Napoleon Bonaparte: Giant of the Age

Part 3: War in the Middle East and Another New Government

French troops marching from Alexandria to Cairo encountered a large force of Mameluks and the army of the Ottoman Empire, about four miles from the capital and nine miles from the Pyramids. The forces were evenly matched in terms of overall strength, with France having 20,000 men in total and the Mameluks having a total of 21,000 soldiers; however, the Mameluks had twice as many cavalry, numbering 6,000, and their cavalry was known for their overwhelming success. Bonaparte deployed much of his infantry in a formation known as the Infantry Square, a tactic dating to Roman times that involved infantry forming in a square in order to counter the effects of a cavalry charge. In this case, the French deployed cannons at the corners of the squares. The idea was to wait until the horses were close enough and then fire. The French squares executed the strategy well enough to prevent more than one cavalry charge. The rest of the French force attacked the enemy in the nearby village of Embabeh. Trapped between French attackers and the Nile, a number of Mameluks and Ottomans tried to swim across the river; hundreds of them drowned. The defeat inflicted on the losing force nearly complete demolition, in combined deaths and injuries. French troops, meanwhile, suffered 29 deaths and more than 250 wounded.

All of that seemed for naught on August 1, when the British fleet under Admiral Horatio Nelson savaged the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile. Despite fairly even numbers, the British ships fared far better in the battle not far from Alexandria, sinking the French flagship L'Orient and several others. French dead included the overall naval commander, Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys. The British victory cast doubt on French invincibility and played a part in some other European nations' banding together again to fight revolutionary France. Thus began the War of the Second Coalition. Napoleon, meanwhile, and his army were trapped in the Middle East. He set about taking over Egypt, reorganizing its administration along the lines of Western institutions. It wasn't long before Turkey declared war on France. To forestall a full-blown invasion by Turkish forces, the French army in February 1799 marched into Syria. They traveled up the coast, conquering the ancient towns of Gaza, Haifa, and Jaffa. At Acre, they found defeat at the hands of the British-Turkish force there and distress at the hands of the plague, which had struck the French army. A frustrated Bonaparte ordered a return to Egypt. On July 25, 1799, he fought off an Ottoman invasion of Alexandria. A month later, Bonaparte sailed for home. By this time, France had reversed the losing trend that it had exhibited at the beginning of the War of the Second Coalition. However, the country as a whole and Paris in particular were in a state of uncertainty. Especially troubling was the political situation in the capital and in the government itself. The Councils called for a forced loan of a large sum of money, in order to finance the ongoing war effort and to keep the government finances afloat; as well, the Councils called for a new round of conscription, the first since 1793.

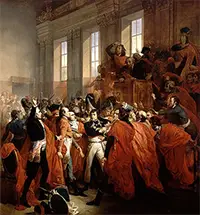

The end of the Directory came in 1799, as the result of the Coup of 18 Brumaire. Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (right), a leader of the Revolution from as far back as the late 1780s, won election to the Directory. He then overthrew the government, although things didn't go exactly as planned. The plan was to initiate a takeover by devious means, by inventing a conspiracy and then tricking the government into handing over the reins in time of crisis. Helping execute the plan were to be Joseph Fouché, the Minister of Police; Pierre François Réal, the Commissioner of the Directory; Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand; and Lucien Bonaparte, who was a brother of Napoleon and who was also the head of the Council of Five Hundred. The plan was for three of the five Directors to suddenly resign, leaving the government with no functioning executive arm. Then, the Councils would hear of an alleged conspiracy that necessitated the movement of the deputies to a safe location a few miles outside Paris. Because it would be a time of war, since the republic was threatened from within, the Councils would be dissolved and a handful of deputies would set about writing a new Constitution. This was a pattern that had been followed in recent years. The coup plotters brought the army in on the deal, and Fouché was to ensure that the police did their part. Also playing a part would be Napoleon himself.

On November 9, deputies in the Council of Ancients heard of the alleged conspiracy at an emergency meeting, at which they agreed to meet the following day at the Château de Saint-Cloud. They also assented to allowing Napoleon to assume command of troops in Paris. A few hours later, the same set of events occurred at a meeting of the Council of Five Hundred, with the same result. Troops then arrested two prominent Jacobin directors, in keeping with the story that it was a Jacobin plot to take over the government. The following day, the Councils met separately, with Napoleon speaking to each group. The Council of Ancient offered no opposition. The Council of Five Hundred did, but only for a time, in the form of harsh verbal resistance from a handful of Jacobin deputies. In the end, after soldiers had intervened and removed the agitators, the lower chamber reconvened and approved the formation of a new government, by way of the Constitution of Year Ⅷ. In this case, the government was the Consulate, which placed maximum power in the hands of a very few. This, many historians say, was the end of the French Revolution. Next page > First Consul to Emperor > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

After his success in Italy, Bonaparte found himself in demand elsewhere. Recalled to Paris, he began planning an invasion of Britain. That never materialized, mainly because he was of the firm opinion that such a plan could never work so long as British forces controlled the high seas. Instead, he led troops against British interests in the Middle East. Bonaparte and 35,000 soldiers, aboard 200 ships, sailed for Egypt. They captured Malta (home to the remnants of the

After his success in Italy, Bonaparte found himself in demand elsewhere. Recalled to Paris, he began planning an invasion of Britain. That never materialized, mainly because he was of the firm opinion that such a plan could never work so long as British forces controlled the high seas. Instead, he led troops against British interests in the Middle East. Bonaparte and 35,000 soldiers, aboard 200 ships, sailed for Egypt. They captured Malta (home to the remnants of the