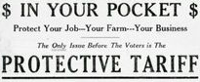

The American Government has relied on tariffs as a means of income since the earliest days of the country. The three usual motivations cited by various officials have been revenue, restriction, and retaliation. Simply put, a tariff is a tax that a government places on imports of goods into the country or on exports of goods out of the country. The former is far more common than the latter. A tariff can be fixed, so the same amount per unit or the same percentage of the overall price; a tariff can be variable, so a different amount according to price. Far and away the most common reason for a country's government to impose a tariff on imported goods is to encourage the citizens of that country to buy local goods, not goods made elsewhere. The more local goods that consumers buy, the more revenues stay in the country. A government might impose a tariff in order to protect domestic businesses (thus the term protective tariff).

The United States has a long and complex history of tariffs, dating to the first year of the country's existence as a constitutional republic. The Tariff of 1789 was the result of a bill approved by Congress and signed into law by the nation's first President, George Washington. In fact, that tariff was the country's second-ever law. (The first was the Oath Act, which required members of Congress and other federal employees to swear an oath that they would support the Constitution.) The Tariff of 1789 placed a tax of 50 cents a ton on imported goods that came to the U.S. on foreign ships; American-owned ships paied a much lower tax, 6 cents a ton. A parallel piece of legislation, the Collection Act of 1789, created the U.S. Customs Service, to collect the tax, and specified ports of entry at which that tax would be collected; another law the following year created an enforcement agency, the Revenue Cutter Service, which morphed later into the Coast Guard. The Tariff of 1789 was the first of many tariffs initiated by the U.S. Government; in fact, the tariff was the predominant method of revenue collection for the first 120 years of the country's existence. Americans didn't invent the tariff. Such measures were not uncommon in European powers. The American colonists from England would have been familiar with the idea of a tariff from their days living in England and Great Britain or certainly from their ancestors. Britain's first prime minister, Robert Walpole, was a fan of the tariff; his successors, more often than not, followed suit. A prominent American who was very much in favor of protectionist tariffs was Alexander Hamilton, a founder of the Federalist Party and the nation's first Secretary of the Treasury. One of his main motivations in promoting such a strategy was to protect the nascent industries that had gained footing in the years leading up to the Revolutionary War but had lost momentum during the war; postwar competition with the better-faring British industries would have been cost-prohibitive, and so Hamilton championed protective measures as a way of reducing that competition. (One other method of revenue was the excise tax, on domestic goods. The most famous of these was perhaps the one placed on whiskey, which sparked the Whiskey Rebellion. It took Washington at the head of an armed force to suppress that uprising; as it was, the tax didn't raise all that much and the country's third President, Thomas Jefferson made it disappear.) In the period between the advent of Walpole in Britain, in the first half of the 18th Century, and the creation of America's constitutional government, the American colonies operated somewhat independently in the levying of tariffs, although one common factor was that British products had lower tariffs than goods from other colonies. (The British Government insisted that only British ships supply goods to the American colonies.) Once the colonies were united, however, it was an all-for-one strategy of protectionism, to help the new country find its footing on the international stage. That thinking continued to dominate in the second war between the U.S. and Great Britain, which by that time had become the United Kingdom. U.S. tariffs dominated the revenue-raising methods of the young U.S. during the War of 1812. A national tariff two years after the end of that war, the Tariff of 1816, served the function of what would today be an income tax in that it generated revenue in order to offset a project budget deficit, brought on by the prosecution of the recent war. The tariff was a markup of 25 percent on manufactured goods, and, as written, had a shelf life of three years. By the end of that period, sectionalism had taken hold in Congress and in the country as a whole and no agreement on extending the tariff could be reached. The very next year, Congress implemented the Missouri Compromise as a way to keep the country together, not by expressing a common nationwide goal but by pacifying two massive