The Firing on of Fort Sumter: the Civil War Begins

It was on April 12, 1861, that the first shots in anger were fired in the American Civil War. The target was Fort Sumter, owned by the United States Army but on that day technically still U.S. property but surrounded by land that was part of the Confederate States of America. South Carolina, on Dec. 20, 1860, had become the first state to secede from the Union. Another six states–in order, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas–had followed, and those seven states formed the Confederate States of America on Feb. 8, 1861. So in political terms, Fort Sumter was an island.

The fort itself was one of several dozen forts that made up the Third System, a coastal defense network that Congress put into place beginning in 1817. The placement of the fort on a manmade island made of granite and even its shape–five sides, each of which had three tiers–provided it effective control of Charleston harbor. Charleston had been a stronghold of British forces during the Revolutionary War, and the Continental Army needed a number of expeditions to retake it. A big fort, it could house 650 soldiers and 135 big guns. However, nothing like that was in place in early 1861 because a dispute over harbor ownership had delayed construction.

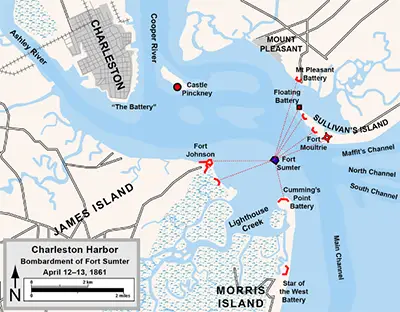

The commander of the Union garrison was Major Robert Anderson (left), who arrived at Fort Sumter only on Nov. 15, 1860. A Kentucky native and onetime slaveholder, Anderson arrived first at Fort Moultrie and set about improving that fort's defenses. The pattern had been for each state that seceded from the Union to take control of federally owned property like forts. Like Fort Sumter, Fort Pickens in Florida was ramping up its defenses, having refused to be occupied by Florida state authorities. Complicating the missions of those fort commanders was that their commander-in-chief, President James Buchanan, had not stood in the way of Southern seizures of federal property. Buchanan feared that such orders would convince other Southern states to leave the Union. Anderson arrived before South Carolina had officially left the Union. When that secession occurred, he ordered his men to abandon Fort Moultrie and take cover inside Fort Sumter. Thus, one of the two Union forts in Charleston was ripe for the taking. The other was an incomplete behemoth of a fortification that was, in reality, a piece of unfinished business. Construction had begun in 1827 and dragged on and on. Buchanan wanted to keep Fort Sumter in the Union orbit and ordered a Union supply ship to rendezvous with the Fort Sumter crew. On Jan. 9 1861, the Star of the West entered the harbor leading up to the fort, and Confederate guns, some of them at Fort Moultrie, fired on the ship. The supply ship made its escape but didn't deliver its supplies.

Anderson and his men held out, protected by their heavy fortifications. Confederate troops occupied positions outside the fort. In March, the Confederate States of American produced a constitution that was a blueprint for a new government. Newly elected Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard (right) to lead the siege. U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, after hearing that Anderson and his men had food for less than two weeks, ordered another relief force to sail to the fort. Lincoln also got in touch with the Governor of South Carolina, Francis Pickens, and told him that the ship would bring food, not weapons, and, further, that if the supply ship was fired on, as the first one had been, then the next relief expedition would contain the means to reinforce the fort.

On April 11, the Confederate government sent a group of men to meet with Fort Sumter commander Anderson, essentially to demand his surrender. Anderson refused to do so. Later that night, Confederate leaders gave Anderson a one-hour warning that they were intending to fire on the fort, and then they did so, starting at 4:30 a.m. on April 12. Firing the first shot was Edmund Ruffin of Virginia. The firing continued intermittently for 34 hours, firing in all more than 3,000 shells. Union troops returned fire intermittently as well, starting with Captain Abner Doubleday, who fired the first shot in defense at 7 a.m. At 2 p.m. on April 13, Anderson agreed to a truce, so his men could vacate the fort. At 2:30 p.m. the following day, he surrendered the fort. During the bombardment, Anderson had instructed his men to take cover as much as they could. As a result, the bombardment killed none of the 68 men defending the fort. Two of his men did die after the shooting had stopped. Anderson won permission to fire off a 100-gun salute to the U.S. flag as a last act of defiance, and a pile of cartridges exploded during this salute and killed two of Anderson's men. The following day, Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to fill the ranks of the Union Army. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White