Napoleon Bonaparte: Giant of the Age

Part 10: Disaster in Russia On June 23, the Grand Armée crossed over the Niemen River and into Russia. Even by this point, a month into the expedition, they were starting to run short on supplies, even though the supply network was extensive and well provisioned, stretching all along the corridor of travel. Four days later, they captured the city of Vilna and found that nothing much remained of value in the city. The Russian army had slipped away, leaving little to conquer. That night, the invaders suffered through an unseasonable storm of hail and sleet. Such weather muddied whatever sparse roads existed in that part of the country, forcing draft animals and transport wagons to proceed even more slowly than normal. Blazing summer heat followed unseasonal storms, hardening ruts created by heavy wagons and stalling the progress of those wagons and the soldiers who needed what was in those wagons. As a result, infantry traveled much more quickly than the artillery that they hoped to use in battle and the supplies that they needed to fight those battles and to survive afterward. The vaunted Napoleonic strategies of lightning fast marches and turn-on-a-dime pivots to confront and surprise a new enemy that had worked so well in previous wars could not be employed in the wastelands of western Russia. It was all well and good that Warsaw contained a very large arsenal of guns, gunpowder, and cannons; it was little good to an army whose method of transport depended on simple things like dry dirt on which a wagon's wheels could safely operate. Such wagons went much more quickly on the paved roads of Western and Central Europe. Even worse for the French, a sudden storm had resulted in the deaths or otherwise loss of 10,000 horses.

As the invasion force pressed on in search of a military victory, the defenders kept on retreating, abandoning Vitebsk and then, significantly, Smolensk, burning buildings, munitions stores, and (perhaps most importantly to the French at this point) crops as they fled. At the very edge of French-controlled territory were abundant stores of food, water, and medical supplies; none of that could be transported to an army that was being pulled away to the east more quickly than anticipated. It was the middle of summer at this point, and problems with water supply for the Grand Armée resulted in soldiers' drinking unsafe water and getting dysentery. Many also succumbed to typhoid fever, borne by insects living in swamps. Others had struggled in the summer heat to carry their excess food and had discarded it. Still others deserted; as the campaign wore on, those numbers skyrocketed. As well, deserters sought comforts in the possession of whatever little local population remained in the wake of the passage of the large armies, creating havoc that interfered with French lines of supply. The French force had taken some time at Vitebsk, to rest and await the arrival of supplies and reinforcements. The preference of the emperor and all of his commanders was to spend the rest of the year there and continue the invasion in the spring. At his most optimistic, Bonaparte had, if the war was still on, planned to be as far east as Smolensk before stopping the campaign for the winter, thinking to spend the cold months behind the lines. Now that they had advanced so far, he decided to go farther, overriding the will of his commanders and succeeding in convincing them to continue the fight. One of the main factors in doing this was the knowledge that delaying the invasion by a handful of months would give both sides the opportunity to add reinforcements. Bonaparte knew that his ability to do this would be more difficult than Russia's, and he also knew that such a sustained absence from Paris might encourage an insurrection, especially because the guerrilla wars in Spain showed no signs of easing.

When French troops entered Moscow on September 14, they found it on fire. Most of the residents of that large and historic city had fled, taking much of their food and belongings with them. They left behind large amounts of hard liquor, and despondent French soldiers helped themselves to that, increasing the devastation of the looting that resulted from frustration. The fleeing Russians had also taken all firefighting equipment with them as they fled, so the fires burned and burned. Napoleon watched helplessly from the Kremlin as his dream of gaining Alexander's surrender hung in the balance.

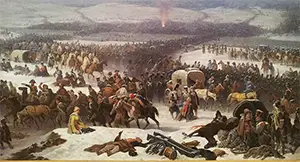

Travel was slow at the best of times in that part of Russia, and it was even slower as winter set in. Initial calculations were that it would take the slowest elements of the French army 50 days to reach friendly territory.

