New Spain

Part 3: High and Lows and the End

Spanish officials envisioned a highly structured system of governance for Alta California. They had built the missions with the idea of spreading Christianity throughout the new land, and missionaries aimed to convert Native Americans to the Christian faith while also teaching them trades like brickmaking and blacksmithing. At a higher level, Spain divided Alta California into four military districts, with each one having a presidio acting as a controlling interest. Spain built the other three presidios at Monterey, San Francisco, and Santa Barbara.

Commanding later Spanish expeditions were Gaspar de Portola and Juan Bautista de Anza. Spanish settlers also founded towns, many of them. What is now the largest city in the State of California, Los Angeles, was established in 1781; San Jose, in the north, had come along four years earlier.

The Spanish built missions in what is now Texas throughout the 18th Century, including the Mission San Antonio de Valero in 1718. Also set up during this time were the towns of Goliad, Nacogdoches, and San Antonio. Spanish settlement increased throughout the area, and conflicts between Spanish and Native Americans were not uncommon. Parts of northern Texas were included in the Louisiana Territory, which was owned by France originally, then went to Spain in 1762, then went back to France in 1803, then ended up with the United States as part of the Louisiana Purchase. The United States at this time insisted that the Louisiana Territory included all of Texas; Spain disagreed. The 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty sorted this out, with the U.S. renouncing all claims to Spain in exchange for Spain's agreeing to the American takeover of Florida. When the 13 Colonies of the United States revolted against Great Britain, Spain waited a few years and then threw in their lot with the Americans, fighting British troops in the Gulf Coast area in 1779–1781. The 1783 Treaty of Paris, ending the American Revolutionary War, gave Florida back to Spain.

The reach of New Spain extended across the Pacific. In the same year that St. Augustine was founded, Miguel López de Legazpi led an expedition that founded the town of San Miguel on the Philippine Islands (named for King Philip II). Trade between the Philippines and Acapulco flourised, and Manila became the capital of the Spanish East Indies, which at its greatest extent included the Caroline Islands, the Mariana Islands, the Marshall Islands, Palaos, and parts of Formosa and the Molucca Islands and Sulawesi. (The West Indies, of course, were the first Spanish possessions in the New World: Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, and other Caribbean lands.) Acapulco, Manila, and Veracruz became the main trade centers of New Spain, sending wave after wave of goods and money back to the Spanish homeland. Among the goods sailing eastward across the Atlantic Ocean were cacao, indigo, and a red dye known as cochineal.

Trade ships traveled in convoys, to protect against attacks by pirates and other rivals. England's Sir Francis Drake famously raided a Spanish convoy in 1580, and his compatriot Thomas Cavendish did the same seven years later. Closer to home, the Viceroy Don Lope Díez de Armendáriz (the first of his title to be born in the New World) set up a system of coastal patrols, based in Veracruz. Silver was a primary export from New Spain, from mining centers like Hidalgo and Zacatecas. As monarch after monarch struggled to finance various war efforts through taxes and other internal revenue-raising means, silver poured in to Crown coffers from the New World. Working in those mines were mainly forced laborers. The slave trade supplied a significant portion of this labor. Spanish rulers and soldiers still had a large amount of weapons and ammunition in the early 19th Century. What the lower three classes had was a large number of people who were increasingly expressing a passion for going their own way. Inspiring them was the Virgin of Guadalupe, an indigenous patron saint whose skin color was not white. Depictions of her appeared on banners borne by those in rebellion.

