The Abolition of Slavery in America

Slavery began with the arrival of the Dutch trader ship White Lion to the Virginia colony in 1619. All of America's original 13 Colonies, with the exception of Georgia, allowed slavery initially.

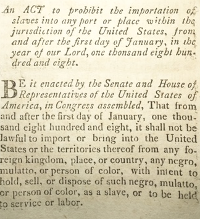

Members of the Mennonite faith and the Society of Friends (Quakers) were early proponents of the abolition of slavery in America. Pennsylvania, in 1688, adopted the first formal resolution against slavery. The colony followed suit nearly a century later with the formation of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery and had much earlier passed laws restricting the slave trade. Other Northern states eventually followed suit. The first official abolition group in what is now the U.S. was the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, formed in April 1775 in Philadelphia. In that same year, independence activist Thomas Paine wrote an essay titled "African Slavery in America," in which he advocated the abolition of slavery. The advent of the Revolutionary War soon afterward led to a suspension of this group's activity. The group took up where it left off after the war, in 1784, with Benjamin Franklin as president. Another group instrumental in the early days of the abolition movement was the New York Manumission Society, founded by John Jay and populated by such luminaries as Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. Vermont in 1777 was the first state to abolish slavery. Most states north of the Mason-Dixon Line followed suit. Emancipation occurred gradually. The Northwest Ordinance in 1787 created the Northwest Territory and outlawed slavery in the territory and, by extension, any state created from it. That eventually included Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Slavery was a topic of discussion at the Constitutional Convention. Some of the discussion at that convention involved language in the Constitution that came to be known as the Fugitive Slave Clause. Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 states: "No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, But shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due." Also at the Constitutional Convention, Congress agreed to abolish the international slave trade but not for awhile yet. As for the internal slave trade, Congress took no action or gave any hint that it would anytime soon. President Thomas Jefferson in 1806 called for an end to the international slave trade, and Congress passed a law to that effect the very next year. That law, the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, went into being on Jan. 1, 1808. The United Slaveowners in Delaware and Maryland gradually emancipated their slaves, as did a significant number in Virginia. Such practices were rare in the Deep South, where much of the economy was driven by slave labor. One of Congress's many attempts to keep the peace regarding slavery was the Missouri Compromise in 1820. During Congressional debate on the admission of Missouri as a state, Sen. Rufus King championed a proposal to ban slavery in the new state, in an addition to the bill that became known as the Tallmadge Amendment because Rep. James Tallmadge, Jr., of New York was the one who introduced the rider into congressional debate. Congress voted down the amendment, and Missouri entered the Union as a "slave state." Also as part of the Missouri Compromise, Maine entered the Union as a "free state," prohibiting slavery. By this time, Alabama and Mississippi had also entered the Union, as states allowing slavery, and Illinois and Maine had entered as free states. The statehoods of Arkansas (1836), Florida (1845), and Texas (1845) were the exceptions to what was otherwise a free state trend, with the Northwest Territory states joining and then California (1850), Minnesota (1858), and Oregon (1859). Joining the Quakers in the religious groups' objections to the practice of slavery on moral grounds were the Methodist and other churches, in the wake of the Second Great Awakening in the 1820s and 1830s. By contrast, many churches, especially in the South, used religious arguments to justify the maintenance of slavery.

A number of abolitionist groups began in the early 19th Century. One of the most famous was the American Anti-Slavery Society, founded by William Lloyd Garrison (left), a newspaper publisher. His abolitionist paper The Liberator was a major force in the abolitionist movement for many years. Minister Theodore Weld and free African-American Robert Purvis were instrumental in the founding of Garrison's organization. One of the famous members was former slave Frederick Douglass. Joining in the abolitionist movement were many prominent women, including Angela Grimké, Sarah Grimké, and Lucretia Mott, later one of the leaders of the women's suffrage movement. Later joining Mott in the drive for abolition were fellow suffrage movement leaders Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone. Other famous female abolitionists included Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, the famed Underground Railroad "conductor."

One of the most influential publications in the history of the abolition movement was Uncle Tom's Cabin, a novel by Harriet Beecher Stowe that described in often horrendous scenarios the life that African-American slaves endured in the South. The book first appeared in 1852 and was very widely read across the country. Stowe later said that she wrote the book in part as a reaction to the strengthened Fugitive Slave Law that was part of the Compromise of 1850. (That set of laws also outlawed the slave trade in the District of Columbia.) One of the most famous acts of insurrection in the abolition movement was the seizing of the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry by John Brown. This 1859 series of events, which ended with Brown's capture and eventual execution, also helped galvanize sentiment against the horrors of slavery.Brown was a prominent abolitionist who advocated a violent end to slavery. He wanted to take the weapons from the Harpers Ferry arsenal and distribute them to slaves, in order to facilitate an armed uprising. Other abolitionists favored violence, if needed, to end slavery, arguing that the end would justify the means. One of the more prominent of these was Henry Ward Beecher, brother to Harriet Beecher Stowe. Beecher sent guns to aid the anti-slavery effort in Kansas, saying that one gun was worth a hundred Bibles. The guns came to be known as "Beecher's Bibles." The Kansas-Nebraska Act created the Kansas Territory and the Nebraska Territory and left the question of whether to allow slavery up to the territories' residents. Kansas became a state in 1861 and had a state constitution that banned slavery. Nebraska became a state after the Civil War, and so slavery was prohibited by law.

The Republican Party, formed in 1854 in the wake of the dissolution of the Free Soil Party, the Know-Nothing Party, and the Whig Party, had the abolition of slavery as one of its cornerstone policies. That party's second presidential candidate, Abraham Lincoln, won the presidency in 1860. Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, freeing slaves held in the Southern states, and this convinced border states like Delaware and Maryland to begin their own emancipation efforts. In the end, it took a war and an amendment to the Constitution to abolish slavery in America. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

Kingdom had passed a similar law in 1807. The importation of foreign slaves into America was against the law; the trading of slaves within the United States was still protected.

Kingdom had passed a similar law in 1807. The importation of foreign slaves into America was against the law; the trading of slaves within the United States was still protected.