competing interests. By that time, the divide between an agrarian and slave-holding South and a manufacturing-focused (and more abolionist) North had formed. Even the usually tariff-reticent Daniel Webster joined his fellow Whig Henry Clay in calling for higher tariffs as a means of raising money, most notably in the Tariff of 1824. The Whigs' American System had coincided with a great expansion in territory and advances in technology, but Southern interests had, by the 1820s, turned inward; by the time of the Tariff of 1824, Southerners were much more concerned with keeping their plantations and other elements of Southern society running than they were with paying for roads and turnpikes that they might not use all that much. The same was true of tariffs, since the usual beneficiaries, manufacturing, were predominantly in the North. The evenual tariff did include measures of protection for wool and cotton textile markets in the form of a 35-percent markup, but it was still by and large a strategy that favored North more than South. Four years later, the difference in focus was even starker. The Tariff of 1828 was deeply unpopular in parts of New England and the South and was so detrimental to South Carolina, in particular, that that state began to agitate for a political response. South Carolina's own John C. Calhoun was Vice-president at the time, having been elected with Andrew Jackson in 1828. The common epithet given to this unpopular tax was the "Tariff of Abominations." Because of a post-War of 1812 economic downturn, several states, including South Carolina, were suffering. The new nation had suffered its first financial crisis, called the Panic of 1819; and South Carolina had not really recovered. Calhoun had supported, then opposed the earlier tariffs. His opposition had strong ties to his own personal belief (and one that was growing across the country) that states should have stronger rights within the new constitutional republic. Virginia in 1826 passed a resolution in the state legislature, asserting that the tariffs were unconstitutional and using the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions as justification. Even though the 1828 tariff was an "abomination" in equal parts Northeast and South, depending on which state the poll would have been taking, it was the Southern states that were generally more seriously affected and one Southern state, South Carolina, that did something legislative about it.

Southerners had lined up in opposition to the Tariff of 1828 and had thought that the newly elected Jackson, from the South, would get to work dismantling the tariff. He did no such thing, even at great urging from Calhoun, his Vice-president. As the state economy continued to struggle, the mood in South Carolina continued to sour and many began to call for nullification. Calhoun felt so strongly about the issue that he resigned as Vice-president (one of only two ever to do so) in order to serve in the Senate, in which he thought he could more effectively take up the nullification cause. (He filled the seat of Robert Hayne, who had resigned in order to run for Governor.) Calhoun had earlier written and gotten circulated South Carolina Exposition and Protest, a tract laying out the justification for nullification. Thus began the Nullification Crisis. In the meantime, Jackson and Congress had come up with a weakened tariff that most of the other states who had termed the 1828 tariff an "abomination" were more in favor of. On July 14, 1832, President Jackson signed into law the Tariff of 1832. Most Northerners and half of Southerners in Congress voiced their approval. Calhoun and the South Carolina delegation did not. A November state convention passed a resolution declaring both the 1828 and 1832 tariffs unconstitutional and unenforceable within the state borders of South Carolina beginning on February 1, 1833. President Jackson responded on two fronts, advocating the use of military force to bring South Carolina into line while also convincing Congress to work on yet another tariff, one that South Carolina might finally approve. Congress passed both a Force Bill and the Compromise Tariff of 1833 (negotiated by the Great Compromiser himself, Henry Clay). South Carolina responded by repealing its nullification ordinance. Despite this intense internecine struggle, Congress did not abandon the tariff. The focus shifted away from protection to almost an entirely revenue generation approach, though. Tariffs were lower and, as Congress directed, got lower and lower as the 1830s progressed. With the ascendancy of the Whigs to the presidency as well in the form of William Henry Harrison in 1840, however, the tariff was back as a prime strategy. Harrison's death, just weeks into his presidency, brought John Tyler into the White House and into opposition with Whig tariffs. Wrangling between Congress and Tyler reached a fever pitch with more than one presidential veto, but the end result