Athens: Ancient Greece's Guiding Light, Dark Warning

Part 1: Beginnings and Government Most sources say that Athens was settled as long ago as 5000 B.C. The settlement wasn't overflowing with rich agricultural land, but it did have several hills and was close to the sea. Very early on, Athens emerged as a maritime power. The settlement was on Mount Lycabettus, between a handful of rivers: the Cephissus, the Eridanos (which flowed through the settlement), and the Ilissos. Walls surrounded the city proper, which was just less than a mile in diameter.

Dominating the city skyline was the Acropolis, a large steep rock on which sat the famed temple the Parthenon, the temple complex Erechtheion, the Temple of Athena Nike, and a number of statues and other works of art. The largest and most famous of those statues was the Athena Promachos, a huge depiction of the city's patron goddess, dressed for battle. Other hills dotted the landscape, among them the Areopagus and the Pynx. The lower city was called the Agora, a large open space that housed many buildings of different purposes; among those were a mint, a library, a few theaters (the most famous of which was the Theater of Dionysus), odeaons (housing musical contests), and several temples and monuments and altars. Additional to the buildings were stoae, covered walkways that featured columns and lined the side of buildings. Punctuating the walls that surrounded the city were several gates; two of the more famous of these were the Sacred Gate and the Gate of the Dead. Suburbs stretched out around the city proper. In addition, the city of Athens was connected to the port city of Piraeus by the Long Walls, a pair of 4.5-mile-long wooden walls with a narrow passage in between them. Other city-states, notably Corinth, had Long Walls; the ones in Athens were the most famous. Athens was known far and wide for its population's propensity to take part in civic life. The word idiot comes from the idea of a person's not participating in public affairs. Athenians were often to be found out of doors, speaking with others–discussing, debating, creating, exercising, learning. GOVERNMENT

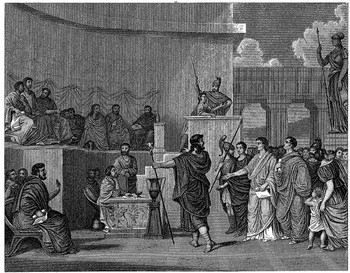

The government of Athens has become known as a democracy, and it certainly was; however, it was more than that and, conversely, not always that. The word democracy comes from the Greek words demos (the entire group of citizens) and kratos (rule). The key word in the concept is citizen. This was not everyone living in Athens. The number of citizens living in the city-state at the time of its greatest prominence, in the 5th and 4th Centuries B.C., was as many as 60,000. The total population was much larger than that. Citizens had to be male and 18 or older. Slaves could not take part; neither could women; neither could resident foreigners. Many estimates put the percentage of citizens in the population at no more than 30 percent. The main body of government was the Ecclesia, or Assembly, which met at least once a month and sometimes two to four times a month. The Assembly met on the Pnyx hill, at a space set aside for the purpose; the space could hold about 6,000 people. The Assembly typically discussed things like treaties, expenditures, food supplies, foreign affairs, and military matters. Any member of the Assembly could speak to the group as a whole. Any proposals put to the Assembly were voted on by all members present, by means of a raised hand; the majority won, and the decision was final. Another kind of vote sometimes exercised by the Assembly was ostracism, a separate process that took place outside normal Assembly meetings. Ostracism involved writing onto a piece of broken pottery (the equivalent of scrap paper) the name of someone they thought had become too powerful or was endangering the city-state. (Some Assembly members were illiterate; in this case, a scribe would write the name for them. The person whose name appeared on the most pottery shards would be ostracised. (It had to be a sufficiently large number, though; most sources say that it had to be at least 6,000.) A person marked for ostracism was banished from the city-state for 10 years; he had 10 days to leave. Once the 10 years were up, he could return and continue as before; his status and property were not diminished while he was gone. Another governmental body in Athens was the boule, a group of 400 to 500 citizens chosen by lot to serve for one year. The boule played a part in deciding what was discussed in meetings of the Assembly and also served as finance directors and military advisers. A subgroup of the boule was an executive committee known as the prytaneis who were elected on a rotating basis; the chairman of the prytanei was the epistates, and the holder of that position rotated among the committee. Laws or decrees made by the Assembly could be challenged in the courts, which were made up of the chief magistrates, the archons (chosen annually by lot), and the courts, which had up to 6,000 jurors; the holders of all of these positions had to be 30 or older. Private lawsuits went before a jury that had a minimum size of 200. Public lawsuits went before a jury that had a minimum size of 501. During a trial, the prosecutor and the defendant each spoke for up to three hours, with their speaking time marked by a clepsydra, or water clock. Jury deliberations were unusual; most commonly, jurors voted straight away, in keeping with the idea that trials should take no longer than a day. Jurors were not paid initially but were eventually paid a minimal fee.

The chief magistrates of Athens for a time were the Archons. They were three members of the aristocracy elected to 10-year terms. One was the head of the armed forces, one was the head of religious festivals and cultural festivals, and one was the overall head of the judicial system. The terms of service were later shortened to one year. Also of note in Athenian governmental circles was the Areopagus, a council of elders that was a model for the Roman Senate. Only those who had already held public office (in practice, meaning only Archons) could be a member of the Areopagus. This tribunal served as a sort of high court under the democracy in Athens, trying cases of homicide, assault, and other serious crimes. Occasionally, the Areopagus would hear cases of alleged sacrilege. Those convicted by the Areopagus most often faced exile and confiscation of property. Next page > Arts&Culture and Wars > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White