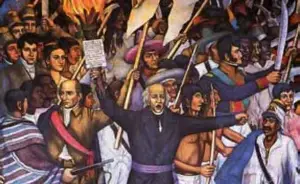

The first significant event in the drive toward Mexican independence was a call from a religious figure. Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, a Catholic priest born in Mexico, urged his parishioners to rise up and throw off the Spanish yoke on Sept. 16, 1810. He made this plea in the town of Dolores, in which he was the priest at the time. This became known as the Grito de Dolores, or "Cry of Dolores." Hidalgo, a well-known theologian, had offered his home as a setting for secret meetings to discuss independence. Among his associates was the well-known military Ignacio Allende. The ground was already laid, and Hidalgo's public call for a revolt was met with enthusiasm by several hundred people right away. Hidalgo made it clear that anyone who wanted to rise up against Spain was welcome in his movement. Members of all of the lower classes joined the movement. Following the lead of Hidalgo and Allende, the group, which numbered about 600 within a few days, set off in search of Spaniards to target. Rebel numbers swelled rapidly; and by the time the force reached Guanajuato on September 28, it was 30,000. Spanish soldiers who had had word of the impending attack had barricaded themselves inside a granary; the mob stormed the granary, resulting in the deaths of more than 500, and continued on to the capital, Mexico City. Skirmishes between ruling and ruled continued, as Spain scrambled to respond to a situation that was rapidly spinning out of control. The next large confrontation was on October 30, at the Battle of Monte de las Cruces. Again, Hidalgo's force emerged victorious, in the process seizing a number of cannons. On the verge of entering Mexico City and pressing his case for the overthrow of the royal governor, Hidalgo decided against such a move. Following Hidalgo's lead, the mob suddenly dispersed, spreading out across the surrounding countryside. Some rebels continued to fight, but the tide had turned. Spanish forces won the Battle of the Bridge of Calderón in January 1811, setting the insurgents on a path of flight. A resurgent Spanish army captured the rest of the rebels, including Hidalgo, in the state of Coahuila. Allende and other soldiers were summarily executed. Hidalgo underwent public humiliation at the hands of the Inquisition and was then killed. The revolutionary spirit was still alive in many Mexicans, however, and José María Morelos, a secular priest like Hidalgo, assumed leadership of the rebellion. In yet another change in momentum, Morelos inspired his forces to take the fight again to the Spanish, succeeding in taking over the large cities of Acapulco and Oaxaca. Looking to find further inspiration for the insurgency, Morelos called a meeting of rebels from various parts of the country. The Congress of Chilpancingo began on November 6, and the result was the Solemn Act of the Declaration of Independence of Northern America. The war continued. Morelos himself was captured in 1815 and, like rebel leaders before him, tried for treason and convicted and executed. The rebellion was fueled by not only the desire for independence but also the memory of Hidalgo and his leadership and martyrdom. The numbers of fighters and weapons on both sides had diminished by this time, and the next few years featured much less military activity but a slight increase in guerrilla fighting on the behalf of the insurgency and yet another new leader, Vicente Guerrero.

A key development came in 1820, when Agustín de Iturbide (right), a Spanish soldier who had helped defeat Hidalgo, switched sides. The Spanish monarch had been overthrown, and many in New Spain thought that they would fare better as an independent entity. Seeking to ensure an orderly transition, the leaders of the rebellion met with Iturbide and other soldiers and agreed on the Plana de Iguala, which set out the blueprint for a new government, a constitutional monarchy independent from Spain that would guarantee political and social equality among all of its citizens. The long civil war ended on September 27, 1821, when representatives of the rebellion and the government signed the Treaty of Cordoba. Iturbide was named President of the Regency and, the following year, was the first Constitutional Emperor of Mexico. The constitutional monarchy had a short life. Another rebellion, led by Antonio López de Santa Anna and Guadalupe Victoria, in 1823 overthrew the emperor and established the Mexican Republic. Spain officially recognized Mexico's independence in 1836. The independence of Mexico meant that the Spanish possessions in what is now the U.S. left the Empire as well. Central America seceded in 1823. For all intents, New Spain was no more. First page > Worldwide Fame > Page 1, 2, 3 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Starting in 1769, Catholic missionaries from Spain built

Starting in 1769, Catholic missionaries from Spain built