The Roman Republic

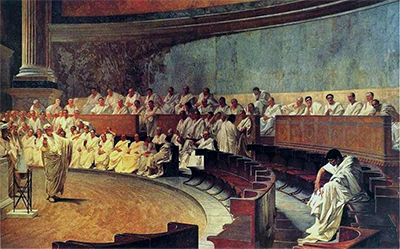

Part 2: The Senate By far the most well-known aspect of Roman government was the Senate, which dated to the founding of the city, in 753 B.C. The Senate elected some of Rome's kings and served as the king's advisors. The word Senate comes from senex, a Latin word that translated into English most closely as "old man"; the idea was that the Senate as an assembly of elders. Romulus, the founder and first king of Rome, chose 100 men to form the first Senate. Their descendants populated the patrician class. The fifth king of Rome, known as Tarquin the Elder, added another 100 men to the Senate. His grandson, Tarquin the Proud, dispatched many of those and didn't replenish the numbers. The first Roman consuls, Lucius Junius Brutus and Publius Valerius Publicola, increased the Senate membership to 300. In later years, the number of Senators went as high as 500.

Senators could spend the rest of their lives in office, unless removed for misconduct. Being a Senator didn't command a salary but did take up a lot of time; this was another barrier to men (for women were not permitted in the Senate) who otherwise had to spend their days working for a living. Technically, the Senate didn't have true legislative power. All potential laws approved by the Senate had to also be approved by either the Centuriate Assembly (over which the consuls presided), depending on which jurisdiction oversaw the aspect of life covered by the proposed law. Senate meetings had to take place within the city boundary or, at the most, within one kilometer (.62 miles) outside it. Before each meeting began, religious officials would perform a sacrifice to the gods and then seek divine omens. The presiding magistrate would then declare the meeting in session and after, giving a speech, direct the Senators to discuss any number of issues. Each Senator could speak on any issue, for as long as he wanted, and every Senator had to be given the chance to speak before a vote could be taken. Meetings began at dawn and had to end at nightfall, so a Senator who wanted to ensure that a vote wouldn't be taken on a certain issue could just keep talking. (This is the origin of the filibuster found in the U.S. Senate.) The Senate (or a consul) could, in times of emergency, appoint a dictator, who would have full powers of consulship for six months. The Senate reserved the right to veto any decision made by a dictator. Such officials were not unknown during the first few centuries of the Republic (with Camillus being the most famous); however, after 202 B.C., the function of the dictator fell instead to the consuls, by way of an "ultimate decree of the Senate." (Before the end of the Republic, the Senate appointed just two more dictators: Sulla and Julius Caesar. Next page > Wars and More Wars > Page 1, 2, 3, 4 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White