was the Tariff of 1842, which turned back the clock to the high rates that had precipitated the Nullification Crisis, although the focus this time was mainly on iron imports. Not for the first time but possibly with the most severe result, the advent of a new tariff resulted in a decline in international trade. That had certainly been the intent of most of the protectionist tariffs, which were imagined as a shell around still-getting-up-to-speed American industries. But by the 1840s, American industry was booming, in both the North and the South, and such protections weren't always as desirable. One industry especially affected by the iron tariff was the burgeoning railroad industry, for most elements of that industry required hammered bar iron and rolled bar iron in great quantities. The Whigs lost control of both Congress and the White House in 1844, as Democrat James K. Polk won the presidential election and vowed to work in partnership with his party's new congressional majority. One result was the 1846 Walker Tariff (named for Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker), which sharply cut the tariff on iron and reduced overall tariffs from 32 percent to 25 percent. A railroading boom followed. As the country teetered on the brink of sectional conflict through the 1850s, Congress again turned to the tariff, replacing the Walker Tariff with the Tariff of 1857, which slashed rates even further, in some cases as low as 15 percent. Congress and then-President James Buchanan had the backing of a large budget surplus in seeking such tariff reductions. An economic panic that same year created much market uncertainty, but the Tariff remained in effect until 1861. The Morrill Tariff, named for sponsor Rep. Justin Smith Morrill (R-Vt.), was the product of a new Congress, populated by the relatively new Republication Party, and adopted on March 2, 1861, just two days before the inauguration of the new President, Abraham Lincoln. Outgoing President Buchanan signed the tariff bill into law, and Lincoln and his new Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon Chase, set about overseeing its implementation. The Morrill Tariff was a precipitous increase across the board, designed to bring into government coffers a greater source of funds for what was increasingly looking like war. South Carolina, in December 1860, had seceded from the Union; following suit in January and February 1861 were Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas. Those seven states formed the Confederate States of America on Feb. 8, 1861. Even under that shadow, however, the rates stipulated by the Morrill Tariff were lower than the ones in the "Tariff of Abominations." Once the war began, Chase pushed through another tariff, in the summer of 1861, in order to generate funds for paying soldiers, producing weapons, etc. That would have only exacerbated the deteriorating relationship with the U.K. The Union blockade of Southern ports had drastically reduced the South's ability to export cotton primarily but also other goods, and a significant part of English and Scottish industry still depended on American cotton exports; as well, the new tariffs would have been a reversal of a downward duty trend and so might have come as a surprise to the U.K. government but certainly would not have been welcome. Delicate negotiations by Lincoln, Secretary of State William Seward, and others kept the U.K. and other powers from recognizing the Confederacy, and the Union blockade stunted Southern trade significantly. But in order to continue to pay for the war effort, the U.S. Government continued to implement the tariffs, even after the war ended. Also in the war's first year, the Government brought in an income tax. The Revenue Act of 1861 put a 3-percent tax on all annual income more than $800. (That's the early-21st-Century equivalent of more than $20,000.) A slight modification a year later brought the taxable amount down to $600, meaning that it applied to even more Americans. The Revenue Act of 1862 had a four-year lifespan, however, and ended in 1866, a year after the Civil War ended. Another series of federal income taxes lasted until 1872, but the focus turned more fully to tariffs as the country's main source of income.

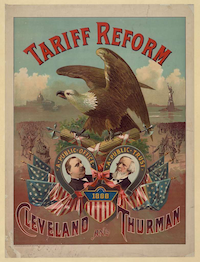

