|

Re-enacting America's Largest Slave Uprising

November 9, 2019

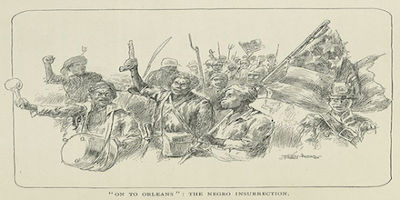

Retracing the route taken by the 19th-Century slaves, the volunteers chanted "Freedom or Death" and other inspirational slogans as they walked along a levee on a two-day, 26-mile journey that began near La Place and ended in New Orleans. This time around, the idea was to celebrate the people who risked their lives in a desperate bid for freedom. Capping the journey was a celebration in New Orleans' Congo Square, in Louis Armstrong Park. Leading the re-enactment was a New York-based artist named Dread Scott (an echo of the famous slave whose lawsuit reached the U.S. Supreme Court). The artist, whose real name is Scott Tyler, gained prominence in 1989 with a controversial art exhibit focusing on ways to display the American flag. He is known for art works in several media, including painting, photography, and performance art. Among those documenting the experience was John Akomfrah, a Ghanaian-British filmmaker and writer who for many years has chronicled the experiences of immigrants worldwide and the challenges that nature faces in the wake of interactions with people. Known as the German Coast Slave Revolt, the four-day uprising involved up to 500 slaves who were willing to take extreme action to gain their freedom. The uprising flared in Jan. 8–11, 1811, in what is now Louisiana. The German Coast was a group of settlements north of New Orleans, along the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. The area got its name from the large number of German-speaking people who had settled there beginning in the 1720s. As with many other parts of Louisiana and other Southern states, this area was home to plantations, particularly those that deployed slaves to the backbreaking work of cutting and harvesting sugar cane. The violent part of the uprising began on Jan. 8, 1811, at the plantation of Manuel Andry. Charles Deslondes, a slave driver of mixed racial descent, led a band of two dozen slaves in an attack on the plantation owner. Andry was severely injured but survived; his son, Gilbert, did not. In the subsequent plunder of the plantation, some of the slaves took Andry's militia uniforms and later wore them. (The slaves who rose up in revolt in Haiti had done a similar thing. In another connection with that uprising, Deslondes was originally from Haiti.) The attackers had wielded axes, hoes, clubs, and cane knives–the tools with which they did their backbreaking work. They took as well from the Andry storehouse a few guns and some ammunition. Then, they set out for New Orleans, with the hope that they could repeat the success of those enslaved in Haiti, who had rise up en masse and used their superior numbers to overwhelm the slave owners and declare the first black republic in the world in 1804. It was a two-day trek on foot. Along the way, the number of those rising up swelled, as more and more slaves helped Deslondes and his original group burn plantations and take what they could find along the way, killing two plantation owners in the process. Estimates are that up to 500 slaves joined the uprising. They did want to make it to New Orleans, but they also wanted to ultimately establish their own self-governed territory somewhere along the banks of the Mississippi River. On January 11, the uprising ended, with a firefight. Some slaves were veterans of civil wars in Africa, but the majority were not trained in any kind of combat. The number of guns that they held was very small. The result was the deaths of several dozen slaves and the capture of the rest.

|

Social Studies for Kids |

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White

A group of determined volunteers donned period clothing, some marched and others rode horses, and all got into the spirit of historical re-enactment as about 500 people commemorated America's largest slave uprising with a 26-day march.

A group of determined volunteers donned period clothing, some marched and others rode horses, and all got into the spirit of historical re-enactment as about 500 people commemorated America's largest slave uprising with a 26-day march.