The Battle of Petersburg

The Battle of Petersburg was the last major battle of the American Civil War. Punctuated by a monthslong siege, the battle ended in a Union victory and, a week later, the surrender of Confederate top commander Robert E. Lee and effectively the end of the war.

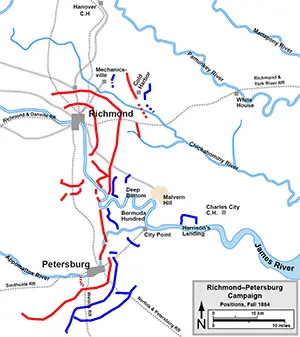

After a futile attempt to dislodge the Army of Northern Virginia at Cold Harbor in early June 1864, the Union's top commander, Ulysses S. Grant, ordered the Army of the Potomac to again head toward Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. Lee certainly thought that Grant was finally going to attack Richmond. Grant's target, however, was Petersburg, a city 23 miles to the south of Richmond that was a vital railway junction, connecting the capital to the north and North Carolina, in which was still open the port of Wilmington. In a rare success, the Union command outfoxed the Confederate command and, on June 12, got its troops across the James River unopposed and on the road to Petersburg, erecting a 2,100-foot-long pontoon bridge to do so. On June 15, the first fighting began. At this time, most of the Confederate force was elsewhere. Defending Petersburg were a few thousand troops under the command of Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard. Attacking those troops on June 15 were 10,000 Union troops from Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler's Army of the James, under the command of Gen. William Smith. Butler had attacked the city on June 9, before Grant and his troops began their move south, but had been repulsed. They got another chance six days later.  The fortifications at Petersburg were extensive, and the smaller defending force held off the larger attacking force, despite the latter having some temporary successes. Lee, racing back to Petersburg with the Army of Northern Virginia, arrived and began to add his troops to the city's defense, both on patrol and in building further fortifications. On June 16, the numbers were still very much in the Union's favor, with 50,000 troops ready to face off against 14,000 Confederate troops. Attacks by a force under Ambrose Burnside and Winfield Scott Hancock did little damage to the defenders and, after fierce counterattacks, were called off. By June 18, the Union force ringing Petersburg approached 67,000 men in strength. By that time, however, a number of subsequent futile attacks resulting in casualties exceeding 11,000 had convinced Grant that a full-scale assault on the city would result in nothing more than added bloodshed with no purpose. The Union soldiers dug trenches around the city and settled in for a siege. They didn't entirely surround the city, though. Meanwhile, Union troops elsewhere were doing damage to the lines of the three remaining railways that led into Petersburg. If Petersburg could still be accessed by rail, then it could more easily gain reinforcements of men, food, and weapons. To the vital port of Wilmington, N.C., led the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad. Repeated cavalry and infantry attacks on the Confederate troops defending the Jerusalem Plank Road, which ran parallel to Petersburg to the south and ended at the north-south Petersburg and Weldon Railroad line, failed to dislodge the defenders. Union casualties numbered nearly 3,000; Confederate casualties were just under 600. However, the already outmanned Confederate defenders had had to spend energy and manpower in extending the fortifications away from the main line at the city of Petersburg. As had often been the case during the Civil War, the Union always seemed to have more men, money, weapons, and time. Targeting the Richmond and Danville Railroad were troops of the Army of the Potomac under Brig. Gen. James Wilson. This attack force was more successful, ripping up miles of track on that line, but eventually had to retreat in the face of a stronger-than-expected Confederate resistance and the lack of reinforcements that had been expected from the troops along Jerusalem Plank Road. To the north of Petersburg, on the way to Richmond, was Deep Bottom. On July 27, after a month of skirmishes and feints and waiting in trenches, Grant ordered a force of cavalry and infantry north to Deep Bottom. Heading up the cavalry was Philip Sheridan, who had orders to ride all the way to Richmond if the accompanying infantry could pave the way. Commanding the infantry was Hancock. Sheridan's secondary goal, should an attack on Richmond seem impossible, was to destroy the tracks of the Virginia Central Railroad, which ran west from the capital to the Shenandoah Valley. The Union force making this journey was significant enough that Lee ordered a reinforcement of Richmond, pulling troops from the south. The Confederate troops arrayed at Deep Bottom and in the surrounding area were enough