The Montagnards of France

The Montagnards were, for the most part, radical political activists during the French Revolution.

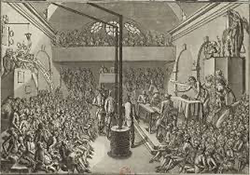

The Montagnards took their name from their habit of sitting in the top benches in the National Convention, the country's legislative body from 1792 to 1795. Among the leaders of the Montagnards were Maximilien Robespierre, Georges Danton, Camille Desmoulins, Jacques Hébert, Bertrand Barére, and Jean-Paul Marat. Their main political opponents were the Girondins. The Girondins, so named because they were generally from the Gironde, formed a tight-knit faction for the duration of their existence. The Montagnards were united in their opposition to the Girondins but not of similar minds with regard to much else in the way of public policy. Marat, in particular, was fond of hurling insults at Girondins, most commonly in form of his newspaper, L'ami du Peuple (The Friend of the People). The Girondins and Montagnards both were members of the Jacobin Club, the most well-known of France's political clubs. The Girondins, because of their unity, achieved much more of a solid voice and presence in government than did the Montagnards. The Girondins dominated both the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention, but it it was in the latter that they began to lose their influence. The war that so many Girondins and others had wanted to bring about began in early 1792. It did not go well. France lost a series of early battles against Austria and Prussia, and things looked bleak for much of the year. The Duke of Brunswick issued the Brunswick Manifesto, which proclaimed that any harm inflicted on the French royal family would result in devastation of Paris. He then marched at the head of an allied force of Austrians, French émigrés, Hessians, and Prussians, into the heart of France, besieging Verdun and then marching on Paris. What looked like certain French defeat turned into something entirely different at Valmy, on Sept. 20, 1792. French artillery ruled the day, and the allied force retreated.

Meanwhile, the landscape inside France had changed rapidly. In August, as French troops were regrouping, a crowd of radicals stormed the Tuileries Palace and seized the royal family, placing them in lockdown in the Square du Temple. The next month, on the same day that French guns had won a resounding victory at Valmy, the Legislative Assembly had transferred its lawmaking authority to the National Convention. Within two days, the Convention had abolished the monarchy and declared the French Republic. Also significant in September 1792 was a series of massacres of political prisoners who had opposed the Revolution. Girondins denounced such violence and blamed the Montagnards for endorsing it. From this point, the Girondins were the more conservative of the group of republicans, as the Montagnards and others advanced more and more radical ideas. Although many Girondins eventually voted to execute King Louis XVI, it was the Montagnards who had been most vocal in calling for such an outcome. The Montagnards began to gain the upper hand in 1793. The guillotine had claimed the king in January. France had fared badly on the battlefield again. In April, Marat was arrest and appeared before the Revolutionary Tribunal. He delivered a passionate defense and won acquittal, giving him even more prestige and influence and weakening the Girondins' hold on power further.

The downfall of the Girondins came on May 31–June 2, 1793. A popular uprising by the Paris Commune and a large number of sans-culottes joined with a move of ouster by the Montagnards within the Convention, and the result was a purge of Girondins as Convention deputies and the arrest of dozens of them. The Montagnard takeover of the government was complete. The Montagnards wasted no time dismissing a draft constitution put forward by the Girondins. Heading up a committee to write the constitution was Louis Saint-Just, one of the powers behind the Committee of Public Safety. The committee produced a draft in eight days. The final version, decreed on June 24, advanced further the cause of political democracy adding to the pronouncements of the Declaration of the Rights of the Man and of the Citizen such principles as the specific application of all laws to all people equally and the institution of universal manhood suffrage without any requirement of property ownership, pertaining to both voting and holding office.

A popular vote of July 1793 ratified the Constitution of 1793, and the Convention officially adopted it on August 10. Accompanying the new Constitution was a new Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. For all of its expansion of rights and guarantees and protections, the Constitution of 1793 was in effect for just a few months. Enacted in the middle of the War of the First Coalition as it was, it gave way to a revolutionary government, proclaimed in October, which took the form of the Reign of Terror. Directing the Reign of Terror were Robespierre, Saint-Just and other Montagnards. They eliminated thousands of alleged enemies of the state, eventually turning on their fellow Montagnards Danton and Hébert.

The Montagnards lost one of their own on July 13, 1793, when the Girondin sympathizer Charlotte Corday murdered Marat as he lay in his bath. That was during the early stages of the Reign of Terror, however, and the Committee of Public Safety and the Revolutionary Tribunal carried on in their campaign to eliminate their rivals. During the nearly 18 months of the Reign of Terror, more than 17,000 people met their deaths at the hands of the guillotine.

The end of the Reign of Terror is generally regarded as the death of Robespierre, himself a victim of the guillotine on July 28, 1794. The arrest of him and his followers was part of an overall series of events known as the Thermidorian Reaction (after the month of the year as listed in the newly created Republican Calendar). Any and all surviving Montagnards were rounded up, much as had been done by the Girondins, and executed or sent out of the country. By 1795, the Montagnards were no more.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White