Sulla: Ancient Roman Warrior and Dictator

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix, known as Sulla, was a successful general and lawmaker during the Roman Republic. He is known for marching on Rome at the head of his legions and serving as dictator for a year.

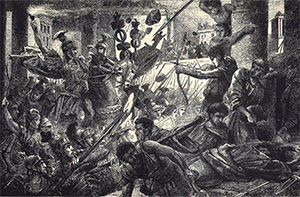

He was born in 138 B.C. into a patrician family. Despite a later period of being penniless, he set about working his away up the political ladder, achieving election to the posts of quaestor, praetor, and consul. Sulla served as quaestor to Garius Marius in the war against the Numidian king Jugurtha. As Rome was closing out its victory over the Numidians, Sulla saw an opportunity to make a name for himself and took it, arranging to be the one who oversaw the surrender. This would be one of a series of events that punctuated an enmity between the two men; they were also part of larger struggle between the Optimates, those who fought to keep the Senate supreme, and the Populares, those who wanted to enact reforms on behalf of the public at large. Marius, as the head commander, enjoyed the success and the spoils, riding at the head of the triumph that followed. A couple of year later, Marius rode northward, again to confront the enemies of Rome. Sulla went with the army, which won great victories against a barbarian force. The Cimbri had gained an ally in the Teutones, and the two armies planned to hit Rome from both north and south at the same time. Anticipating this, Marius moved quickly and checked the Teutone advance at Aquae Sextiae in 102 B.C. Despite the sudden appearance of another army, that of the Ambrones, Marius and the Romans were successful. Marius turned his full firepower on the Cimbri and scored a knockout blow at Vercellae in 101 B.C., resulting in 60,000 Cimbri dead and many, many captured. Marius again served and consul, and Sulla found positions of power elsewhere, including that of proconsul in Cilicia. Pressed back into duty during the Social War of 91 B.C., Marius led troops into victory against Rome's Italian allies, who had had enough of Roman hegemony. Whether through his own bouts with illness or his struggles against political enemies, he retired from the campaign after a year of fighting. The last remaining foe was King Mithridates VI of Pontus. Marius wanted to come out of retirement and lead the legions of Rome against this new threat; however, Sulla, got himself named as commander and set off to do battle with Mithridates and his army. Marius insisted on taking the command and talked the tribune Sulpicius into convincing the Roman people to take the command away from Sulla and give it to Marius. An enraged Sulla returned to Rome at the head of the army, which at the time numbered about 30,000, and forced Marius to flee. Just to make sure that that sort of thing didn't happen again, Sulla, who had taken control of the government, declared Marius an enemy of the state and ordered him to be found and executed. Marius hid out in the hinterlands for a few years, even going to Africa at one stage, there to raise an army to lead back to Rome. Sulla, meanwhile, marched at the head of the legions, again to confront Mithridates. He was successful in defeating the King of Pontus, and his troops also put down a rebellion in Greece. Sulla gave his victorious soldiers free reign to plunder Athens, and some of them damaged the Acropolis and other historic sites. Sulla and his soldiers stayed in the east for a few years. In the meantime, Marius had found his way back to Rome. Intervening in a war between the consuls Cinna and Octavius, Marius made an ally of Cinna and then, once they had dispatched Octavius, set about dispatching their political enemies, without so much as a trial to examine whatever charges they faced. Deaths numbered in the dozens. Marius died in 86 B.C.

Sulla returned to Rome in 83 B.C. and, allied with a trio of commanders–Crassus, Pompey, and Metellus Pius–, eliminated all known supporters of Marius. Sulla's victory in the Battle at the Colline Gate in 82 B.C. ended the civil war. Deaths numbers in the thousands, and the commanders ordered many of the dead thrown into the River Tiber. The Senate named Sulla dictator, an office that had not been filled since the Second Punic War. One of Sulla's dictations, as it were, was to exhume the ashes of Marius and have them thrown into the Tiber. He then ordered the seizure of property of many people who were deemed outlaws by the state. It is at this time that Sulla added the title "Felix" to the end of this name; the word was thought to mean "fortunate one." Indeed, he found favor in most of his battles, within Rome and without. As dictator, Sulla was, in effect, the head of government, able to make new laws and repeal existing ones. He limited the veto power of tribunes and increased membership in the Senate, in part by permitting quaestors to be Senators. He also spent state funds on reconstruction projects, including the Temple of Jupiter and the Senate house itself. He rewarded army veterans by giving them land in Campania and Etruria. He ended his dictatorship in 81 B.C. and was elected consul the following year. At the end of that term, Sulla left government for good in 79 B.C. He died at his Puteoli villa one year later, just after finishing his memoirs. He had had five wives and five children.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White