The Road to the Civil War

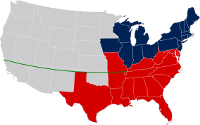

Compromise after Legal Compromise Missouri was only part of the Louisiana Territory, the giant mass of land that America had bought from France in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. That territory eventually yielded several other states, and the debate over whether those states would allow slavery dominated every discussion of entrance to the Union. With the Southern states' dependence more and more on slave labor to power the plantations and other economic engines of the Southern economy, Southerners more and more wanted to maintain some semblance of an equal representation in Congress with Northerners. Congress, mindful of this, strove to keep the balance between "slave states" and "free states." The U.S. victory in the Mexican-American War in 1848 brought into the Union a large amount of territory known as the Mexican Cession, which included all of what is now California, Nevada, and Utah and parts of what is now Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. The northern and western boundaries of Texas were also in dispute at this time. The discovery of gold in California in 1848 brought on the California Gold Rush, and California sought statehood. People in what would become the New Mexico Territory and the Utah Territory wanted to become part of the U.S. as well.

Geographically, these new lands were, for the most part, on both sides of the Missouri Compromise dividing line, and so Congress was struggling with whether to allow slavery in these new territories, which would probably become new states. The admission of Texas as a state in 1845 gave the South and the North an equal number of states. Anti-slavery sentiment was very strong in California, and many people thought that if California were admitted to the Union, it would be as a "free state." Southerners wanted to keep the balance and so were concerned about this possibility. California had outlawed slavery in its proposed state constitution, as part of its admittance to the Union, and it appeared that residents of the New Mexico Territory wanted to do the same. Negotiations between North and South continued for many weeks.

At the same time, another issue angering Southerners was that Northerners were not enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act, a Congressional statute passed in 1793 that guaranteed slaveowners the right to recover an escaped slave and also required anyone else living in North or South to help in that slave recovery. The Act had left enforcement in the hands of state governments, and many in the North turned a blind eye to the responsibility of helping slaveowners reclaim what they considered their "property." Indeed, some Northern states passed personal liberty laws that gave runaway slaves some form of legal protection. One exception to all of this was the District of Columbia, which resembled a state but didn't have the same sort of structure. The District of Columbia was nominally a federal territory, not a state, and so different laws applied to D.C. For one thing, the slave trade was legal in D.C. Northerners certainly wanted this because D.C. was the nation's capital. Southerners certainly did not want this, for the same reason. In 1846, at the advent of the Mexican-American War, Congress had considered adding to a bill providing funding for the war an amendment that became known as the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in any territories acquired from Mexico. The Wilmot Proviso was not approved and never became law, but discussion of it angered Southerners in Congress. Another avenue of discussion for the settlement of new American territories was Popular Sovereignty, the idea that people in a territory could decide for themselves, in their state constitution, whether they would allow slavery. This giving the people of a territory/state ran counter to the Missouri Compromise, under which Congress had established for itself the power to decide whether new states could allow slavery. Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois was a particular proponent of Popular Sovereignty.

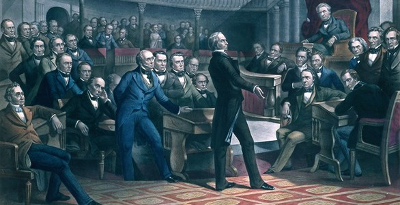

Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky was known as an astute politician who could get other people to listen to each other and even agree on certain things. He had brokered the Missouri Compromise back in 1820. Later in life, he became known as "the Great Compromiser" for his ability to break Congressional deadlocks. Clay was the architect of what came to be called the Compromise of 1850. In January 1850, he presented to the Senate a series of resolutions that he thought would, in some way, appease both North and South. To satisfy Southern interests, Clay argued that the federal government should appropriate the part of New Mexico Territory claimed by Texas and give it to New Mexico, paying Texas for the land. Also to satisfy Southerners, Clay championed a more stringent Fugitive Slave Law, one that introduced punishments for people known to have broken the law and a federal patrol whose function was to enforce the law. (This, in effect, made the original statute, which devolved responsibility to the states, into a federal one, with the financial and military power of the national government behind it.) To satisfy Northern interests, Clay championed the admission of California as a "free state" and the abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia.

On the organization of what became the New Mexico Territory and the Utah Territory, Clay relied on Douglas's idea of Popular Sovereignty to allow the residents of those territories to decide for themselves whether they would allow slavery. In a sense, this proposal could have been said to appeal to both Northerners and Southerners. Congress in April created a committee of 13 to hash out the details of whatever bills were to be voted on; the result was a proposal of an omnibus bill by Clay to Congress on May 8. The bill as a whole found enough detractors (including the senior statesman of the South, John C. Calhoun) that it failed in the Senate, convincing Clay to return to the idea of five separate bills. The addition of the venerable Daniel Webster as a support of the bills gave them much-needed support. By this time, however, Clay was physically ill and had to leave the Senate. Douglas carried on and got the job done. Both the House of Representatives and the Senate passed all five bills between September 9 and September 20, and President Millard Fillmore, who had made known his preference to seek such a compromise, signed them into law. Next page > Abolition and Violence > Page 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Congress passed a series of compromise laws intended to stave off what many feared would be a violent resolution to the conflict over slavery. The first major such law was the

Congress passed a series of compromise laws intended to stave off what many feared would be a violent resolution to the conflict over slavery. The first major such law was the