Potomac River, bound for Harpers Ferry. The Union garrison there was only one of Lee's targets. Another was the maintenance of communication and supply lines to the South. Yet another was the state of Maryland, so far still in the Union despite allowing slavery within its borders. Lee also hoped that a Confederate victory in the North would not only demoralize the northern war effort but also convince one or more European nations to recognize the Confederacy as a sovereign nation. Lee dispatched his trusted subordinate Stonewall Jackson and half of the army to Harpers Ferry. Lee and the rest of the army moved toward Hagerstown, Md.

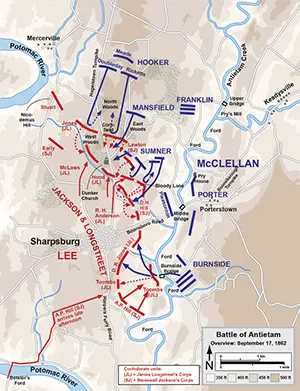

In the North, McClellan (left) was once again in charge, and Lincoln tasked McClellan with defending Washington, D.C., by stopping Lee. McClellan picked up the pieces of the Army of the Potomac, roused his men once more, and marched them off toward the advancing Confederate army. McClellan had an extra advantage up his sleeve. On September 9, 1862, Lee had issued Order No. 191, informing his commanders of the routes that he wanted them to take during the invasion. A member of the Confederate force used a copy of that order to wrap around a handful of cigars, which was inadvertently dropped and later found by Union soldiers from Indiana. Energized by the new information, McClellan set about in pursuit of Lee–although at his usual glacial place, giving the Confederate troops time to advance. However, what the discovery of the orders did do for McClellan, even though Lee eventually discovered that the orders were lost, was give McClellan a destination for his troops: Because he knew where Lee was headed, McClellan could place his troops in the way. The two forces first met at 1,000 feet above sea level, on South Mountain, on September 14. Union troops were successful at breaching the Confederate defenses at three mountain passes–at the cost of 2,500 Union dead and 3,800 Confederate dead–and Lee retreated off the mountain. In the meantime, Jackson had succeeded in his mission, capturing Harpers Ferry and its vital supplies, then hurrying to meet up with Lee, outside Sharpsburg, along Antietam Creek.

Lee's men were there first and so had the opportunity to choose where the fighting would take place. Gen. James Longstreet set up in the center and right; Jackson's men filled the left. They watched as thousands of Union soldiers strode into position along on the east side of the creek. Rains accompanied final preparations, on the night of September 16. At dawn the following day, shots rang out, men charged, bodies fell, and chaos reigned for a full 12 hours. Not for the last time, Lee had managed to convince his Union counterpart–in this case again McClellan–that he was facing many more Confederate troops than were actually on the field of battle. McClellan held back his reserves, anticipating having to use them to fend off a fierce counterattack, and so missed an attack to drive Lee's men from the field of battle. The Battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg was technically a Union victory because Lee and his men retreated back into Virginia. However, casualties were high on both sides. Lincoln, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, and the rest of the Union command team still wanted Union troops to march on Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy in order to seize it and to force Lee and his troops to defend it. The next target for the Army of the Potomac was set as Fredericksburg. However, the first action would be one of deception. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, the new commander of the Army of the Potomac, planned to make it look like his troops were converging on an area southwest of Manassas, then move at great speed to the real target, Fredericksburg. The plan was to keep Lee guessing about the Union army's true target long enough for the Union troops to slip away unnoticed. Union troops marched to the southwest, converging on the town of Fredericksburg, which was south of Washington, D.C, down the Potomac River. The town was on the southern bank of the Rappahannock River, and Union troops would have to cross the river in order to attack the town. Burnside had decided that the way to do this was to use a number of pontoon bridges to ferry his troops across the river. The troops arrived long before the pontoon bridges did, and Burnside and his commanders decided not to risk having their soldiers wade across the river. While the Union troops waited for their pontoon bridges to arrive, Lee and his army, having not taken the bait, converged on Fredericksburg, filling it with Confederate troops. More importantly, they seized the high ground, installing big gun batteries and large numbers of troops on Marye's Heights and Prospect Hill that would be quite defensible as long as the ammunition did not run out. Under pressure from Lincoln and others in the high command, Burnside ordered an assault to begin on Dec. 11, 1862. The first order of business was to assemble the pontoon bridges. Those doing the assembling were soldiers and engineers, who completed their vital task while being subjected to withering enemy fire. Returning fire as much as possible, Union troops provided enough cover to enable the completion of the pontoon bridges, which the troops then used the following day to cross the river, again under hails of gunfire. On December 13, Burnside ordered a full assault all along the line. The Union troops marched across open ground, firing and reloading as they went, with the aim of reaching the high ground and dislodging the defenders. The total number of troops in the Union force for this battle was 120,000; Burnside, who on December 14 had announced his intention to take the field himself and lead yet another charge and had been talked out of it by his commanders, abandoned the assault entirely on December 15, and his troops retreated across the river. At the end of the battle, Union casualties numbered 12,653 (1,284 dead, 9,600 wounded, 1,769 captured or missing) and Confederate casualties numbered 5,377 (608 dead, 4,116 wounded, 653 captured or missing). Lincoln relieved Burnside of his command and replaced him with Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who had led one of the futile assaults on Fredericksburg. Next page > The Heights of Victory and the Depths of Defeat > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Lee's next opponent on the field of battle was another aggressive commander, Union

Lee's next opponent on the field of battle was another aggressive commander, Union  Confederate troops numbered 85,000. However, the defensive positions set up by Lee and Longstreet were nearly impregnable and made it easy enough to continue mowing down advancing Union soldiers.

Confederate troops numbered 85,000. However, the defensive positions set up by Lee and Longstreet were nearly impregnable and made it easy enough to continue mowing down advancing Union soldiers.