Virgil "Gus" Grissom was a former military test pilot and astronaut who was in the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs.

He was born on April 3, 1926, in Mitchell, Ind. He worked odd jobs as he was going through school and graduated from Mitchell High School in 1940. Another he did while growing up was develop an interest in flying. A friend taught him how to fly a plane. In 1943, Grissom enlisted in the U.S. Army Forces. He train in Texas and was then assigned to Boca Raton Army Airfield. He left the military after the end of World War II and went to work at a factory that made buses. He enrolled at Purdue University in 1946 and graduated in 1950 with a bachelor of science in mechanical engineering. He was back in the military after that, this time with the newly formed U.S. Air Force Base. He earned his pilot's wings in 1951 and saw combat in 1952, flying 100 combat missions during the Korean War. Returning to the U.S., he served as a flight instructor at a Texas Air Force base and then moved to the Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright-Pattern AFB, from which he earned a bachelor of science degree in aeromechanics. He completed test pilot training at California's Edwards Air Force Base.

In 1959, Grissom was invited to apply for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) astronaut program. He was accepted and then was named as part of the "Mercury Seven," the astronauts who flew into space as part of Project Mercury. He flew aboard Liberty Bell 7 on July 21, 1961; it was the second Mercury flight, following Alan Shepard's historic flight. Three years later, Grissom became the first astronaut to fly into space twice, as commander of Gemini 3 (along with John Young. His last Gemini assignment was as backup command pilot for Gemini 6A.

He was named to the crew of the first three-man mission, which began its life as AS-204 and later became Apollo 1. Grissom (right, left) was named the Command Pilot. Another Gemini veteran Ed White, (right, center) as Senior Pilot, and rookie Donn Eisele as Pilot. Gemini communications veteran Roger Chaffee (right, right) replaced Eisele when the latter dislocated his shoulder during weightlessness training. The launch date was Feb. 21, 1967. The target time for the mission was two weeks.

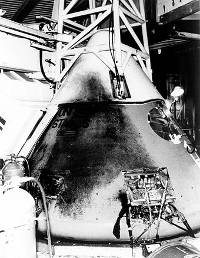

The incident that claimed Grissom's life occurred on January 27, a little more than three weeks before launch. It was just an exercise, a "plugs-out" test, a run-through for the spacecraft with all of the cables and umbilicals removed. The test was not a new thing: Scientists had performed numerous such tests for both Mercury and Gemini. The "plugs-out" test was classified as nonhazardous the spacecraft had no fuel or cryogenics in it. Further, any explosive bolts had been removed. Inside the command module, the atmosphere was 100 percent oxygen. Some scientists had suggested that the atmosphere be a mix of nitrogen and oxygen, much as the air that people breathe every day. However, fresh in the minds of organizers was the experience of test pilot G.B. North, who, while testing a Mercury atmosphere system, had gone unconscious and seriously hurt himself because the atmosphere was too high in nitrogen. As well, thinking ahead to the Moon, NASA wanted to streamline the breathing protocol of the astronauts with regard to their spacesuits, and a pure oxygen atmosphere made this process faster than did a nitrogen-oxygen mix. The Apollo spacecraft had in its design a target pressure of 5 psi (pressure per square inch), the same as that in space. The test was conducted not in space but on the ground, where pressure starts at 14.7 psi. Scientists cranked the pressure up even further for the test, to 16.7 psi. The downside of that pressure level was that it made clothing and metals highly prone to catching fire and burning. The hatch was designed to be opened slowly and by hand. Designers were mindful of the hatch door of Grissom's Project Mercury flight, which had opened on its own, putting the astronaut in jeopardy. The door was designed for the pressure inside the capsule to be higher than the pressure outside and for the astronauts, should they need to open the hatch, to overcome that pressure disparity by accessing a valve that would vent the inside pressure. The test had begun at 1 p.m. Grissom had complained of a strange small after he had hooked up his oxygen supply; no one could explain the cause of the smell, and preparations continued. In a related problem, the high flow of oxygen more than once set off the master alarm. No one was able to solve the problem and nothing really seemed to be the matter, so NASA and the astronauts decided to ignore the alarm. Problems with communications systems dogged the first few hours of testing. At 5:40 p.m., NASA officials called a timeout in a last attempt to sort out the comm system.

At 6:31 p.m., fire broke out inside the capsule. All three astronauts succumbed to smoke inhalation and passed out; they died in the fire, largely because of high concentrations of carbon monoxide, the results of the blaze. The pressure level in the capsule had effectively sealed the door shut; as well, the valve that astronauts were to use to vent that inside pressure was obscured by white-hot flames. The oxygen-rich fire had increased the pressure to 29 psi, shattering the inner wall of the capsule. The fire was in danger of spreading upwards, to the launch escape system and then to the whole structure on top. Because the test was deemed nonhazardous, a contingent of fire, rescue, and medical teams was not standing by. A host of firefighters who had been quickly mobilized and who raced to the scene did what they could, but it was too late. They did succeed in containing the fire. Chafee, Grissom, and White were mourned nationwide. Grissom is remembered in the names of schools and other buildings, museums, and an air force base. He married Betty Moore in 1945. They had two children. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White