The Roman Republic

Part 4: The End of the Republic During the Second Punic War, Rome fought also against Philip V of Macedonia. The Romans were largely ineffective at confronting Philip directly but did succeed in keeping him from aiding Hannibal, which played a part in the larger arc that saw the Romans defeat the Carthaginian general in the end. Rome fought three more wars against Macedonia, with the end result being the Roman annexation of Macedonia and its division into two provinces. Roman forces were also victorious against the Seleucid Empire and eventually conquered Greece as well, in 146 B.C. In the following decade, two brothers, Gaius and Tiberius Gracchus, served as tribunes and attempted to achieve more of a representative government by way of land reform. They were rewarded for their efforts by way of persecution and death.

Rome continued its policy of expansion, extending again into North Africa and conquering Numidia. The victorious general in that conflict, Gaius Marius, dominated Roman politics for the next few decades. He led Roman troops to victory during the Social War, against former allies in Italy, then had a falling out with another ambitious commander, Sulla, over who should lead the fight against King Mithridates VI of Pontus. Sulla, at the head of his army, invaded Rome, had Marius declared an enemy of the state, then had himself elected dictator. He took firm control in Rome and ruled with an iron fist for a handful of years. Two allies of Sulla, Crassus and Pompey, were the powers in Rome after Sulla's death. Crassus made a name for himself by becoming the richest man in Rome and also by being the commander who finally put down the slave revolt of Spartacus. Pompey proved a brilliant warrior and tactician and won many battles in the east, bringing glory and money to Rome.

A third powerful leader emerged at this time. Julius Caesar proved himself to be a successful warrior, lawyer, public speaker, and government official. He and Crassus and Pompey were the three most powerful men in Rome and agreed to rule it together as the First Triumvirate. The men became jealous of one another and set off in different directions in order to achieve more conquests for Rome. Caesar went to Gaul and subjugated it (while also making two trips to Britain). Crassus led an army in an invasion of Parthia and was killed there in combat. Pompey emerged as the sole consul in Rome and then agreed to fight Caesar when the latter crossed the Rubicon at the head of an army, in violation of Roman tradition. Caesar emerged victorious in the civil war, forcing Pompey to fleet to Egypt, where he was killed. Caesar ruled Rome alone. He was made dictator for life, an action that made many people fear that he was going to be named king. For hundreds of years, Romans had feared the return of a king, since they had such bad memories of the last king, Tarquin Superbus, the last of the seven ancient kings of Rome. A band of Senators killed Caesar.

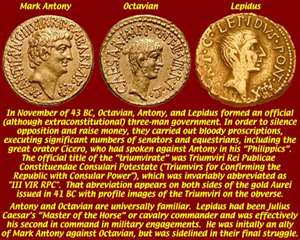

Marc Antony, Caesar's chief supporter, emerged as a powerful force in Rome and, along with the powerful deputy dictator Lepidus and Caesar's adopted son, Octavian, formed the Second Triumvirate. Jealousies flared among these three rulers as well, particularly after Antony became involved with Egypt's pharaoh, Cleopatra. Lepidus tried to steal Octavian's legions and found himself ousted from power. Antony and Octavian then fought each other, with Octavian's victory at the Battle of Actium being the death knell for Antony. Octavian then took sole control. He ended the Roman Republic when he took the name Augustus and became Rome's first Emperor. First page > The Early Years > Page 1, 2, 3, 4 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White