Charles V: Holy Roman Emperor and Spanish Monarch

Part 3: Final Years

European explorations in the New World were many at this time. The most famous might have been that of Ferdinand Magellan, who set out to circumnavigate the globe. Magellan couldn't convince his own monarch, Portugal's King Manuel I, to finance such a mission, but Charles saw the merit in it and provided ships and financing. Magellan did not complete his voyage, but one of his ships did.

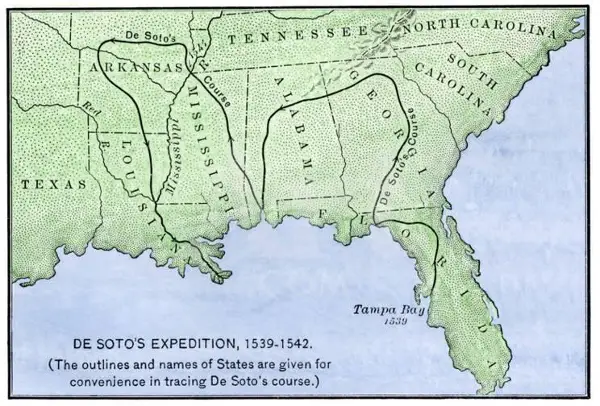

In 1536, Charles V gave Hernando de Soto the royal imprimatur for an expedition to North America, to explore La Florida, what is now the southeastern U.S. The base for this expedition was Cuba, of which de Soto was made governor. An expedition of about 600 men, they set out in May 1539. They traveled through what is now Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas. They crossed the Appalachian Mountains and explored the Tennessee River Valley. The first Europeans to see the Mississippi River, they crossed it but didn't go up or down it. They didn't find the gold that they were seeking. Another well-known mission supported by Charles V was that of Juan Ponce De Leon, who went in search of the Fountain of Youth and found Florida instead. A related development was Charles's decision in 1518 to start sending enslaved people directly from Africa to the New World, rather than stopping in Europe (Spain, in this case) on the way. He was the first monarch to do so. In this way, as with the conquests of the Mesoamerican and South American empires, Charles swelled the royal coffers.

After many years of conflict and strife, Charles abdicated the Holy Roman Empire throne, enabling his younger brother Ferdinand to assume the position. (Ferdinand had ruled the Austrian lands since 1521.) By the time of the abdication, Charles had married and buried his wife, Isabella of Portugal. Charles had originally sought a marriage with Mary, the sister of England's King Henry VIII and, subsequently, Henry's own daughter (also named Mary), but the two rulers never worked out the details to either's satisfaction and Charles decided instead to marry closer to home. Isabella was the daughter of King Manuel I of Portugal and, as such, was Charles's first cousin. By the time that Charles had decided to get married, her brother, John III, was on the Portuguese throne. Charles agreed that John would marry Catherine, Charles's sister, in exchange.

Charles and Isabella had not met until March 10, 1526, by which time their marriage had already been arranged. The couple fell in love instantly and were married that night. The very next year, the emperor-monarch ordered the beginning of construction on the Palace of Charles V; neither he nor his wife lived to see its completion.

Isabella died in 1539. Charles was devastated by his wife's death, shutting himself up in a monastery for a time to grieve. He wore black for the rest of his life in her honor. He commissioned the famous Italian artist Titian to create a handful of paintings in Isabella's honor and also commissioned the Flemish composer Thomas Crecquillon to write a new musical piece to memorialize the queen. Isabella was pregnant when she died. Of her previous six births, three survived into adulthood:

Charles announced his abdication in 1556, but bureaucratic technicalities delayed its taking effect for two years. He had given up his Spanish throne at that time, and that is when his son Philip became king. Charles spent his last days in the Monastery of Yuste, in Extremadura. He fell ill from malaria in August 1558 and died on September 21 of that year. He was 58. First page > Setting the Stage > Page 1, 2, 3 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Charles was very much a fan of

Charles was very much a fan of