The advent of Reconstruction created a further need for tariffs, in the eyes of the majority-Republican Congress. Even so, tariffs remained the same sort of sectional issue that they had been before the war: Northern industrialists championed the tariffs, whereas Southerners and those who lived in the newly settled West wanted lower tariffs. Republican Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes presided over a preeminence of preference for tariffs in the 1870s, and the mood in the country was the same as the 1880s progressed. Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, won the presidency in 1884, lost it again four years later, then regained it four years further on. Through all of that, Cleveland, despite being governor of the highly industrialized state of New York, maintained his opposition to a national set of tariffs. Debates over such elements of economic policy formed a major part of the struggle for the White House in each election in which Cleveland ran. The 1888 election of Benjamin Harrison brought with it a new favor for tariffs, spearheaded by Rep. William McKinley (R-Ohio), who in 1889 was appointed Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee and so lent his name to a new tariff the following year. The McKinley Tariff brought in new protective duties on imported goods, to the tune of nearly 50 percent in some cases. Democrats regained control of Congress and the White House in the 1892 elections and then, two years later, brought in the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act, which sent tariffs lower again, to a still-rather-high 42 percent. McKinley remained a prominent figure on the national stage and was the Republican presidential standard-bearer in 1896. He won that election and, with a strong Republican presence in Congress, in 1897 implemented the Dingley Tariff (named for Rep. Nelson Dingley, Jr. (R-Maine)), spiking rates again. Additions to the raft of duties were hides and wool, which had been duty-free for some years by that time. The top rate was 52 percent, the highest in American history. Republicans continued to favor tariffs as the primary means of revenue generation, and subsequent Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft maintained that stance. However, an attempt for even greater protectionism severed the Republican coalition in Taft's first year in office. The 1909 Payne-Aldrich Tariff (named for Rep. Sereno Payne (R-N.Y.) and Nelson Aldrich (R-R.I.)) introduced a couple of new wrinkles: a tariff board and free trade with the Philippines. Among the provisions of the Payne-Aldrich Tariff was an increase in the tariff on print paper; newspapers publishers certainly didn't appreciate that and turned on Taft and the Republican establishment in a big way. As well, Progressives, by then making up a large part of the Republican Party, found the tariff a bridge too far. Former President Teddy Roosevelt seized the moment, created a new political party, and himself ran for the White House in 1912. One smaller element of the Payne-Aldrich Tariff that foreshadowed future events was the creation of an income tax on corporations. As early as 1909, Taft had proposed a constitutional amendment to provide for the Government's ability to implement an income tax on individuals and an excise tax on businesses. The latter became the Corporation Tax Act of 1909, which stipulated a tax of 1 percent, after an exemption of $5,000. Such an idea wasn't at all popular with such businesses, and a legal challenge ensued. That challenge ended in the Supreme Court, in the 1911 case Flint v. Stone Tracy Co., in which the Court upheld the legality and validity of such a tax. A Congressional amendment to the 1894 Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act had brought back the iindividual income tax, on annual incomes higher than $4,000. But a Supreme Court decision that same year, Pollock v. Farmer's Loan & Trust Co., declared this kind of tax unconstitutional. Taft's other idea, a resurrection of the individual income tax, became the 16th Amendment, enacted in 1913: "The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration." That wasn't the end of tariffs, though. They continued, with the Underwood Tariff (named after Rep. Oscar Underwood (D-Ala.)), which cut tariffs across the board, from 40 percent to 26 percent. This was possible, of course, because of the advent of the individual income tax, made possible by the 16th Amendment and brought into reality by the Revenue Act of 1913, which established a tax of 1 percent on income above $3,000 annually and also a 1-percent tax on all corporate income (removing the $5,000 exemption of the 1909 Corporation Tax Act). The rates of the Underwood Tariff were deemed sufficient during World War I. The Elections of 1920 brought in a Republican majority in Congress and a Republican in the White House, in the form of Warren G. Harding, and one prime piece of legislation was another tariff, the 1922 Fordney-McCumber Tariff (named for Rep. Joseph Fordney (R-Mich.) and Sen. Porter McCumber (R-N.D.). As the countries of Europe were rebuilding after the world war, the U.S. extended large loans to many of them, at the same time implementing new tariffs. The result this time was considerably hostile, as European nations instituted tariffs of their own. Spain targeted American goods specifically, introducing a tariff of 40 percent. France bumped up its tariff on cars from 45 percent to 100 percent; this hit the U.S., a major car manufacturer, hard. Also hit hard were American farmers, as both Germany and Italy increased their wheat tariffs.

