The California Gold Rush

The discovery of gold in California in the mid-19th Century ushered in one of the largest migrations in American history, as tens of thousands of hopeful, excited, and just plain desperate participated in the California Gold Rush.

Despite this agreement, the story got out, possibly because Marshall wouldn't have been the only one to notice the gold in the millwater. Nevertheless, the story was soon a well-travelled one, with a publisher named Samuel Brannan soon walking up and down the streets of San Francisco holding a jar full of gold. The first major East Coast newspaper to report Marshall's discovery, the New York Herald, did so on August 19. President James K. Polk told the nation about the gold discovery in an address to Congress on December 5. Before long, the rush was on and '49ers, as they were called (after the year in which they set out, 1849), descended on California by the tens of thousands. In 1849, the gold-motivated migrants numbered 80,000. Most of those were Americans in 1849, but the following few years saw gold-seekers come from all over the world. By 1856, more than 300,000 people had followed their gold dreams to what they hoped were the gold fields of California.

Many of the '49ers and other prospectors who came to California in search of a dream found they liked the place enough to stay. San Francisco went from an 1846 population of 200 to an 1852 population of 36,000. Other California cities and towns experienced similar growth. As a result, California became a state, in 1850, its infrastructure growing by leaps and bounds: Schools, churches, roads, and businesses rose from empty land, as many people found themselves earning a good living by providing goods and services to prospectors. Supply stores, warehouses, taverns, and hotels dotted the landscape, surrounding the areas where gold was known to be. Modern-day estimates from the U.S. Government put the amount of gold discovered in the first five years of the California Gold Rush at 12 million ounces, worth more than $16 billion in today's dollars. Many settlers made homes for themselves by displacing (and, in some cases, ending the lives of) Native Americans, continuing a Manifest Destiny trend that had begun in the East and continued in the Midwest and South.

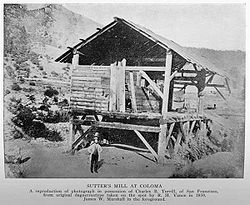

The legality of various prospectors' claims to gold was not at all straightforward. When Marshall first found gold, on January 24, the land was still technically owned by Mexico, although that country had surrendered to U.S. forces, ending the Mexican-American War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which officially ended the war, went into effect on February 2. Even then, California was under the control of the U.S. Military. American soldiers did not roam the gold fields, however. The areas were largely self-policed, which allowed for all sorts of varied rules of law. As towns sprang up, rural law enforcement made its presence felt. What this meant for the initial waves of prospectors, however, is that the gold was theirs for the taking, no questions asked, no taxes assessed, no price to be paid other than the hard labor expended to find the gold in the first place. Protecting that find proved problematic for many. The only real solution to the lawlessness that existed in some areas was the drying up of the gold deposits, making it unpalatable for anyone looking for quick and easy wealth. The California Gold Rush was not kind to Sutter or Marshall, either. Unequipped with his own private security force, Sutter could do little to stem the tide of prospectors who camped on the land on which he had intended to complete his sawmill. He saw his dreams of an agriculture bonanza dry up in the dust left by prospectors' boots and horses' hooves. Marshall had little luck prospecting, either. Both men died poor and forgotten, except for the part that they played in setting off the Gold Rush in the first place. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

It all began on January 24, 1848, on the South Fork of the American River, near what is now the California town of Coloma.

It all began on January 24, 1848, on the South Fork of the American River, near what is now the California town of Coloma.  In the beginning, prospectors could find gold nuggets by sifting through the top one or two layers of dirt or in streams and riverbeds, using methods such as panning. As the gold supply dwindled and desire for gold increased, prospectors employed more sophisticated methods.

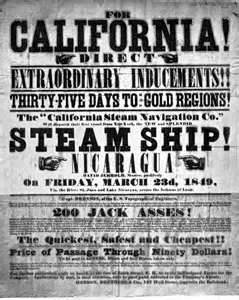

In the beginning, prospectors could find gold nuggets by sifting through the top one or two layers of dirt or in streams and riverbeds, using methods such as panning. As the gold supply dwindled and desire for gold increased, prospectors employed more sophisticated methods. Many others chasing their dreams found nothing but frustration. Many prospecting hopefuls spent all of the money that they had on the search for great wealth and ended up with none of their own. For many, the travel to California would have cost a steep price, especially if they had come from Latin America or Europe or China or Australia, as a great many did. The Americans who migrated westward generally crossed the Rocky Mountains or the Isthmus of Panama to get to gold country. People who came from other countries made great use of boats that docked in San Francisco and other, more southern ports.

Many others chasing their dreams found nothing but frustration. Many prospecting hopefuls spent all of the money that they had on the search for great wealth and ended up with none of their own. For many, the travel to California would have cost a steep price, especially if they had come from Latin America or Europe or China or Australia, as a great many did. The Americans who migrated westward generally crossed the Rocky Mountains or the Isthmus of Panama to get to gold country. People who came from other countries made great use of boats that docked in San Francisco and other, more southern ports.