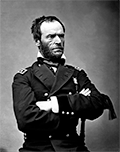

Union General William Tecumseh Sherman

William T. Sherman was a Union general during the American Civil War. He is most well-known for his capture of Atlanta and his devastating "March to the Sea." He was born on Feb. 8, 1820, in Lancaster, Ohio. His father, Charles, died when the boy was young, and William grew up in the home of a family friend, the attorney Thomas Ewing. William's middle name was Tecumseh, a name that his father chose because he was inspired by the Shawnee leader.

Sherman entered the U.S. Military Academy when he was 16. Graduating four years later, he went straight into combat, in the Second Seminole War. He was stationed in California during the Mexican-American War. In 1850, he married Eleanor Boyle Ewing; they had eight children. He was a bank manager in San Francisco, practiced law in Kansas, and managed a street car company in St. Louis. In 1859, he served as the first superintendent of Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy; he was also a professor, teaching architecture, drawing, and engineering. Sherman had the rank of colonel when the Civil War began. He resigned from his job in Louisiana and moved to the North. He was on the battlefield for the resounding Confederate success at the First Battle of Bull Run. Promoted to the rank of brigadier general, Sherman found himself assigned to take command of the Department of the Cumberland, in the Western Theater. After a brief stint in that job, he joined the command of Ulysses S. Grant. Sherman commanded troops at Shiloh (during which he sustained two minor wounds and had three horses shot from under him and after which he was promoted to major general), Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. After that last battle, Grant went east to take over command of all Union armies and Sherman, promoted to brigadier general, took over command of the Military Division of Mississippi. In that capacity, he set out to take Atlanta. Engaging in a series of counter-and-thrust maneuvers with the Army of Tennessee under Gen. Joseph Johnston, Sherman and his men pivoted their way ever southward, engaging in a few skirmishes along the way as they edged through northern Georgia. The one exception to this was the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, in which Sherman ordered a frontal assault against a well-dug-in opponent and lost 3,000 men (to 1,000 Confederate casualties). Johnston and his forces eventually ran out of resistance and geography; and on Sept. 2, 1864, Sherman and his army captured Atlanta.

Sherman's men had begun their trek in Jackson, a city that they burned nearly to the ground. They continued a moderate sort of scorched-earth policy as they marched to the southeast. When they captured Atlanta, they burned it as well. The goal was to destroy the Confederacy's ability to make war, so Sherman's men burned not only military facilities but also homes and businesses. They did more of the same as they marched from Atlanta to Savannah, on the Atlantic Coast, in what came to be known as "Sherman's March to the Sea." The army 60,000 strong abandoned their supply lines and lived off the land, seized food and property as they saw fit, illustrating Sherman's famous quote: "War is hell." They destroyed railroads (which became known as "Sherman's neckties"), buildings, and farms, as they made their way 300 miles to the coast. On Dec. 21, 1864, Sherman and his troops seized Savannah. Turning north, Sherman and his men continued their devastation, up into South Carolina and then in North Carolina, laying waste to the countryside and several cities as they went. They fought against Joseph Johnston's troops at Bentonville, N.C., on March 19–21, 1865. Not long after that battle, both commanders received word of the surrender of Robert E. Lee to Grant at Appomattox. Sherman and Johnston met and agreed on terms, and Sherman accepted the surrender of more than 90,000 men on April 26. Sherman made sure that the captured men got 10 days of rations, for which Johnston and his men were grateful. Sherman retained his Army commission after the war and commanded the Military Divisions of Mississippi and Missouri. Grant was elected President in 1868, and Sherman succeeded him as commanding general of the U.S. Army. He had that role until 1883, overseeing the Army's dealings with native Americans in the West. He published his memoirs, with the title of the same name, in 1875. He died on Feb. 14, 1891, in New York City. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White