The Russian army did not waste opportunities to harry the French movement. Bonaparte leaked supposed battle plans that called for further assaults elsewhere, but the main army headed back to Smolensk, along the way inexplicably wasting a week's travel in the harsh winter by retracing their steps and marching their way into a major battle just cross the Berezina River. The French army reached Smolensk on November 9, hoping to find the major supply depot intact. It was not, having been the victim of looting by the rear of the army, which had promptly turned around at the first orders of retreat. A frustrated, starving army looted the city and consumed the remaining rations at a frightening rate, in less than a week, eliminating what should have lasted two weeks. By this point, even more of the French force had been lost, through a combination of death, injury, and desertion. Not long afterward, Russian troops took control of Minsk, where the French army had left 2 million rations. Then came two bits of goods news for Bonaparte. First was the reappearance of Marshal Michel Ney, who was thought to have been captured but had escaped with a fraction of his force across the frozen Dnieper River and fought his way back to what was left of the Grand Armée. It was at the end of November that the other piece of luck came France's way. A series of well timed maneuvers and the success of a diversion enabled the surviving French troops to not only cross the Berezina River–which, because of a sudden warm spell, had thawed enough to allow crossings–but also to escape the Russian army and move westward. By this time, the Russian forces were depleted and/or exhausted as well, and Kutuzov chose not to pursue the French. Bonaparte and his surviving commanders had a council of war at Smorgoni on December 5. All agreed that the emperor should go ahead of the army and return to Paris with all possible speed. Left in charge of the army was Marshal Joachim Murat. During the next three days, the army suffered through the coldest temperatures yet. They were ill equipped for such travel in such weather, and 20,000 died en route to Vilna. The rest reached their destination on December 8 and, despite Murat's orders to the contrary, set about looting the city.

Murat was supposed to stay in Vilna and recover, but the looting convinced him to do otherwise and he ordered a further march. Two days later, the army struggled with the frozen hill of Ponarskaia, which most of the horses could not traverse. The troops staggered on, also leaving behind their few remaining guns and the royal treasury, which at that point still numbered 10 million francs. The men soldiered on, reduced to what they themselves could carry. They limped across the Niemen on December 14. Of the more than 650,000 soldiers who had marched with their emperor on the invasion of Russia, only 93,000 returned home. Russian troops captured a full 200,000 French soldiers. The other losses, numbering 370,000, were due to battle deaths and injuries or exposure to the deadly weather and/or diseases. Also of supreme significance for the later of the Napoleonic Wars, the French army had lost 200,000 horses. Next page > The Allies Triumph > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

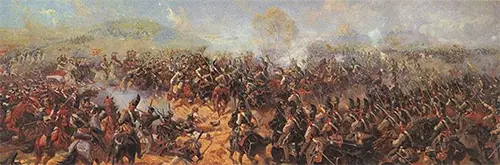

Bonaparte's looked-for great battle finally took place

Bonaparte's looked-for great battle finally took place  Bonaparte settled in Moscow and awaited for a message of surrender or at least discussion from Alexander. None came. By this time, the strength of the Grand Armée had greatly diminished, with troop numbers there fewer than 100,000. (About the same amount littered the Russian countryside along the way from Poland to Moscow.) Alexander was ensconced at St. Petersburg, and communications at that time of year through normal networks took a week in each direction. The tsar knew that Kutuzov had about 110,000 men just in the vicinity of Moscow and more scattered around the country. Napoleon waited a month without hearing from the tsar before deciding to leave. On October 19, French troops left the Russian capital, headed southwest–ostensibly back the way they came but on a different road, seeking different results.

Bonaparte settled in Moscow and awaited for a message of surrender or at least discussion from Alexander. None came. By this time, the strength of the Grand Armée had greatly diminished, with troop numbers there fewer than 100,000. (About the same amount littered the Russian countryside along the way from Poland to Moscow.) Alexander was ensconced at St. Petersburg, and communications at that time of year through normal networks took a week in each direction. The tsar knew that Kutuzov had about 110,000 men just in the vicinity of Moscow and more scattered around the country. Napoleon waited a month without hearing from the tsar before deciding to leave. On October 19, French troops left the Russian capital, headed southwest–ostensibly back the way they came but on a different road, seeking different results.