The bottom fell out of world markets in 1929, punctuated by the Stock Market Crash in that year, and the Great Depression ensued. Congress chose to confront the multilateral problem in a variety of ways, one of which was yet another duty (even with the trade war consequences of the Fordney-McCumber Tariff still being felt). This was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 (named for Rep. Reed Smoot (R-Utah) and Rep. Willis Hawley (R-Ore.), which brought in tariffs exceeded only by the 1828 "Tariff of Abominations." One justification for the introduction of the tariff was that the American economy had not been affected as severely by the war and so was suffering from a bit of overproduction, now that the war had ended, and so the idea was to stimulate the purchase of American goods because they were effectively cheaper than foreign goods, which were burdened by the tariffs. The League of Nations had, as early as 1927, strongly urged the countries of the world to abandon a tariff-first policy, especially since many European countries had yet to dig themselves out of the economic hole into which the war had buried them. Ignoring that advice first was France, which instituted new tariffs the following year and then the U.S., with the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, two years after that. The result on the world stage was yet more tariffs, from other countries, including even Canada, America's most loyal trading partner. In the same year of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, Canada slapped on American goods a duty of 30 percent. European countries followed suit. With the country (and, indeed, the rest of the world) in the grips of the Great Depression, a resurgent Democratic Party seized control of Congress (with a very large majority) and the White House (in the form of Franklin D. Roosevelt). With the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, the President gained the power to conduct tariff negotiations country-to-country. Significantly as well, such agreements were to take the form of a regular law, rather than a treaty; the result was that such agreements could be approved with a simple majority of Congress, whereas treaties required two-thirds approval. Roosevelt and Congress lowered tariffs across the board. As the U.S. slowly climbed out of the Great Depression, World War II began. Despite the massive death tolls and atrocities committed during that war, many economists have argued that, as during World War I, the advent of armed conflict played a large part in America's recovering from the effects of the great economic downturn. At any rate, the coming of the United Nations brought with it an appetite for multilateral trade agreements. One prime mover of that was the General Agreement on Trades and Tariffs, begun in 1947. Its successor the World Trade Organization arrived in 1993. The U.S. has been an important member of both the GATT and the WTO. Nonetheless, tariffs still exist. The percentage of imported goods that are so taxed is much lower than in times past. Relatively recent alternative strategies have included a quota, or import limit (on goods from a particular country, say). One amusing-sounding but quite serious trade dispute in the 1960s was the "Chicken War," a multilateral struggle over the consumption of meat. The U.S. Government had rationed the consumption of red meat during World War II, prioritizing consumption by the armed forces; and accompanying that rationing was a homefront campaign to encourage a greater consumption of poultry and fish. American factories increased their production of chicken, which lowered the price. Fast forward to 1962, when members of the European Economic Community (the forerunner of the European Union) instituted tariffs on chicken imports from the United States. No fewer than six European countries (Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany) increased their chicken tariffs, resulting in a drop in U.S. poultry exports. After a number of months of economic pain, President Lyndon B. Johnson imposed reciprocal tariffs on imports of brandy, potato starch, dextrin, and high-end trucks. Tempers eventually cooled. In the 1980s and 1990s were determined efforts to pursue free trade policies. Unlike the Republican Presidents of a century before, both Ronald Reagan and >a href="/subjects/georgebush.htm">George Bush strove to hew to GATT and WTO anti-protectionist policies, although Reagan notably imposed tariffs of 100 percent on Japanese imports during his second term. Reagan was President when the U.S. negotiated the Canada–U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1987, and Mexico joined in that arrangement with the North American Free Trade Agreement (1994), begun under Bush and finished off by President Bill Clinton. One notable exception to this philosophy came in 2002, when President George W. Bush slapped tariffs on imported steel. (He removed them a year later.) President Donald Trump, in his first term, negotiated an update to NAFTA, technically, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement and referred to by many as NAFTA 2.0 or New NAFTA. The new agreement is basically an update of the previous one, with additions to cover newer items like digital trade and intellectual property. It is still a free trade agreement, with a 14-year term. Also in his first term, Trump instituted tariffs on all washing machines and all solar panels, targeting China, the world's leading producer of the latter. Trump widened the attack on China with a 25-percent tariff on hundreds of Chinese products; naturally, China responded, with a tariff on U.S. sorghum, soybeans, and airplanes. Trump, too, placed a tariff on steel, adding one on aluminum, in the latter case targeting Canada and Mexico, as a form of protection of American jobs; Canada responded with a wide variety of tariffs on American imports. Joe Biden kept in place the solar panels tariffs but let the washing machines tariff fall away. Trump, early in his second term, implemented a 10-percent tariff on all Chinese goods and threatened similar tariffs on Canada and Mexico, in an echo of his first term strategy. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2025

David White