The Reign of Terror

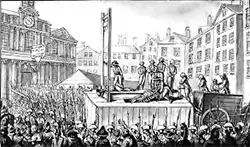

The Reign of Terror was a period of civil unrest in 18th-Century France during which thousands of people died at the hands of the government.

Historians differ on when the Reign of Terror began. Some scholars point to the execution of King Louis XVI, which took place on Jan. 21, 1793. Others prefer a more literal beginning, such as the Sept. 5, 1793 speech by Bertrand Barére to the National Convention, in which he said, "Let's make terror the order of the day." Sources generally agree on when the Reign of Terror ended: July 28, 1794, with the death of Maximilien Robespierre. The lawyer-turned-politician-made-dictator is the mostly widely known figure to have held power in France during this time period. A onetime advocate of equality for all, especially the poor, Robespierre presided over the executions of thousands of rich and poor perceived enemies of the state. In one of many speeches that he made in front of the National Convention, he said, "Terror is nothing more than speedy, severe and inflexible justice."

The French Revolution was well and truly under way by this time. After the Storming of the Bastille, the abolition of the monarchy, and the killing of the king, those who wanted a more republican government were very much in charge. France was at war with its neighbors, notably Austria and Prussia at this time, and it was going badly for France in early 1793. The government had ordered a large-sized conscription, or draft. A considerable number of men in the Vendé region of the country refused to report, others joined in, and the dispute became violent. To deal with internal enemies, the convention in March 1793 set up the Revolutionary Tribunal, a judicial body tasked with examining people charged with insurrection. By this time as well, the national legislature, the National Convention, had delegated much of its authority to a number of committees, the most prominent of which was the Committee of Public Safety, which the Convention created on April 6. During its first few weeks, the Committee was a model of revolutionary intent and action, focusing on shoring up the war effort and ensuring that no internal uprisings derailed the country's new path toward egalitarianism. Also during this time, the members of the Committee crossed the political spectrum, involving a mix of moderates and radicals, all of whom had to work together in order to effect the kind of change that they all wanted to see. Leading the way at this time was Georges Danton.

In time, however, as the country's war fortunes worsened, radicals gained control of the Committee and, still in secret, put themselves more and more in charge of more and more elements of society. Robespierre (right) won election to the Committee on July 27, 1793, and maintained his seat until his death. The same was true of other radicals such as Louis Saint-Just and Lazare Carnot. To Bertrand Barére the Committee left the writing of new laws and the reporting (more selectively as time went on) to the National Convention. Robespierre had demonstrated his power to mobilize public opinion by organizing a June 2 "visitation" of the Convention by hundreds of sans-culottes, to reinforce the idea that the Girondists (whose political enemies were the Montagnards) should be ousted from the Convention.

As more and more radicals controlled actions in the Convention, the Convention itself gave more and more power to the Committee of Public Safety. On Sept. 14, 1793, nine days after Barére had declared the terror was "the order of the day," the Convention handed over to the Committee the power to appoint deputies to other committees. On September 17, the Convention created the Law of Suspects, which greatly expanded the way in which people could be declared targets for arrest and punishment; following that was the Law of the Maximum, which set price ceilings in order to crack down on people engaged in price gouging. These measures concentrated in the Committee more and more power. This expansion of power resulted in more and more executions of so-called enemies of the state, notable among them Queen Marie Antoinette and the Girondin leader Jacques Brissot. On October 10, the Committee declared itself in charge of all of the government except the National Convention, to which the committee still nominally reported once a week. By this time, the leaders of the Committee were Robespierre, Saint-Just, and George Couthon. In reality, they were running the country and directing the Reign of Terror. The Committee's takeover of the government was complete on Dec. 4, 1793, when the Convention passed the Law of 14 Frimaire, or the Law of Revolutionary Government. Also known as the "Constitution of the Terror," this law gave to the Committee supreme executive power.

One of the main aims of the Reign of Terror was to eliminate enemies of the state. With the December takeover, the Committee had the power to decide who were enemies of the state. Even though Jacques Hébert and his followers had supported the Reign of Terror and, in particular, the Law of Suspects, the Committee declared them outlaws, as it were, and sent Hébert and the other leaders of his movement to the guillotine, in March 1794. This followed a pattern of the Committee's identifying former allies as enemies and then dispatching them. Another group targeted and dispatched were the followers of Georges Danton. The famous revolutionary himself was one of those convicted by the Tribunal and executed, in April 1794. In June 1794, the Committee created the Law of 22 Prairial, which put a structure around the process of identifying and punishing enemies of the state. Prisoners were denied lawyers, and witness testimony all but disappeared. Monumentally under this law, the punishment for all crimes delineated was death. This dramatically increased the number of state-directed deaths. In effect, it was nearly a straight line from arrest to execution. In the 13 months before the passage of this law, the Revolutionary Tribunal had delivered 1,220 death verdicts. In the first 49 days after the passage of this law, the number of executions was 1,376.  As the summer of 1794 continued, dissent grew inside the Committee. Robespierre and Saint-Just found themselves increasingly isolated, even though they retained enormous power. Recent military victories had convinced many that the Committee no longer had the country's best interests at heart and was overstepping the bounds of its original purpose, that of defending the country from foreign enemies. Robespierre gave a speech to the National Convention on July 26, 1794, calling for purges within the government's various committees. The next day, Saint-Just rose to speak at the Convention but didn't finish. He found himself at the center of a series of accusations with which he would have been all too familiar. Also targeted was Robespierre. The pair were arrested, along with a handful of their supporters, but not until they had taken refuge in the Hôtel de Ville and started planning an armed rebellion. Their attempt at insurrection failed. The leaders of the Terror were themselves sent to the guillotine, on July 28, 1794.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White