The Conquest of the Inca

At its height, the Inca Empire was the largest in South America, certainly, and one of the largest in the world, in terms of geography. From beginnings in the 1200s, the Inca rose to prominence, conquering neighboring civilizations. By 1438 and the rule of Cápac Inca Pachacuti, the Inca reigned supreme for thousands of miles. Less than 150 years later, the Empire was no more.

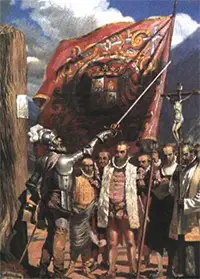

The Inca Empire had a central government dominated by one man, the supreme ruler. It was under the leadership of Pachacuti's grandson Huayna (right, who reigned for several years on either side of the advent of the 16th Century) that the Inca Empire reached its greatest power. Inca armies spread throughout the Empire, patrolling the roads and villages, blandishing weapons and keeping the peace. All of that was immaterial when they came up against the Spanish, who spewed a wide array of devastation: more deadly weapons, more determination to kill and conquer, and more deadly diseases. By that time, Spanish explorers and conquistadores had reached the Inca realm. As these invaders did with the Aztecs, they brought with them a handful of diseases that proved lethal to the Inca, who had no immunity to such things. Smallpox killed thousands of Inca, including Huayna himself, in 1525. The death of Huayna ignited a struggle for control, with two of his sons, Huascar and Atahualpa, claiming leadership. For several years, a civil war raged. Atahualpa emerged victorious, claiming victory in 1532. This was the same year in which the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro arrived at the center of Inca lands. He and a Spanish contingent that included four of his brothers had first encountered elements of the Inca Empire four years earlier, in the far north. After a handful of expeditions, they had arrived with dread purpose. Huascar was Huayna's designated heir; that didn't stop Atahualpa from laying claim to the throne anyway and vowing to fight to claim it. Atahualpa proved more able to convince others to fight with him, and he conquered much of the land surrounding Cuzco, the capital, before claiming that as well, defeating his brother and claiming the throne. Francisco Pizarro had arrived in South America with a mission: to conquer what is now Peru. He arrived in Inca lands and sent an emissary, Hernando de Soto, to meet with the newly ascendant Atahualpa, who was celebrating his victory at Cajamarca. De Soto's task was to convince the Inca ruler to meet with Pizarro. Atahualpa, awed by the horse on which De Soto sat (for the Inca ruler had never seen one), agreed and, with a contingent of soldiers, went to the meeting, on Nov. 16, 1532.

Pizarro was also on a mission of conversion. He told Atahualpa all about Christianity, trying to convince the Inca leader to convert. According to one story, Pizarro handed Atahualpa a Bible, saying that it held all wisdom. Atahualpa, having never seen a book, put it up to his ear, listening for an answer. When he heard nothing, he threw the Bible to the ground. It was then that Pizarro instructed his main force of soldiers to attack. The Inca force numbered 6,000; not suspecting a confrontation, they had arrived unarmed. Including Pizarro, the Spanish forced numbered 169. But the Spanish had several dozen soldiers on horseback, and the Spanish soldiers had guns and other weapons that were technologically advanced compared to what the Inca soldiers wielded. The number of Inca dead that day exceeded 2,000. Pizarro ordered Atahualpa captured. The Inca ruler offered a large amount of gold and silver as a ransom. In fact, he offered to fill a room with gold and then fill two rooms with silver if the Spanish would let him go. Pizarro accepted the precious metals but then refused to release his prisoner. He ordered Atahualpa kept hostage for a few months and then, on Aug. 29, 1533, ordered him killed, directly after giving him a Christian baptism. Pizarro and his men had also arrived at a time in which Inca people by the hundreds and thousands were dying of smallpox and other killers. European explorers had ranged throughout the continent, unwittingly spreading dread diseases in their wake. The combination of the killing efficiency of these diseases and the overwhelming advantage in weaponry that the Spanish sported led to the demise of the Inca Empire.

In the wake of the destruction of Cuzco, Pizarro ordered built what is now Lima, in 1535. While construction on that city continued, the Inca put up a spirited defense. Manco Inca, whom Pizarro had installed as a puppet emperor, revolted and led the resistance, seizing some Spanish territory and centralizing his efforts at what he proclaimed to be a new capital, Vilcabamba. He fought on, meeting his death in 1544. By that time, the Spanish leadership had fragmented. Arriving with Pizarro as one of the leaders of the expedition had been Diego de Almagro. A disagreement between the two led to a parting of the ways and then a severe enmity. Hernando Pizarro, Francisco's brother, killed de Almagro in 1538. Three years later, de Almagro's son killed Francisco Pizarro. Hernando was unable to take advantage because he had been taken prisoner after returning to Spain to lobby the king and queen for support. Inca resistance continued in Vilcabamba for another 30 years, as the Spanish ruled more and more of what had been the Inca Empire. Spanish troops captured the last Inca ruler, Tupac Amaru, in 1572. The last resistance crumbled, the last remaining Inca surrendered, both Vilcabamba and overall, and the Spanish conquest was complete. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White