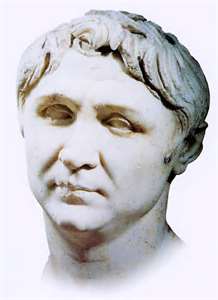

Pompey the Great

Marcus Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, more well-known as Pompey the Great, was one of the greatest military generals in Roman history. He could boast of triumphs throughout the Roman world, on the field of battle and in the halls of government. He rose to the very heights of political will but ultimately met defeat and treachery. Born into a wealthy Italian family, Pompey showed early acumen in warfare by throwing in his lot with Sulla in his struggle with Gaius Marius. Pompey conquered Sicily in 82 B.C., the year that Sulla was declared dictator, then moved on and solidified Roman influence in Africa. Sulla rewarded Pompey for his service by giving him the title Magnus ("the Great").

Crassus and Pompey were two of the most powerful men in Rome at the time, yet they were not allies. They shared a mistrust of each other that only grew in the year that they served as consuls. The year before, Pompey had captured some stragglers from Spartacus's slave revolt (ended by Crassus) and then claimed credit for ending the revolt himself. Each of the two men was suspicious of the other's ambitions as well. The following year, the Senate called on Pompey again to lead Roman forces against King Mithridates VI of Pontus, in yet another uprising in that part of the world. (This was called the Third Mithridatic War.) After a series of feints and withdrawals, Pompey's forces confronted those of Mithridates and, finally, after 20 years of Roman futility, scored a decisive victory. Pompey continued on eastward and claimed Syria, Judea, and Jerusalem for Rome. Back in Rome, Crassus was solidifying his hold on Roman power and entering into an alliance of necessity with Julius Caesar, who by then had secured his position as one of the most promising military and legal minds in Rome. With Pompey returned again the conquering hero to Rome in 61, trouble was brewing again. Caesar, however, convinced Crassus and Pompey in 60 to join him in a new form of a government, a three-man structure that was termed the First Triumvirate. In effect, they were the three most powerful men in Rome and took steps to ensure that they did the ruling. To cement the alliance, Caesar approved of Pompey's marrying Caesar's daughter, Julia. The arrangement worked to the benefit of all three, inside the halls of the Roman government and elsewhere in the Republic. They divided Rome's provinces between them, with Pompey taking Spain, Crassus ruling Syria, and Caesar presiding over Gaul and Illyrica.

Not only a soldier, Pompey liked theater as well and poured money into what became the Republic's first purpose-built permanent theater. The large building complex had shops, gardens, and a temple. Pompey's wife, Julia (Caesar's daughter), died in childbirth in 54. Caesar, who by that time had invaded Britain not once but twice, offered his grandniece Octavia (sister of Octavian), but Pompey refused. Crassus was killed on a military mission in 53. With Caesar away in Gaul, Pompey was declared sole consul. The following year, he refused to sanction Caesar's election to the consulship because (being still in Gaul) he wasn't in Rome. This was the latest in a growing number of differences between the two men that eventually resulted in military conflict. In 49, Caesar had finished off Gaul and was, with his men, marching back to Rome. Ordered by the Senate not to enter Rome proper with his legions, Caesar refused. When they crossed the Rubicon River, the Senate declared him in revolt and enlisted Pompey to defend Rome. Caesar allowed Pompey to retreat wherever he wanted, and Pompey chose Egypt. The young Ptolemy XIII had ideas other than letting Pompey grow old in Egypt and ordered the general's assassination. Pompey was stabbed just as he reached Egypt and died on the beach. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

A string of victories followed. Pompey ended the revolt of Sertorius in Spain, although it took him five years to do it, and returned to Rome a popular conqueror. In 70 B.C., he was named consul, along with

A string of victories followed. Pompey ended the revolt of Sertorius in Spain, although it took him five years to do it, and returned to Rome a popular conqueror. In 70 B.C., he was named consul, along with  The division pacified the jealousy between the three powerful men for awhile, but the alliance began to disintegrate in 56. Caesar called both Crassus and Pompey to a secret meeting, the Lucca Conference, at which the three men hammered out a way forward. The following year, Crassus and Pompey were again elected consuls and Caesar set out for Gaul.

The division pacified the jealousy between the three powerful men for awhile, but the alliance began to disintegrate in 56. Caesar called both Crassus and Pompey to a secret meeting, the Lucca Conference, at which the three men hammered out a way forward. The following year, Crassus and Pompey were again elected consuls and Caesar set out for Gaul.