Slave Plantations in America

One of the most recognizable symbols of the slavery system in the United States was the slave plantation, a collection of fields and other land, buildings, and people. The plantation was primarily an agricultural instrument, and the most common crops grown on plantations in the U.S. were cotton, rice, indigo, sugar cane, and tobacco.

Tobacco was the crop of choice in the early colonies and remained so in the Upper South. In the Deep South, far and way the most prevalent crop grown and harvested on plantations was cotton. It brought a high price, especially in British markets, and it had many uses. Picking cotton was backbreaking work. Plantation owners sometimes employed indentured servants to pick cotton, but the majority of the people who did such physically demanding work were slaves. The invention of the Cotton Gin made it much easier and quicker to produce clean cotton. The brainchild of inventor Eli Whitney, the cotton gin could enable one slave to produce up to 1,000 pounds of cotton a day. Before 1792, when Whitney unveiled his invention, it would take a slave 10 hours to produce 1 pound of cotton. The potential to produce that cotton encouraged cotton plantation owners to plant more cotton, creating more demand for picking and, in many cases, demand for more slaves to do that picking. "King Cotton," as it was termed, dominated the Southern economic scene for decades. By 1850, annual exports to textile mills in England topped 1 million tons. As a result, 4 million slaves were needed. A large number of slaves who lived on plantations worked the fields, picking cotton or other crops and otherwise tending to the fields and everything that went along with growing a crop: digging ditches, ploughing, sowing crops, cutting and hauling wood, repairing tools and machines. Indeed, some slaves were or became quite skilled in blacksmithing, carpentry, and mechanics. Outdoor slaves who did not work in the fields tended fruit and vegetable gardens. Other plantation slaves tended to more domestic tasks, such as cooking, sewing, spinning, and weaving. Many female slaves looked after the children of plantation owners. The owners of plantations lived in stately, sometimes luxurious quarters, usually a large house or collection of houses. Tending to the needs of the owner and family were household slaves.

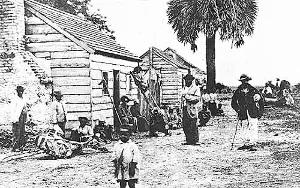

Slaves, by and large, lived in slave quarters, which were separate buildings, usually poorly constructed wooden huts, that had very little of the trappings of the plantation mansion. Living spaces were crude and crowded, with sanitation at a minimum. Illness was almost never a cause for being excused from work. This combination of factors, along with inadequate nutrition, led to many slave deaths. Particularly deadly to slaves were conditions on rice plantations. Forced workers in such places had to stand in water for hours at a time, in at times unbearable heat. Malaria was an effective killer on rice plantations, especially of young slaves. Conditions were harsh on other plantations as well. Forcing slaves to work were masters and overseers, who imposed harsh discipline, at times for the slightest offense. Beatings were commonplace, as was imprisonment. Punishment also took other forms: slaves wore shackles, manacles, or masks. Plantation deaths of slaves, for whatever reason, were all too common. Overseers tended to live in their own quarters, separate from both plantation owner and slaves. Supporting all of this enforced servitude were a set of state and federal slave laws, passed at various times throughout the history of the colonies and country. These laws were also called Slave Codes and served to reinforce the belief that many white people had that African-Americans were inferior and could be treated as property (and, as such, be owned). The punishment meted out on a slave who escaped but was caught was usually unbelievably harsh, in order to serve as an example for anyone else who was thinking to try to escape. Many slaves did escape, however, particularly along the Underground Railroad. Slaves did rebel, sometimes violently so. Well-known large-scale slave rebellions were few. Much more common were low-scale acts of disobedience, such as feigning ignorance or illness or sabotaging crops, machines, or tools. A list of plantation owners who owned the most slaves includes these:

Many plantation buildings were torn down as the South began to industrialize in the same way that the North had. Some remain, as stark reminders of America's harsh past. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White