The Surrender at Appomattox

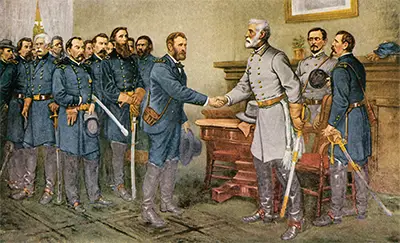

The surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee to Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865, effectively ended the American Civil War.

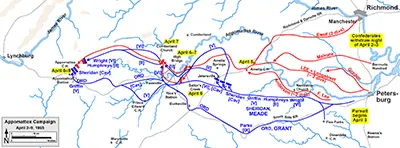

Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia had retreated from Petersburg after the hard-fought battle there, and Grant and the Union armies had seized not only Petersburg but also, the following day, Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. Lee was on the move, hoping to meet up with Gen. Joseph Johnston and his troops in North Carolina. His men arrived at Amelia Court House on April 4; looking for food and weapons, they found only weapons. In desperation, the Confederate troops took the countryside in search of food, begging the local populace to help them. In pursuit and eventually overtaking Lee's army was Union Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan and his cavalry. The two armies clashed on April 6, at Sayler's Creek. The result was a resounding victory for the Union; losses for Lee totaled one-quarter of his army, and among those were a handful of generals. The remaining Confederates marched on, headed for Appomattox Station and what they hoped were supply trains. Arriving in the town ahead of Lee's army was another Union cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer, who ordered his men to burn the supply trains that Lee's army so desperately needed. The Confederate army arrayed itself at the small settlement of Appomattox Court House. The Union cavalry under Sheridan, who had just arrived, blocked one approach out of town, and Grant had sent three corps of infantry on a hurried march to join Custer's cavalry. At first light on April 9, Confederate troops under Maj. Gen. John Gordon attacked the Union cavalry and, pushing back the first line, found themselves face-to-face with Union infantry. Realizing that his army was far outnumbered and effectively trapped, Lee rode out with a handful of aides to request a meeting with Grant. The two commanders traded messages for a few hours and then met at the home of Wilmer McLean. Lee, arrayed in his finest dress uniform, arrived first. Grant, who had been suffering from a severe headache, arrived in a field uniform stained with mud. The two men traded stories about the Mexican-American War, in which they had both fought, and then discussed terms of surrender. In accordance with the substance of my letter to you of the 8th inst., I propose to receive the surrender of the Army of N. Va. on the following terms, to wit: Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate. One copy to be given to an officer designated by me, the other to be retained by such Grant offered to release all of Lee's soldiers, giving them leave to return to their homes without facing the prospect of capture or imprisonment, provided that they leave behind all of their army-issued weapons; in addition, Lee gained the addition of allowing his men to take their horses and mules with them (because unlike the Union soldiers, the Confederates owned their horses and mules and, more likely than not, needed those animals on the farms to which they were returning). Grant also told Lee that Union troops would supply their Confederate counterparts with rations for every remaining soldier. Grant discouraged his men from cheering, reminding them of the terrible cost already paid by those who had gone before them. Representatives from both parties hammered out the details of an official surrender ceremony. Two days later, on April 11, the more than 27,000 remaining in the Army of Northern Virginia officially surrendered to Union troops under the watchful eye of Maj. Gen. Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, who had led the Union defense of Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. As agreed, the Confederate troops left for their homes. Once Lee's surrender became known to the remaining Confederate commanders, they followed suit. Johnston surrendered to Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman on April 26. The final skirmish of the war, near Brownsville, Texas, took place on May 12–13. (It was a rare Confederate victory, followed by a Confederate surrender.) The last surrender came in June. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.

officer or officers as you may designate. The officers to give their individual paroles not to take up arms against the Government of the United States until properly exchanged, and each company or regimental commander sign a like parole for the men of their commands. The arms, artillery and public property to be parked and stacked, and turned over to the officer appointed by me to receive them. This will not embrace the side-arms of the officers, nor their private horses or baggage. This done, each officer and man will be allowed to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by United States authority so long as they observe their paroles and the laws in force where they may reside.