The Roman Republic

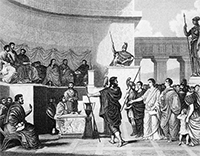

Part 1: The Early Years The Roman Republic began, Roman tradition holds, in 509 B.C., with the overthrow of the last of the Seven Ancient Kings of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, or Tarquin the Proud. The Romans had had enough of kings and declared a republic (res publica, or "thing of the people") whose two top officers were consuls. The Comitia Centuriata, or the Centuriate Assembly, elected the consuls to one-year terms. Each consul was essentially a king in terms of the power he held, presiding over the Senate and serving as judges and commanding the armies; but one consul could veto the actions of the other consul, and so that was a kind of check on power that the Senate did not have with the kings. A consul was head of the Centuriate Assembly. The powers of this assembly also included electing censors and praetors, ratifying census figures, and declaring war. A censor had power in three important areas: keeping the census (record of population makeup), supervising the public morality, and providing oversight in key areas of public expenditures. A praetor was an army commander of elected magistrates who had had specific duties, most notably the administration of justice; the praetor was commonly the chief judge.

The other consul was head of the Comitia Tributa, or Assembly of the Tribes. The word "tribe" in this case meant members of one of Rome's 35 geographical subdivisions. This assembly had the power to elect aediles, quaestors, and military tribunes. An aedile was in charge of maintaining public buildings and keeping order at festivals and other public events. A quaestor had great financial oversight, of government and military budgets. Protecting the Roman people from governmental oppression were the tribunes. Romans had the right of provocatio, an early form of due process that was, in essence, protection from coercion, by which they could appeal a magistrate's decision to a tribune.

By this time, Roman people (who weren't slaves) could be divided into two classes: patricians and plebeians. The former were wealthy, landowning citizens (members of a few dozen families known as gentes) who had money and power and wealth and the right to vote. The latter were none of the above (or very little) but were not slaves. Since the patricians made up most of the ruling class and made the laws, they tended to make laws to protect their own interests. If the interests of the plebeians got in the way, then the laws came first–at least that's what the patricians thought. Plebeians far outnumbered patricians in terms of sheer numbers; in raw power, however, patricians were superior. The plebeians had other ideas. They wanted certain basic rights, and they were willing to cause civil disturbances to get them. They even threatened to secede, in 494. In a great act of civil disobedience known as the Conflict of Orders, a number of plebeians gathered outside Rome and refused to move until the patricians gave them political representation. By this time, the sheer numbers of the plebeian class made the patricians sit up in their governing chairs and take notice. One immediate result was the Concilium Plebis, or Council of the Plebs; overseeing this were tribunes, elected by the council. Another result, 40 years later, was the Twelve Tables. In 287 B.C., the Council of the Plebs got even more power through the Lex Hortensia, which stipulated that all laws passed by the Council of the Plebs applied to both patricians and plebeians. Next page > The Senate > Page 1, 2, 3, 4 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White