to deter both Hancock's infantry and Sheridan's cavalry, and all attacks ceased on July 29. The Union army's primary reason for ordering the attack on Deep Bottom, as well as other attacks in the surrounding area, were to force the Confederate troops to thin–or at least geographically extend–the defense of Petersburg. Grant knew that a prolonged siege would be difficult for his troops as well. He had learned that as commander of the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863. With this in mind, he had, in late June, approved a plan to dig a tunnel underneath the Confederate defenses, plant explosives, and then set them off, using the resulting distraction as cover for a fierce attack that he hoped would break through Petersburg's vaunted defensive fortifications. By the end of July, the 20-foot-deep shaft was 511 feet long and was underneath Elliott's Sailent, a fort right in the middle of the First Corps defensive line. At the end of the shaft was a large chamber that housed 8,000 pounds of explosives. The troops detonated the charges at 4:44 a.m. on July 30. The result was a resounding explosion that shattered everything in its surroundings, killing hundreds of Confederate soldiers, blowing to bits their guns and fortifications, and creating a crater that was 170 feet long, 30 feet deep, and up to 80 feet wide. What happened next came to be called the Battle of the Crater. Also fighting for the Union at Petersburg were members of the United States Colored Troops (UCST). Members of this African-American contingent of soldiers first saw action in the West in 1862. At Petersburg, they entered the fray time and again, most notably in the initial assault before the siege began and then during the Battle of the Crater. They were not the first to storm in after the explosion, however. That had been the plan, and Burnside had trained a division of UCST soldiers for the task at hand. Army of the Potomac Commander George Gordon Meade refused to countenance the attack, fearful of the political repercussions if the African-American soldiers were victims of wholesale slaughter. Grant agreed and put out a call for volunteers. After receiving none, he ordered Burnside to solve the problem and he ordered his three commanders to draw lots. The men in the "winning" commander's division were not African-American; they had also not trained, either for the mission or for much fighting at all. Compounding the problem, their commander did not give them specifics on what to do once the explosion once off and, once it did, was incapacitated. With both sides settled again into fortification and trench positions, the waiting continued. Grant authorized another attack on Deep Bottom in mid-August. Lee again sent reinforcements to intercept. After six days of on-and-off-again skirmishes, the Union troops went back south. Not long afterward, Union troops were successful the second time around at neutralizing the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad. It wasn't without a fight, but Union troops under Gen. Gouverneur Warren succeeded in driving off the Confederate defenders at Globe Tavern and did enough damage to the railroad that it ceased being of use to the defenders at Petersburg. A subsequent Confederate victory at Reams Station was successful in driving the Union troops back to Petersburg, but the damage to the railroad was done. Skirmishes continued into September and through October, and then both sides settled in for the winter. A brief battle at Hatcher's Run in February 1865 was inconclusive. However, the winter, the lack of reliable supply lines, and the length of the siege had taken its toll on the Confederate army. In March 1865, the number of Union troops in the area of Petersburg and Richmond was about 125,000. More were on the way. In the Shenandoah Valley but, having finished operations and returning, was the cavalry commander Sheridan, along with 50,000 more troops. Also soon to converge on the area was Gen. William T. Sherman at the head of another large force, the one that had taken Atlanta and gone on the "March to the Sea" and had laid waste to the Carolinas. By contrast, Lee had a force of 50,000 that still had fighting spirit but was weakened by disease and a lack of food and other supplies; as well, the desertions from the Confederate army had begun to rise. Lee devised an attack to be led by Maj Gen. John Gordon that was to break through the Union lines. The location for this was Fort Stedman, and the attack, on March 25, succeeded for a time, punching a 1,000-foot-long hole in the Union line. However, the Union army, which had been planning an attack of its own, soon recovered and punched back with devastating force, opening up on the Petersburg defenses with every piece of heavy artillery it had. Gordon and his men, their numbers dwindled significantly, retreated.

