The Battle of the Wilderness

The Battle of the Wilderness was an inconclusive clash between Union and Confederate troops during the American Civil War. It was the first battle in the Overland Campaign, which eventually led to the surrender of Confederate troops in April 1865. In March 1864, President Abraham Lincoln named Ulysses S. Grant general-in-chief of all Union armies. Frustrated by a serious of generals and commanders who preferred caution to aggression, Lincoln had The specifics of the plan to attack Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia were threefold:

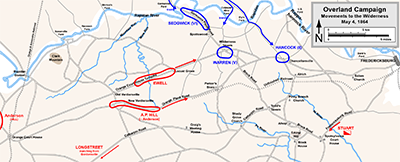

Union troops under Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock began crossing the Rapidan on May 4 and reached Chancellorsville at midday. At the same time, men under Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick and Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren, using pontoon bridges, crossed the river at Germanna Ford. Warren's men were the first to cross and reached Wilderness Tavern, where they stopped. Sedgwick's men populated the road between the tavern and the ford. Grant was waiting for another corps, led by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, to reinforce from the west. They had not arrived by nightfall on May 4. As dusk fell, the Union troops camped in the Wilderness of Spotsylvania, a large overgrown forest. Such a location would negate the large numbers of men and weapons that the Union could bring to bear should it be attacked. All told, Union troops in the area exceeded 100,000. As so often happened during the Civil War, Lee knew the whereabouts of the Union army. The veteran Confederate commander sent his troops numbering 65,000 east on the double. They camped on the night of May 4 just three miles from the Union army. Lee had also sent word to Maj. Gen. James Longstreet to leave his position at Gordonsville and join Lee at the Wilderness. The next day, a Confederate contingent surprised a column of Union troops near a clearing known as Saunders Field. Grant, seeking to regain the initiative, ordered an attack right away. The attack came a few hours later, after the Union troops had prepared fully for the assault. (Having Grant, who favored quick action, in charge was a change for the men of the Army of the Potomac, who were used to men like George McClellan, who moved slowly and carefully.) The Union troops did finally attack, and the fighting was desperate and confused.

Brambles and branches, roots and stumps stood in the way of both armies as they struggled for purchase in the dense aptly named Wilderness. The smoke from weapons discharges stayed within the umbrella of trees, creating an unnatural fog into which few could see clearly. Friendly fire injuries were rife, as were shots fired at nothing at all. Confederate troops under A.P. Hill looked to be having the better of the fight in midafternoon, but the arrival of Sedgwick's troops into the fray prevented any advantage. The arrival of Burnside's troops buoyed Union hopes. Darkness stilled the guns. On the following day, May 6, Union troops attacked at first light. Their superior numbers pushed Hill's men back nearly to Lee's headquarters, at Widow Tapp Farm. With their backs against the wall, the Confederates could only hope that Longstreet and his men would arrive. They finally did, jumping into the fight with a furious counterattack along the Brock Road line that, along with another counterattack by troops under Gen. John Gregg, forced the Union troops to give ground. A number of Confederate troops discovered that an unfinished railroad grade gave them excellent cover from which to fire indiscriminately at soldiers dressed in blue. Lee ordered another attack late in the day that gained no purchase. The only Confederate success on the day, other than repulsing the Union advance, was to exploit a weakness on Sedgwick's right flank. Union troops there gave way and were saved from further retreating action by darkness. Many soldiers who fell wounded were still on the battlefield that night. A brush fire between the two armies burned many of the wounded. The number of dead swelled. In the morning, Grant ordered his troops to move out. They had orders to move forward, to the south, not back north or back east or west. Unlike after previous battles, the Army of the Potomac did not retreat; rather, they continued on their march south, to Richmond. Union casualties numbered 17, 666 (2,246 dead, 12,037 injured, 3,383 captured or missing); Confederate casualties totaled 11,033 (1,477 dead, 7,866 injured, 1,690 captured or missing). One of those wounded was Longstreet, who, like Stonewall Jackson before him, was hit by friendly fire. Longstreet recovered five months later. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White

been impressed with Grant's actions in the West, particularly in directing the July 1863 victory at

been impressed with Grant's actions in the West, particularly in directing the July 1863 victory at