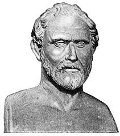

Demosthenes: Famed Orator of Ancient Greece

The most famous and revered orator from Ancient Greek times was Demosthenes, who lived in the Golden Age of Greece and made his home and fame in Athens.

He was born into a wealthy family in 384 B.C.; he was 7 when his father died, and the inheritance was not a large one because his guardians–two of his brothers (Aphobus and Demophone) and a friend named Therippides–spent most of the fortune before Demosthenes came of age. That misfortune created in the boy a strong desire to make his guardians pay, legally, and so spurred him to study the law. Demosthenes had a slight physique and concluded that he didn't have much of a future in athletics or the military. He also had, according to the Greek biographer Plutarch, a speech defect, for which he shut himself away in order to overcome. This gave rise to the familiar yet possibly fanciful story that he learned how to speak clearly and loudly by putting pebbles in his mouth and by practicing before a mirror or by trying to speak over the roar of the waves. Another story relates how he built up his speaking stamina by reciting verses while running. Demosthenes successfully brought suit against Aphobos, his brother, and won a decision at court; what was left of the inheritance by that time, however, wasn't much. He won decisions against two other guardians as well, but again the payout was minimal. What he did gain through these trials was experience speaking in front of an audience. He parlayed this experience into a job writing speeches for other people who had to go to court. In those days, anyone who brought a suit or was sued had to speak for themselves before the judges or the Assembly. Demosthenes became known as both a powerful orator and a talented speechwriter. (The Greek term was logographer.) In 354, when he was 30, Demosthenes made his first major speech before the Assembly. The Ecclesia, as it was also known, had gathered to decide what to do in the wake of a possible threat from the Persian Empire. Demosthenes' speech, titled "On the Navy Boards," helped persuade the Assembly to authorize a buildup of naval forces and also provided a means to pay for it–by taxing the rich. This was more than 120 years after the Greek victory in the Greco-Persian Wars and 50 years after Athens' defeat in the Peloponnesian Wars. Persia was again asserting its dominance in the Mediterranean. Just a year before Demosthenes delivered his navy speech, Athens had agreed to peace with Persian Emperor Artaxerxes III; the agreement required Athens to remove its forces from Asia Minor. Athens had also, dating to 359 B.C., struggled against Macedon. The new king of that area, Philip II, was set on expansion and built up a large army to help facilitate it. Sensing that Philip wanted to absorb more and more Greek territory, Demosthenes set out to oppose him by speaking out in the Assembly. In a series of powerful speeches that historians later called the Philippics, Demosthenes warned against any sort of alliance with or deference to Philip.

Macedon had seized control of the city of Olynthus, which had appealed to Athens for help; the Assembly, despite three strongly worded orations by Demosthenes, had refused. Athens and Macedon signed a peace agreement (the Peace of Philocrates) in 346 B.C., and Demosthenes was one of the negotiators. Also representing Athens was a man Aeschines. During the negotiations, Philip ignored Demosthenes and focused his attention on Aeschines; this was the start of a decades-long enmity between the two Athenians. Demosthenes returned to Athens and addressed the Assembly, in a speech titled "On the Peace," warning that Philip was not to be trusted, no matter how many peace treaties he signed. In 344 B.C., Demosthenes delivered the Second Philippic, highlighting Macedon's recent warlike activity against Sparta and Thebes. The Third Philippic came in 341 B.C. and resulted in Demosthenes' being granted control of the navy and architect of a grand alliance against Philip. The coalition was no match for Philip and the vaunted Macedonian phalanx, however, and the result was a massive Macedonian victory in 338 B.C., at the Battle of Chaeronea. Leading the charge and helping to secure victory in this pivotal battle was Philip's famous son Alexander. When Philip died in mysterious circumstances in 336 B.C., Alexander took over the reigns in Macedon and continued his father's work, both in subjugating the Greek city-states and in preparing for war against Persia. Again and again, Macedon was victorious. At one point, Alexander demanded the surrender of Demosthenes and other famous Athenians who had proved implacable; a special negotiator from Athens succeeded in rescinding that command, and Demosthenes, Aeschines, and others lived to see another day.

Demosthenes' most famous speech is possibly "On the Crown, which he delivered in 330 B.C. He finally succeeded in prosecuting his longtime antagonist Aeschines, who was convicted of crimes against the state and forced into exile. Ironically, Demosthenes himself was found guilty of a crime against the state six years later and thrown into prison. When Alexander the Great died in 323 B.C., Athens recalled Demosthenes from exile. His homecoming was short-lived, however, when Alexander's successor, Antipater, arrived with an army of occupation and called for the people of Athens to sentence Demosthenes to death. Rather than face the prospect of such a conviction, Demosthenes fled and, facing capture in Caluria, administered his own death, by way of poison, in 322 B.C. Demosthenes is thought to have married and had a child, a daughter. Historians disagree on both of those points. The influence of Demosthenes and his oratory and logography is long and wide. A few hundred years later, when the Roman orator Cicero got up in the Senate and delivered a series of speeches opposing Marc Antony, the Romans referred to Cicero's speeches as Philippics. Romans learning oratory studied the speeches of Demosthenes. Partly because of the efforts of the Library of Alexandria and of subsequent scribes and scholars, more than 60 speeches given and/or written by Demosthenes survive.

|

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White