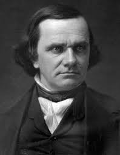

Stephen A. Douglas: Illinois' 'Little Giant'

Stephen A. Douglas was one of the most famous politicians of the early 19th Century. A Senator and presidential candidate, he is most well-known for his advocacy of the doctrine of Popular Sovereignty and for a series of debates that he had with Abraham Lincoln during a U.S. Senate campaign. Douglas was born on April 23, 1813, in Brandon, Vermont. His father died when young Stephen was 2 months old. The boy enjoyed a basic education.

He found work as a cabinetmaker's apprentice but found the work not to his liking. He much preferred the law. He traveled westward, living in Ohio for a time, and then settled in Winchester, Ill., where he found work as a teacher. He trained with a local lawyer and passed the bar in 1834, when he was 21. He set up his own law practice in Jacksonville. Douglas had been fascinated by the 1828 election of Andrew Jackson as President and was early interested in politics. In 1836, he ran for a seat in the Illinois House of Representatives and won. A strong, charismatic presence, he soon became a leader of his state's Democratic Party. The Illinois state government appointed Douglas secretary of state (the youngest person appointed to the office) and then an associate justice of the state supreme court in 1841; he resigned in 1844 to run for Congress. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives that year and then won election to the U.S. Senate in 1846. Once in the Senate, he made a name for himself on the Committee on the Territories, which was tasked with making momentous decisions on the boundaries and practices of new territories and new states. He favored the annexation of Texas and the necessity of war with Mexico. He worked with Henry Clay on the Compromise of 1850, a set of laws aimed at staving off a violent clash over the issue of slavery. Clay fell ill, and Douglas finished off the process. Douglas gained in prominence and national recognition, championing the idea of a transcontinental railroad and a national connection of waterways. One of his favored projects was getting rights-of-way for the Illinois Central Railroad, so a line could run from Chicago to Mobile, Ala. He was not tall but had a powerful, persuasive personality and manner, and he became known as the "Little Giant." He was in the running for the Democratic Party nomination for President for the Election of 1852. After a long and contentious series of ballots at the national convention, the party nominated Franklin Pierce, who won the election. Douglas won re-election to the Senate that year and became a prime proponent of the doctrine of Popular Sovereignty (a term he coined), the idea that the residents of a new territory or state could decide for themselves whether their territorial or state laws would allow residents to own slaves. The U.S. had recently won a war against Mexico and, with it, a large amount of new territory. Settlers were more and more populating these new lands, and calls for territorial status were growing. Douglas achieved his goal of embedding Popular Sovereignty into American law with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, an 1854 statue that laid out the terms of statehood for the Kansas Territory and the Nebraska Territory. The idea that the residents of a territory or state could decide for themselves on the question of slavery was in contravention of an earlier established law, the Missouri Compromise, under which Congress had retained the right to stipulate the slavery status of new states. Douglas himself supported the abolition of slavery (and was one of only four Democrats to oppose the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in any part of the Mexican Cession), but he also believed in Popular Sovereignty. The Democratic Party refused to support a re-election bid by Pierce in 1856, and Douglas was again a frontrunner for the party nomination. Again he was passed over, this time in favor of James Buchanan, who also went on to win election. The Dred Scott decision in 1857 challenged the efficacy of Popular Sovereignty and put Douglas in a bind as to whether to come out in support of the decision or whether to oppose it. He decided to walk the tightrope between the two, announcing the Freeport Doctrine, which said that territories should be able to refuse the spread of slavery despite the Dred Scott decision. Douglas ran for re-election to the Senate in 1858. Opposing him was Abraham Lincoln, a relatively inexperienced Congressman. The two candidates engaged in a series of spirited debates, traveling around the country. Lincoln gained a large amount of recognition from these debates. Douglas, however, won the election. In the presidential election of 1860, Douglas finally won the Democratic Party nomination. His timing could not have been worse. The national government's long series of compromises had not stemmed the tide of division, and the Democratic Party had split along geographical lines. Douglas was the candidate of the Northern Democratic Party; John C. Breckinridge was the candidate of the Southern Democratic Party. The presidential candidate of the relatively new Republican Party was Douglas's Illinois Senate opponent, Lincoln. Taking advantage of the split in the Democratic Party, Lincoln forged enough of a coalition in the Northern states to win a majority of electoral votes and the presidency. Douglas won the second-highest total of popular votes, but his support was also in the north and so he finished first overall in only one state, Missouri. After the election, Douglas publicly expressed his support for Lincoln. Douglas married twice, to Martha Martin in 1847, and to Adele Cutts in 1856. Stephen and Martha had two sons; Martha died during the birth of their third child, who died not long afterward. Stephen and Adele had a daughter, who survived just a few weeks. Douglas contracted typhoid fever died and died, on June 3, 1861. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White