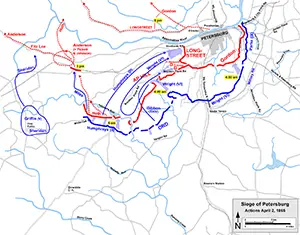

Sheridan and his cavalry had returned by the end of March, arriving from the west. Lee sent nearly 10,000 men under Maj. Gen. George Pickett to Five Forks, to protect that town and its accompanying Southside Railroad. Sheridan and his men easily won the Battle of Five Forks, on April 1. Pickett wasn't even there on the day of the battle and was relieved of his command. The following day, Grant ordered a mass assault on the Confederate line. Union troops made the kind of progress that they had hoped to make many months earlier, forcing the defenders back to the inner ring of fortifications. While riding between the lines to encourage the defenders, Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill, one of Lee's most trusted and longest-serving commanders, fell to Union bullets. Darkness stilled the guns for the day. On that same day, however, Lee had informed Confederate President Jefferson Davis and the rest of the government that he was leaving Petersburg. Evacuations were taking place even as other defending troops were fighting to protect them. The Union occupied Petersburg at dawn on April 3 and Richmond at the end of that same day. Total casualty figures for both armies vary by source. Totals for June 1864, during the initial period of Union assaults, are thought to exceed 11,000 for the Union and 4,000 for the Confederates. Casualties during the siege period are thought to have been 42,000 for the Union and 28,000 for the Confederacy. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

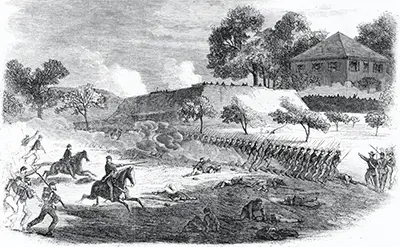

Thus, the fierce attack of Union troops began 10 minutes late. The invaders got through the defenses unopposed because those defenses had largely been blown to bits. However, unlike the UCST troops, who had been told specifically to avoid the crater, the advancing untrained white troops went down into the crater. They had no means of getting back out of the crater, since they were not supposed to be in it and so had not brought ladders of any other means of egress. Confederate troops arrived and began mowing down the Union troops trapped below. Burnside ordered reinforcements from the USCT. In the confusion, more Union soldiers, attempting to avoid flanking fire, found themselves trapped in the crater. More slaughter ensued, as more Union troops entered the fray. Some Union troops bypassed the crater and attacked a fortification, resulting in hand-to-hand combat that lasted several hours. A Confederate counterattack forced the Union troops to retreat. At the end of the day, 504 Union soldiers lay dead, 1,881 were injured, and 1,413 were captured or missing; Confederate totals were nearly half that. The Battle of the Crater was a disaster for the Union. A large part of the UCST troops had died anyway, without much chance of defending themselves. The explosion had created an opportunity that had not been realized. Grant relieved Burnside of his command.

Thus, the fierce attack of Union troops began 10 minutes late. The invaders got through the defenses unopposed because those defenses had largely been blown to bits. However, unlike the UCST troops, who had been told specifically to avoid the crater, the advancing untrained white troops went down into the crater. They had no means of getting back out of the crater, since they were not supposed to be in it and so had not brought ladders of any other means of egress. Confederate troops arrived and began mowing down the Union troops trapped below. Burnside ordered reinforcements from the USCT. In the confusion, more Union soldiers, attempting to avoid flanking fire, found themselves trapped in the crater. More slaughter ensued, as more Union troops entered the fray. Some Union troops bypassed the crater and attacked a fortification, resulting in hand-to-hand combat that lasted several hours. A Confederate counterattack forced the Union troops to retreat. At the end of the day, 504 Union soldiers lay dead, 1,881 were injured, and 1,413 were captured or missing; Confederate totals were nearly half that. The Battle of the Crater was a disaster for the Union. A large part of the UCST troops had died anyway, without much chance of defending themselves. The explosion had created an opportunity that had not been realized. Grant relieved Burnside of his command.