Sir Francis Drake: Queen Elizabeth's Most Valuable Sailor

Sir Francis Drake rose from humble beginnings and made a name for himself as one of the most feared or reviled names on the high seas, depending on who was doing the commenting. As with many people in the 16th Century, Drake was born into rather obscure circumstances. He is thought to have been born in the early 1540s, in Devon. His parents are known to Edmund Drake, a farmer, and Mary Mylwaye Drake. The oldest of 12 children, Francis was said to have been named for his godfather.

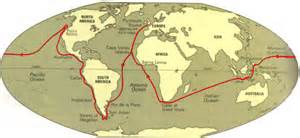

In 1569, not yet 30, Francis married Mary Newman. She died 12 years later, and Francis married again, three years after that, to Elizabeth Sydenham. Neither couple had children. Before he got married, however, he was making a name for himself at sea, first as a slave trader and then as an enemy of Spanish sailors. In his early 20s, Drake sailed to the Americas. England and Spain were at varying stages of conflict for many years during Drake's lifetime, and he and a family friend were trapped by Spanish forces and narrowly escaped. This helped Drake form an enmity for Spanish sailors that he held all his life. In 1572, Drake led a raid on the Isthmus of Panama, which the English called the Spanish Main. The English captured the town of Nombre de Dios and with it, a large amount of gold and other treasures. The following year, Drake was again at the head of a raid on Spanish possessions, and again the result of was English capture of Spanish treasure. After a bit of a struggle getting back, Drake enjoyed recognition from England's queen, Elizabeth I. In 1577, the Queen sent Drake on another mission, to harry the Spanish on the other side of the Americas, along the Pacific coast. After a false start in November, in which they got caught in a storm and had to return to England for repairs, Drake and his men set out on December 13 with a large handful of ships. The expedition lost two ships during the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, before Drake and the surviving ships landed at San Julian, where Ferdinand Magellan had landed a few decades before, in what is now Argentina. They stayed the winter in San Julian, then followed Magellan's route through the strait that now bears his name. Storms again beset the English ships, destroying one and forcing another to return home. The one remaining ship was the one that Drake set out on originally, the Pelican. The remaining ship made it through the Strait of Magellan but had to go farther south because of bad weather. Drake called Elizabeth Island a small strip of land that he discovered there. Turning northward, Drake followed her majesty's orders and attacked Spanish ports and towns on the western coast of South America. As a result of a sea battle, Drake captured some Spanish ships and consulted their charts, which happened to be a bit more accurate than the English ones. He added to his haul by capturing two more ships laden with treasure.

Drake had renamed his ship the Golden Hind along the way, and the crew set out across the Pacific, bound for home. Again following in Magellan's ship-steps, he reached the Moluccas, navigating a lucky escape from a reef by waiting three days for favorable tides to help the ship come unstuck. The Golden Hind sailed onward, round the tip of Africa, round the Cape of Good Hope, and eventually back to England, arriving on September 26, 1580. His voyage was the second to circumnavigate the globe. Queen Elizabeth awarded Drake hansomely, including giving him a jewel with her portrait (which is now called the "Drake Jewel" and resides in London's Victoria and Albert Museum). The following April, Queen Elizabeth knighted Drake, aboard his famous ship. He then served as Mayor of Plymouth and was a Member of Parliament. He bought a large manor in Devon and lived there for 15 years.

When the Armada sailed for England, in 1588, Drake was named Vice Admiral in command of the English fleet. He proved himself up to the responsibility, capturing a large Spanish galleon, the Rosario, and its admiral and crew and then organizing a collection of fire-ships that didn't sink the Spanish ships so much as force them to scatter into the open sea, where they were easier targets for the more maneuverable English ships. The result was the famous Battle of Gravelines, a clear English victory over what Spain had termed an invincible armada. The Spanish fleet headed for home, and Drake and other "sea dogs" were tasked with destroying the remaining ships. He was less successful in this regard and then returned again to Spanish America, where he found even more defeat. He contracted dysentery while anchored off the coast of Portobelo, Panama, and died in January 1596. His body was sent into the sea and has not been recovered. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

Edmund Drake was a Protestant in a time of religious persecution, and in 1549, he took his family to Kent, where he became a minister. Young Francis got himself an apprenticeship to one of his new neighbors, a ship master.

Edmund Drake was a Protestant in a time of religious persecution, and in 1549, he took his family to Kent, where he became a minister. Young Francis got himself an apprenticeship to one of his new neighbors, a ship master. The English sailed up the western coast of what is now North America and put in to land farther north than the northernmost Spanish possession, at a place Drake named Nova Albion (Latin for "New Britain"). It is possible that some of the crew stayed behind to found a colony.

The English sailed up the western coast of what is now North America and put in to land farther north than the northernmost Spanish possession, at a place Drake named Nova Albion (Latin for "New Britain"). It is possible that some of the crew stayed behind to found a colony. In 1585, England and Spain went to war, and Queen Elizabeth sent Drake back out to harry the Spanish, again in the Americas. He sacked Port Domingo, captured a city in what is now Colombia, and devastated a Spanish fort in Spanish Florida. He returned home via Spain and boldly sailed into two of Spain's main ports, Cadiz and Corunna, destroying 37 ships in all and cutting into Spanish supply lines by capturing shipments bound for Lisbon. By this time, Spain's

In 1585, England and Spain went to war, and Queen Elizabeth sent Drake back out to harry the Spanish, again in the Americas. He sacked Port Domingo, captured a city in what is now Colombia, and devastated a Spanish fort in Spanish Florida. He returned home via Spain and boldly sailed into two of Spain's main ports, Cadiz and Corunna, destroying 37 ships in all and cutting into Spanish supply lines by capturing shipments bound for Lisbon. By this time, Spain's