The Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam was a Union victory during the American Civil War, in the sense that it ended a Southern invasion of the North. Casualties from this one-day battle were very high and are still the highest ever on American soil.

The retreat of the Union army from Manassas for a second time at the end of August 1862 had emboldened Army of Northern Virginia commander Gen. Robert E. Lee (right), so much so that he won the support of his commander-in-chief, Confederate President Jefferson Davis, for an invasion of the North. Mere days after the Second Battle of Bull Run, Lee and his armed force crossed the Potomac River, bound for Harpers Ferry. The Union garrison there was only one of Lee's targets. Another was the maintenance of communication and supply lines to the South. Yet another was the state of Maryland, so far still in the Union despite allowing slavery within its borders. Lee also hoped that a Confederate victory in the North would not only demoralize the northern war effort but also convince one or more European nations to recognize the Confederacy as a sovereign nation. Lee dispatched his trusted subordinate Stonewall Jackson and half of the army to Harpers Ferry. Lee and the rest of the army moved toward Hagerstown, Md.

In the North, Gen. George McClellan (left) was once again in charge, and President Abraham Lincoln tasked McClellan with defending Washington, D.C., by stopping Lee. McClellan picked up the pieces of the Army of the Potomac, roused his men once more, and marched them off toward the advancing Confederate army. McClellan had an extra advantage up his sleeve. On September 9, 1862, Lee had issued Order No. 191, informing his commanders of the routes that he wanted them to take during the invasion. A member of the Confederate force used a copy of that order to wrap around a handful of cigars, which was inadvertently dropped and later found by Union soldiers from Indiana. Energized by the new information, McClellan set about in pursuit of Lee–although at his usual glacial place, giving the Confederate troops time to advance. However, what the discovery of the orders did do for McClellan, even though Lee eventually discovered that the orders were lost, was give McClellan a destination for his troops: Because he knew where Lee was headed, McClellan could place his troops in the way. The two forces first met at 1,000 feet above sea level, on South Mountain, on September 14. Union troops were successful at breaching the Confederate defenses at three mountain passes–at the cost of 2,500 Union dead and 3,100 Confederate dead–and Lee retreated off the mountain. In the meantime, Jackson had succeeded in his mission, capturing Harpers Ferry and its vital supplies, then hurrying to meet up with Lee, outside Sharpsburg, along Antietam Creek.

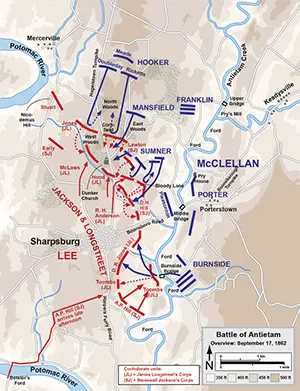

Lee's men were there first and so had the opportunity to choose where the fighting would take place. Gen. James Longstreet set up in the center and right; Jackson's men filled the left. They watched as thousands of Union soldiers strode into position along on the east side of the creek. Rains accompanied final preparations, on the night of September 16. At dawn the following day, shots rang out, men charged, bodies fell, and chaos reigned for a full 12 hours. Union forces made three major attacks on Jackson's men on the Confederate left, on the Sunken Road. Leading the first attack was Gen. Joseph Hooker; the second attack commander was Gen. Joseph Mansfield; then came the men reporting to Gen. Edwin Sumner. None of those three major attacks, savage and unrelenting as they were, forced the defenders to break ground and flee.

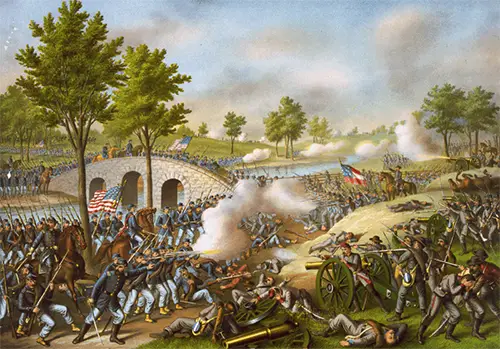

Attacking the Confederate right were men under Gen. Ambrose Burnside, who battled for three hours to take a vital bridge and then, for some reason, delayed a further attack; by the time that Burnside's men advanced again, reinforcements in the form of General A.P. Hill's men had arrived from Harpers Ferry and plugged the gap in the line. McClellan's plan was for the attacks on the left and the right to drive those men back, so a strong attack could be made on the center. The fierce Confederate defense prevented this from happening, and McClellan held back a sizable force from the fray; the reserves were intended to force the issue in the center. Thus, total numbers committed on both sides were roughly equal. Union troops at the beginning of the battle numbered 87,000; Confederate troops at the beginning of the battle numbered 45,000. As had already happened, McClellan was convinced that Lee had more troops than he actually did. As well, McClellan hadn't shared his entire battle plan with his commanders, so each had to operate within his own sphere of influence. At places like Dunker Church and West Woods and East Woods and the Cornfield, men died by the hundreds. One of those was Brig. Gen. J.K.F. Mansfield, at 59 the oldest general in the Union army. The two armies fought each other to a standstill, as darkness ended the fighting. Confederate casualties were large: 9,298 killed or wounded. The total convinced Lee to retreat back across the Potomac, to the relatively safe haven of Virginia. The troops moved on the evening of September 18, the day following the battle; during this second day, very little took place, as both sides exhaustedly retrieved their dead. Union casualties were larger: 11,648 killed or wounded. By the rules of warfare, the Union army won the Battle of Antietam/Sharpsburg. Lee's retreat was a ceding of the struggle. McClellan chose not to pursue. Lincoln considered it enough of a victory to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, abolishing slavery in the Southern states, four days later. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White