The Battle of Harpers Ferry

The Battle of Harpers Ferry was a resounding victory for Confederate forces during the American Civil War. The Potomac River and the Shenandoah River met at the Virginia town, site of a Union arsenal. The arsenal had been the target of an assault in 1859 by noted abolitionist John Brown; that attempted seizure of the weapons and ammunition at the garrison had been unsuccessful, and Brown had been captured by a military contingent led by Robert E. Lee. Now, Lee, at the head of a Confederate army, wanted to take the weapons and ammunition for himself. Flush with victory for a second time at Manassas, an emboldened Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac near Leesburg in early September 1862 and headed in a few different directions. Troops under Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson marched to Martinsburg, to seize the Union arsenal there, and then to go to Harpers Ferry, site of a much larger Union arsenal, where another set of troops would go. Meanwhile, Lee and the main army moved into Maryland and awaited the return of the men who were to take the arsenals. Jackson and his men entered Martinsburg on September 12, 1862, and took it without firing a shot. The Union commander there, Gen. Julius White, had heard of the Confederate advance and had ordered his men to Harpers Ferry. Commanding the garrison at Harpers Ferry in the fall of 1862 was Col. Dixon Miles, who had orders from his commander, Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, to hold the city, despite an urgent call from Gen. George McClellan to have the Harpers Ferry troops join the Army of the Potomac. Confederate troops had burned much of the town in 1861, and what remained was almost entirely military in nature–barracks, stables, hospitals. The town was still a key part of the Union supply line, protecting both the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal.

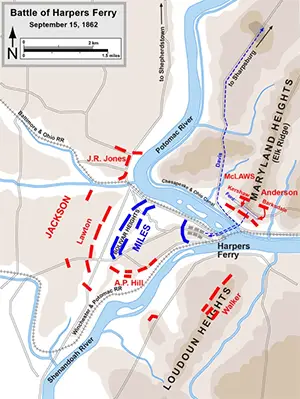

The town of Harpers Ferry was ringed by hills, and whichever army controlled those hills could control the town. As would be the case in most instances during the war, the holders of the high ground had a decided advantage. Miles had 12,000 men, whom he divided into four brigades. A sizable part of that force went to Bolivar Heights, two miles west of Harpers Ferry. Smaller forces went atop Camp Hill and Maryland Heights; in both cases, those soldiers had seen little or no combat. The remaining high ground, Loudoun Heights, was 1,200 feet up and very steep; Miles, a veteran of the Mexican-American War, was of the considered opinion that Jackson and his men would not attempt such a daunting feat. The bulk of the Union troops were in the town, on the low ground. On September 12, the Confederate attack began with the seizing of Maryland Heights; once Gen. Lafayette McLaws had taken the hill, his men installed artillery on it. Other Confederate brigades overwhelmed the overmatched defenders on Bolivar Heights and Camp Hill. To Loudoun Heights went the brigade of Gen. John Walker, who encountered no resistance as they seized the very high ground. Miles, the Union commander, wrote desperately to his overall commander, Halleck, asking for reinforcements. On the morning of September 13, the Confederate batteries opened fire while infantry converged on Union positions. Jackson and the rest of the Confederate force arrived that evening. After another day of maneuvering and a few skirmishes, all was set for a furious assault on September 15. Early that morning, Jackson's artillery, ensconced on the heights surrounding the town, tore the Union defense to shreds; Union troops took cover in ravines and behind trees. The big Union guns ran out of ammunition; and Confederate Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill, recently reinstated after being put under arrest for being late to a battle, readied an all-out assault on the town. Union Gen. Julius White had arrived from Martinsburg and had taken over for Miles, who had been mortally wounded in the firefight. White it was who signaled the surrender. The victorious Confederates claimed 13,000 guns and 73 pieces of artillery, along with 11,500 captured Union soldiers. The only Union troops to escape were about 1,300 members of Col. Benjamin Franklin Davis's cavalry, who had taken off on assignment the night before and eventually ended up with McClellan's force near Sharpsburg. Also arriving at that battle at Sharpsburg was the much larger division of A.P. Hill. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White