The First Battle of Bull Run/Manassas

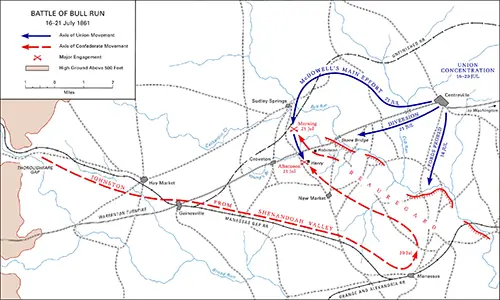

The First Battle of Bull Run, or the First Battle at Manassas, was a great victory for the Confederacy and a source of dread for the Union during the American Civil War. Many sources name the battle Bull Run, after the river of that name; many other sources name the battle Manassas, after the town of that name. Confederate forces under P.G.T. Beauregard had shelled the Union-occupied Fort Sumter on April 21, 1861. Beauregard was one of the Confederate commanders at Bull Run; he had 20,000 men. The other was Joseph Johnston, who had about 12,000 men. After the attack on Fort Sumter, U.S. President Abraham Lincoln had issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to augment the existing force of the Union Army. The new recruits, many of whom had never before served in any sort of military capacity, signed up for a term of three months. That three-month term was ending as the month of July began. Lincoln and others in the War Department wanted those men to fight before their term of enlistment was up. Commanding the two Union armies were Irvin McDowell and Robert Patterson. McDowell's force numbered about 35,000; Patterson was in charge of about 18,000. McDowell was the overall commander and was under pressure to deliver a quick victory for the Union, smashing open the way to Richmond.

McDowell moved his men south, starting on July 16. The intense heat bothered the untrained troops (as did certain temptations like picking blackberries along the way), and it took them a few days to travel the 25 miles from Washington, D.C., to their intended target, Manassas, Va. Waiting there were Beauregard and his men. The battle took place where the Manassas Gap Railroad met the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. The former led to the Shenandoah Valley and to Richmond, the Confederate capital. The first encounter was a reconnaissance mission for the Union, as a small number of men crossed Bull Run at Blackburn's Ford, testing the Confederate defenses. A handful of men died on both sides, and the various commanders (including, on the Confederate side, Gen. James Longstreet) got the information they wanted. With the entirety of his experience as a supply officer and the entirety of experience of his troops very little, McDowell nonetheless drew up a battle plan that, among other things, called for Patterson and his men to attack Johnston and his men, keeping them from supporting Beauregard's force. The plan was a complex one, incorporating a slow-developing feint that never materialized, and proved too difficult for McDowell's raw recruits to execute in a timely manner in the heat of battle. At the same time, the Confederate troops suffered from communication problems, as Beauregard had intended to implement a complex battle plan as well. The two sides threw themselves at each other with little forethought. The Union had more men on the field of battle, and their superior numbers for a time looked to be the difference-maker. However, Patterson's force proved unable to stop Johnston's men from leaving Winchester and linking up with Beauregard's. Another group of troops in the Confederate Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. Theophilus Holmes, was stationed elsewhere in the Shenandoah Valley.

As well, one of the most famous episodes of the war took place on this day, July 21 One of the colonels commanding troops for the Confederacy that day was Gen. Thomas Jackson. He was on Henry House Hill and held off attack after attack by the Union troops. Another commander, Barnard Bee, saw how Jackson, sitting atop his horse, appeared unperturbed at the chaos whirling around him. Hoping to rally his men, Bee shouted at them, "There stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally behind the Virginians!" Jackson thereafter was known as Stonewall Jackson. It was Jackson's men as well who were the first to utter the high-pitched screams that came to be known as the Rebel Yell. A final infantry charge by Col. Jubal Early and cavalry charge led by Col. Jeb Stuart put the Union troops to flight, and the retreat turned into a rout. As it turned out, Beauregard's battle plan had proven too complex for his troops as well, but the fierceness of the Confederate counterattack, the

unyielding example of Stonewall Jackson, and the timely arrival by rail of Johnston's reinforcements had been enough for the outnumbered Confederate Also fleeing the area were the dozens of Northern "observers" who, so assured of a Union victory, had laid out a picnic nearby. The observers included some members of Congress. Appearing just in time to savor the victory was Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Despite the rout, Confederate troops were exhausted and disorganized and could not properly chase the fleeing Union troops. They did, however, seize a large amount of munitions. Casualties for the Union numbered nearly 3,000, including 460 dead. Confederate casualties numbered nearly 2,000, with 387 dead. Also notable for this battle were the contributions of Rose Greenhow, a prominent wealthy Washington, D.C., resident who ran a Confederate spy ring. Thanks to information from Greenhow, Beauregard knew the destination and strength of McDowell's force. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

troops to nonetheless claim victory.

troops to nonetheless claim victory.