The German Coast Slave Revolt

The German Coast slave revolt was the largest slave uprising in American history. Up to 500 slaves took part in a march to what they hoped was freedom in New Orleans in 1811. The United States had gained the area and a much larger amount of land in the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. In the ensuing months and years, the Territory of Orleans took shape. The German Coast was a group of settlements north of New Orleans, along the eastern bank of the Mississippi River. The area got its name from the large number of German-speaking people who had settled there beginning in the 1720s. As with many other parts of Louisiana and other Southern states, this area was home to plantations, particularly those that deployed slaves to the backbreaking work of cutting and harvesting sugar cane.

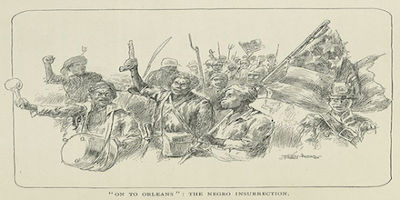

The violent part of the uprising began on Jan. 8, 1811, at the plantation of Manuel Andry. Charles Deslondes (left), a slave driver of mixed racial descent, led a band of two dozen slaves in an attack on the plantation owner. Andry was severely injured but survived; his son, Gilbert, did not. In the subsequent plunder of the plantation, some of the slaves took Andry's militia uniforms and later wore them. (The slaves who rose up in revolt in Haiti had done a similar thing. In another connection with that uprising, Deslondes was originally from Haiti.) The attackers had wielded axes, hoes, clubs, and cane knives–the tools with which they did their backbreaking work. They took as well from the Andry storehouse a few guns and some ammunition. Then, they set out for New Orleans, with the hope that they could repeat the success of those enslaved in Haiti, who had rise up en masse and used their superior numbers to overwhelm the slave owners and declare the first black republic in the world in 1804.

It was a two-day trek on foot. Along the way, the number of those rising up swelled, as more and more slaves helped Deslondes and his original group burn plantations and take what they could find along the way, killing two plantation owners in the process. Estimates are that up to 500 slaves joined the uprising. They did want to make it to New Orleans, but they also wanted to ultimately establish their own self-governed territory somewhere along the banks of the Mississippi River. The timing of the uprising was not an accident. The sugar harvesting and processing had been done, and many slave owners had cut back on the demands of their slaves. As well, the garrison charged with protecting New Orleans was at the time in West Florida, cementing the takeover of that piece of land. Nonetheless, the number of available federal troops was more than enough to stop the slaves from reaching their destination. Orleans Territory Gov. William Claiborne called out a group of local militia. That group met up with another, from Baton Rouge, 16 miles from New Orleans. Also with them was Manuel Andry, on whose plantation the uprising had begun. On January 11, the uprising ended, with a firefight. Some slaves were veterans of civil wars in Africa, but the majority were not trained in any kind of combat. The number of guns that they held was very small. The result was the deaths of several dozen slaves and the capture of the rest. The militia reported no deaths on its side. Three days later, a local tribunal sentenced the leaders of uprising to death–some by firing squad, others by more grisly methods. Officials displayed the heads of some of the leaders, like Deslondes, on poles and spikes, as a warning to anyone who contemplated taking up a similar cause. The federal government also increased the numbers of federal garrisons in Orleans and in the surrounding states. The German Coast uprising was an example of how a determined group of slaves could conduct an organized resistance against the brutalities of slavery. As with other more well-known uprisings (such as the one led two decades later by Nat Turner), this set of actions helped to dispel the myth perpetuated by many slaveowners that slaves were happy with their lot in life. It was also an example of the lengths to which slaveowners would go to keep their "possessions." New Orleans became a state in 1812, the same year that the United States went to war again with Great Britain. American troops in the South paid particular attention to British maneuvers in the area, mindful of another uprising by the New Orleans enslaved population. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2026

David White