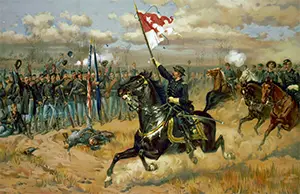

Union General Philip Sheridan

Philip Sheridan was a Union general during the American Civil War. A cavalry commander, he is most well-known for "the Burning," a campaign of devastation that he oversaw in the Shenandoah Valley in the waning months of the war.

He was born on March 6, 1831, in Albany, N.Y. He had various odd jobs while growing up in Ohio and won appointment to the U.S. Military Academy in 1848. After a few difficulties, he graduated, in 1853, and was assigned fo the First U.S. Infantry regiment at Fort Duncan in Texas. He was on duty in Oregon when Confederate troops shelled Fort Sumter and, later that year, found himself assigned to the staff of Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck. A promotion to colonel of the 2nd Michigan Cavalry followed, in May 1862. He first led men into battle at Booneville, in Mississippi, two months later, winning acclaim for his cavalry tactics and intelligence-gathering and a promotion to brigadier general. He played a pivotal role in two other Union victories in 1862, at Perryville and later at Stones River, where he served under Maj. Gen. William S. Rosencrans in his ongoing clashes with Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg. In the ensuing Battle of Chickamauga, a fierce counterattack by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet drove Sheridan and his cavalry out of the fray. They retreated to Chattanooga and played a major part in the October 1863 Union victory there, helping drive the Confederate defenders off Missionary Ridge. Impressed with Sheridan's success, the Union's general-in-chief, Ulysses S. Grant, ordered the cavalry commander to join his force in the East, as the commander of the Army of the Potomac's Cavalry Corps. He reported for duty on April 5, 1864. Sheridan and his cavalry joined Grant's Overland Campaign to Richmond, providing critical intelligence by roaming on reconnaissance missions. They had little chance of being effective in the battle at the Wilderness and then proved unsuccessful at keeping the Confederate army from shadowing the Union army to Spotsylvania Court House. He convinced Grant that he could defeat the vaunted Confederate cavalry commander J.E.B. Stuart and won permission to embark on a road survey of Richmond. For two weeks in May 1864, Sheridan and Stuart traded blows. Sheridan got the technical better of Stuart in that the latter suffered a fatal blow at the Union victory at Yellow Tavern on May 11. But Sheridan's roaming the countryside around Richmond also took him away from his primary responsibility, which was to be the "eyes and ears" of the Army of the Potomac. Grant sent Sheridan back to the Shenandoah Valley in September, to administer to it the kind of treatment that Gen. William T. Sherman was giving Georgia and the Carolinas– total devastation. Sheridan and his 40,000 cavalry and infantry roamed about the Shenandoah Valley more freely than they had ever been able to do before, laying waste to barns, factories, mills, railroads, and other elements of commerce that could aid any sort of Confederate reinforcement. Known as "the Burning," this campaign transformed more than 400 square miles of the Valley into uninhabitable dead space.

This kind of devastation took time, and not all Confederate troops had left the Shenandoah Valley. Gen. Jubal Early was one such commander who had a force still under his command, and these troops launched a surprise attack on Sheridan and his men at Cedar Creek on October 19. Sheridan himself was in Winchester, 12 miles away, at the time of the attack but rode hard back to his men and arrived in time to initiate a counterattack that ended in a Union victory. The Union command promoted Sheridan to the rank of major general. Sheridan took part in the Siege of Petersburg, leading a cavalry raid south of Richmond that culminated in another Union victory at the Battle of Five Forks, on April 1, 1865. Lee surrendered Petersburg the next day. Sheridan doggedly pursued Lee's army, helping to defeat it the Battle of Sayler's Creek on April 6 and then, three days later at Appomattox Court House, blocked Lee's retreat; the Confederate surrender occurred later that day. At Sayler's Creek, Sheridan's men were seemingly everywhere, providing crucial intelligence about the Confederate army's movements and even posing as Confederate soldiers by wearing gray uniforms and then arresting a large contingent of actual Confederate troops. During Reconstruction, Sheridan was the military governor of the Fifth District, encompassing Louisiana and Texas. Already known as a taskmaster, he proved so demanding a governor that President Andrew Johnson relieved him of his position. Sheridan accepted an assignment in the West in 1867. His job was to put down what was a growing number of uprisings by Native Americans who were unhappy with the growing number of settlers moving west. Sheridan used the same devastation tactics that he had used against the Confederate army during the Civil War. During the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, Sheridan oversaw relief efforts by the Army; he was the commanding officer when Mayor Roswell Mason declared martial law to keep the peace. He married Irene Rucker in 1875; they had four children. He became the top general in the Army on 1883 and achieved the tank of General of the Army of the United States, following in the footsteps of Grant and Sherman. Also in the last two decades of his life, he went to great lengths to keep what became Yellowstone National Park from being taken over by developers. He died on Aug. 5, 1888 at Nonquitt, Mass., after a number of heart attacks. He had just completed his memoirs, which were published after his death. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White