The Battle of Borodino

The Battle of Borodino was one of the fiercest battles of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle, which took place during France's invasion of Russia in 1812, was a French victory that came at great cost. French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte had decided to invade Russia in order to punish it and its leader, Tsar Alexander I, for their recalcitrance in abandoning the Treaty of Tilsit, signed by both leaders in 1807 and the Congress of Erfurt, agreed to the following year. Both of those agreements brought France and Russia as allies, ostensibly in opposition to the United Kingdom, which had France's most implacable ally for decades. A series of military and political events had convinced Alexander to abandon the alliance with France and, ultimately throw in his lot with the U.K. The response from Napoleon was to assemble the largest army yet seen in Europe and send it eastward.

The plan was to confront the Russian armies, achieve a great victory, and convince Alexander to sue for peace and return to the kind of arrangement that the two leaders had crafted at Tilsit in 1807. Time and again, however, the Russians did not do what was expected. On June 23, 1812, the Grand Armée crossed over the Niemen River and into Russia. Even by this point, a month into the expedition, they were starting to run short on supplies, even though the supply network was extensive and well provisioned, stretching all along the corridor of travel.

At the time, the Russian army was split into two main forces, one on either side of the Pripet Marshes. To the south was Pyotr Bagration, and to the north was Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly; combined, their forces numbered fewer than 500,000. To the north were Moscow and possibly St. Petersburg; to the north was also colder climates. To the south were Kiev and warmer climates; attacking to the south would also mean a longer route to Moscow. Bonaparte decided to attack north of the Pripet Marshes and aim to prevent the two Russian forces from meeting up. The French Army had other enemies at this point, namely typhus, which killed tens of thousands of French soldiers quickly and more efficiently than did Russian bullets and cannonballs. As well, the fast marches of the French troops outstripped the pace of the supply trains, and French soldiers turned to questionable sources of water, resulting in plentiful cases of dysentery. Another strategy that Russia employed with great success in the wake of France's grand invasion was one of withdrawal and destruction. Echoing the strategy employed by Peter I against Sweden's Charles XII a century earlier, the Russian forces did their best to stay one step ahead of the French invaders and also employed a scorched earth policy–burning and otherwise devastating the countryside, farms, towns, and anything else that the French Army could have used as supplies. However, after Bonaparte disregarded his commanders' counsel to stop for the winter, the French Army caught up with the northern Russian force, near the town of Borodino. A fierce battle occurred on September 7. Commanding the Russian force in that battle was Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov, a veteran of previous battles against France; he had replaced Barclay de Tolly as commander in the north.

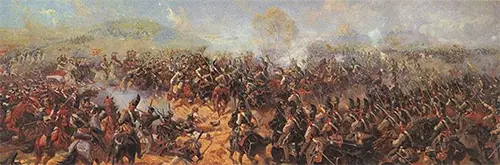

The French force that fought against Russian troops was the main part of the Grand Armée, but it was not all of it. Bonaparte employed a force that numbered between 100,000 and 200,000. (Sources differ on the exact numbers, for both armies.) The Russians countered with a force that was slightly less. Kutuzov chose the land on which the attack would happen. On the right was the Kalatsha River. A series of small streams ran through the area, linking the river with the nearby town of Borodino. Russian artillery and sharpshooters assumed the high ground, including a hill to the southeast that came to be known as the Great Redoubt. On this hill, also known as the Raevsky Redoubt, the Russian placed 19 big guns. Nearby were a series of fortifications known as fléches, which were arrow- or square-shaped earthworks that provided cover for riflemen. Holding down the front of the defense works was the Shevardino Redoubt. The battle occurred during three days. On the first, September 5, the French and Russian cavalries came to blows; the result was a Russian pull-back. The next day, French forces launched a large assault on the Shevardino Redoubt and seized it.

On September 7, Bonaparte ordered a series of frontal assaults, having rejected a plan by two of his commanders to attempt a daring flanking maneuver. First came attacks on the fléches. After a fierce artillery bombardment, French infantry stormed in and briefly gained a commanding position, only to be driven back by a Russian counterattack. Such was the pattern throughout the day. The first shots came at 6 a.m., when French opened up 102 guns with a barrage against the very center of the Russian deployment. Marshal Michel Ney's force was successful at driving defenders from their perches in the fléches. By 2 p.m., French troops had taken the Raevsky Redoubt. However, Bonaparte decided against committing the Imperial Guard, preferring to hold them in reserve. He was convinced that he could win the battle with them, and he wanted them intact for future engagements. He was proved correct when the Russian forces departed the battlefield. It had been a costly victory. Estimates of French casualties ranged from 30,000 to 35,000. Russian losses were higher and included Bagration, but the Russian commanders could more easily lay their hands on reinforcements. The Grand Armée, on the other hand, was all on its own. Bonaparte chose not to pursue the retreating Russian troops, instead moving on to Moscow. A week after the victory at Borodino, French troops claimed the Russian capital. To their dismay, they found it in flames. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White