The Achievement of Women's Suffrage in the United Kingdom

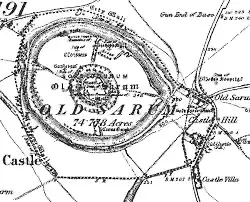

Part 1: The Lay of the Land Women in the United Kingdom first got the vote in 1918. It was a long, difficult struggle achieved at great cost. From the time of the first parliament in 1265, the members of that body have been elected by citizens of the realm. At that time and for long afterward, the number of people who could vote was very small and the parliaments of the day didn't meet very often. Henry VI in 1432 enacted a statute setting qualifications for voting: Only those who owned property worth 40 or more shillings could vote. In those days, that was quite a lot of money, so the number of people who could vote was still quite small.

It wasn't until 1832, nearly 600 years after the formation of the first parliament, that that body of elected officials increased in a meaningful way the number of people who could select the members of that parliament. The Reform Act 1832 had expanded the voter rolls by a few hundred thousand, but the number of people who could vote was still a small minority of the overall population. The Reform Act 1867 had added 1.5 million more men to the voter rolls, but it was still only one-third of all eligible males in the population. And it was during debate over this, the Second Reform Bill, that philosopher and Member of Parliament (MP) John Stuart Mill first proposed the idea of granting women the vote. Women were not up to this time legally prohibited from voting. However, the customs of the time did not allow women many privileges. Some women owned property, but they didn't seem to be the ones who wanted to run for elective office. By and large, the existing statutes and customs were enough to keep women from voting. Mill's amendment to the Second Reform Bill went down to resounding defeat, opposed in great fashion by then-Prime Minister William Gladstone inside Parliament and Queen Victoria outside Parliament. In fact, the wording of the bill that eventually passed specifically defined an eligible voter as "male."

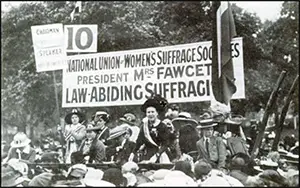

The drive toward achieving women's suffrage included many different people and groups who employed varied strategies to make their case that they deserved the legal right to vote just as much as men did. Early in the 19th Century, some in Parliament were discussing extending the right to vote to more members of the working class and to women. Women were not members of Parliament, of course, and so had to rely on men to advance their case within the halls of government. Out in the streets of cities and towns, however, women gathered in groups to make speeches; march holding signs of advocacy and protest; and writing and publish leaflets, pamphlets, newspapers, and books detailing the unfairness of their being denied the vote. One of the first groups of women to gather with the express purpose of advancing that cause was the Kensington Society, formed in 1865 by Charlotte Manning. Eleven women in all were in the initial gathering; the number of members soon swelled to several dozen. More women gathered to spread the word, and more groups formed, in London and elsewhere. A Third Reform Act in 1884 extended the rights of male voters to those living in rural areas but did nothing of the kind for women. Next page > Laws on the Books > Page 1, 2 |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White