The Union Army's 'March to the Sea'

The Union Army's "March to the Sea" in late 1864 destroyed a large amount of Southern infrastructure and also sapped Confederate morale. For five weeks in November and December 1864, the troops under Union Gen. William T. Sherman personified their commander's maxim that "war is hell" by devastating the Georgia countryside, in an effort to sap the morale of the Confederate troops and populace.

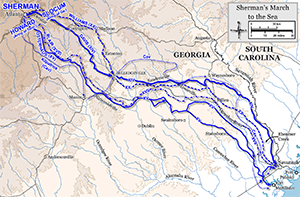

Sherman (left) had struck a symbolic blow on September 2 by capturing Atlanta, defeating a pair of well-known Confederate commanders, Joseph Johnston and John Bell Hood, in the process. Neither Johnston's defensive tactics nor Hood's aggression seemed to faze Sherman and his Army of the Tennessee, as they steadily wore down and defeated the armies in their path. Adding the Army of Georgia to the mix, Sherman and company set off from Atlanta on Nov. 15, 1864, with 62,000 men. They ignored a western feint by Hood, designed to draw them back into Tennessee, and headed for the Atlantic Ocean. Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. George Thomas and the Armies of the Cumberland and the Ohio were running interference, preventing whatever was left of Hood's army from striking at the rear of Sherman's overland invasion force.

Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard led the Army of the Tennessee toward Macon. Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum led the Army of Georgia toward Milledgeville, at the time the state capital. The two armies ranged a few dozen miles apart. Opposing the march of all of those Union troops were 13,000 Confederate soldiers under Lt. Gen. William Hardee. Both segments of Sherman's overall army laid waste to the countryside for 300 miles, destroying farms, manufacturing plants, and railroads as they saw fit. They ripped the rails off the tracks, heated them up, and then twisted them around trees; these wrecked hunks of metal came to be known as "Sherman's Neckties." Union and Confederate troops fought against each other, as Hardee tried to stop Sherman's advance. A battle at Griswoldville on November 22 resulted in a strong Union victory. Subsequent skirmishes had the same result. One bright spot for the Confederate command was came on November 30, a stiff defense of entrenchments at Honey Hill.

Hardee and his men got to Savannah first, having practiced somewhat of a "scorched earth" policy as they traveled, and erected a series of defenses, including the flooding of the fields around the city. Sherman responded by linking up with U.S. Navy ships off the coast and making plans to settle in for a siege. On December 17, Sherman announced plans to begin a large-scale bombardment if Hardee did not surrender. Sherman waited a few days, hopeful of being able to take the city peacefully. Hardee and his men escaped on December 20; and the next day, Union troops seized the city. Sherman's "March to the Sea" was a strong blow to the South's morale, demonstrating that its army could do little to protect against such wholesale destruction. Sherman's army didn't burn cities but did wreck buildings and other elements of the war effort. They also ranged far and wide through the countryside, foraging for food and water because they had left their supply lines behind, determined to "live off the land." The capture of Savannah, coupled with the loss of Atlanta (which did burn, quite badly), made many in the South doubt that their Confederacy had much time left. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White