The Jacobins of France

The Jacobins were members of a number of political clubs in late 18th-Century France who played various roles in the advancement of the Revolution. France had several such clubs at this time in its history; the Jacobins were the most well-known and had the highest membership.

The club began in May 1789 as the Club Breton. The members of the club were representatives from Breton who had gone to Versailles as deputies in the Estates-General. The club began meeting at the monastery in Paris in October 1789 and took the name Society of the Friends of the Constitution. The word Jacobin was associated in early medieval times with the Dominican Friars, whose first monastery was in Rue Saint-Jacques (Saint James). The Jacobins, as they came to be known later, first met at a Dominican monastery called the Couvent des Jacobins in the Rue Saint-Honoré.

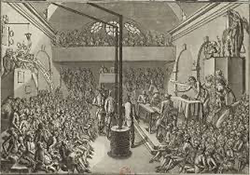

Membership grew as the club allowed deputies from other parts of France to take part in club discussions. In 1790, the club opened its doors to all non-deputies, even people from other countries. As the club's original name suggested, the members of the club pursued an agenda that was in favor of what would become the Constitution of 1791. They embraced the principles set out in the Déclaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. Many club members had voted for it while members of the National Constituent Assembly. In general, the Jacobins supported universal suffrage, the separation of church and state, universal access to education, and a system of government that protected all of these rights and more. The Jacobin Club motto was "Live free or die." This agenda appealed to a large number of people across France, and Jacobin Clubs sprang up around the country. (At their height, the organization is thought to have had 7,000 chapters and up to half a million members.) Members of Jacobin Clubs tended to be more well-to-do members of society, and they were always men: Women were not allowed. King Louis XVI tried to escape the country in July 1791. He was not successful and was brought back to Paris under armed guard. The Jacobins had been firmly of the position that the king should be the head of the government, but his attempted flight created a split in the Jacobin Club in the form of a subsequent debate over a petition that called for the king's abdication. Many Jacobins left the club in order to join a rival club, the Feuillants. Of those who remained in the Jacobin Club, the most prominent was Maximilien Robespierre. A full year later, the French Revolution evolved into a true drive for egalitarianism as its leaders overthrew the monarchy and declared a republic. A National Convention took the place of the National Constituent Assembly as a lawmaking body, and the new leaders of the Revolution began to pursue a much more radical agenda. The members of the Jacobin Club changed its named to the Society of the Jacobins, Friends of Liberty and Equality.

The remaining Jacobins further split as the republic began to take hold, forming two groups known as the Girondins and the Montagnards, the latter taking their name from their habit of sitting in the top benches in the Convention. The former were more moderate in outlook and counseled caution in what was then a time of great uncertainty. The Montagnards, however, wanted to see Louis XVI and his queen, Marie Antoinette, executed for their crimes against the state. The Girondins, led by Jacques Brissot and Jean-Marie Roland, essentially ran the country through the initial states of the republic and through a series of devastating military defeats. The Montagnards–led by Robespierre, Georges Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and Jean-Paul Marat, eventually triumphed, and the king and queen were killed.

The Girondins, so named because they were generally from the Gironde, formed a tight-knit faction for the duration of their existence. The Montagnards were united in their opposition to the Girondins but not of similar minds with regard to much else in the way of public policy. Marat, in particular, was fond of hurling insults at Girondins, most commonly in form of his newspaper, L'ami du Peuple (The Friend of the People). Girondin sympathizer Charlotte Corday murdered Marat in his bath and was later executed for the crime. The Montagnards gained the upper hand for good on June 2, 1793, when a group of tens of thousands of armed soldiers stormed into the Convention and voiced their support for Robespierre and his cohort. Rising to the height of power in the power vacuum that the king's execution created was Robespierre, who led not only the Committee of Public Safety but also, effectively, the rest of the government. Robespierre himself fell victim to the Revolution in July 1794, followed by a vicious anti-Jacobin reaction in Paris and elsewhere in the country. The Jacobin Club closed its doors. After a brief reappearance, the Club closed for good on Nov. 11, 1794.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White